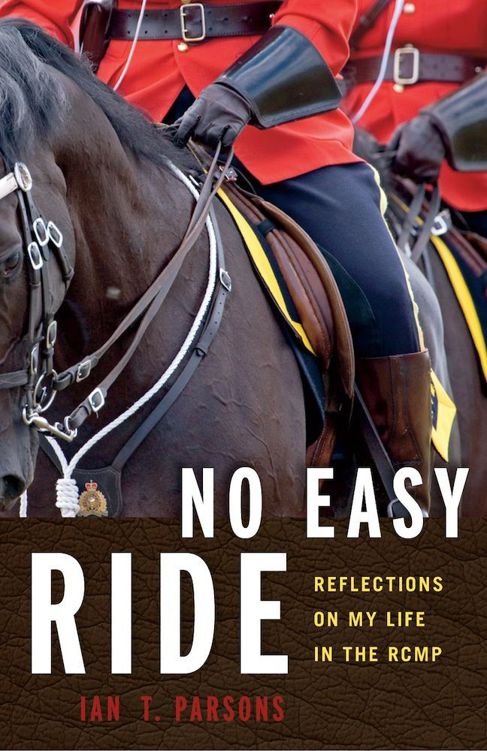

No Easy Ride: Reflections on My Life in the RCMP

Read No Easy Ride: Reflections on My Life in the RCMP Online

Authors: Ian Parsons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Law Enforcement, #BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Law Enforcement

On July 3, 1961, Ian Parsons reported to RCMP Depot Division in Regina as a raw recruit. It was the beginning of a 33-year adventure that took him from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island and many points between. By the time he retired with the rank of inspector, Parsons had a policeman’s trunk full of colourful stories and insightful observations that he now shares in this memoir.

Parsons writes candidly of his many roles within the RCMP, from postings in rural detachments, where he dealt with diverse policing issues, to stints teaching at the Canadian Police College in Ottawa and at the RCMP Academy in Regina. Always an independent thinker, Parsons lectured sometimes-resistant RCMP senior officers on the adoption of new ways and helped introduce programs to modernize recruit training and make it more relevant to the demands of a rapidly changing Canadian society.

In recent years, Parsons has observed the troubled state and tarnished reputation of his beloved force as it faces crisis after crisis. Against the entertaining backdrop of his life in red serge, he gives a thoughtful assessment of things gone wrong in the iconic institution and identifies the drastic steps necessary to save it.

“I can only imagine a few people who could share the experiences as well as Ian Parsons.

No Easy Ride

leaves nothing to the imagination about where the force has come from and where it should be going.”

—Morley Lymburner,

Blue Line magazine

“Ian Parson’s highly readable memoir casts an insightful eye on issues in the iconic federal force. His conjecture on the future of the RCMP merits thoughtful consideration by all Canadians.”

—Robert F. Lunney, Chief of Police (Ret.), author of

Parting Shots

RIDE

REFLECTIONS

ON MY LIFE

IN THE RCMP

IAN T. PARSONS

Dedicated to the two most

important women in my life:

my wife, Lynne, and my daughter, Michelle.

The world is a better place for your intellect,

compassion and common sense.

Also to my mother, Patricia Parsons,

who devoted 60 years to supporting

her husband and her son in their

RCMP careers. She passed away in

October 2012 in her 102nd year.

| | PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD |

| | PREFACE |

| CHAPTER 1 | THE WAY IT WAS |

| CHAPTER 2 | STAND STILL, LOOK TO YOUR FRONT |

| CHAPTER 3 | RIDE, TROT! |

| CHAPTER 4 | WELCOME TO THE FIELD |

| CHAPTER 5 | TEMPORARY POSTINGS, TEMPORARY TRAUMA |

| CHAPTER 6 | PRAIRIE ROOTS |

| CHAPTER 7 | DO AS I SAY, NOT AS I DO |

| CHAPTER 8 | FLAILING AT WINDMILLS |

| CHAPTER 9 | CULTURAL IMMERSION AND SWEETGRASS |

| CHAPTER 10 | PUZZLE PALACE AND BEYOND |

| CHAPTER 11 | DÉJÀ VU |

| CHAPTER 12 | AN OFFICER AND A GENTLEMAN? |

| CHAPTER 13 | HALFWAY HOME |

| CHAPTER 14 | HOME AT LAST |

| CONCLUSION | END OF A DYNASTY? |

| | PHOTO INSERT |

| | ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS |

IT HAS LONG

been the legacy and legend of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Canada’s national police force, that they could overcome any obstacle when asked to do too much with too little. It was a cherished reputation built over a century of policing new frontiers, at first across the Canadian prairie and later over the 3,000 miles from Vancouver Island to Newfoundland. These brave men usually functioned alone, remote from media scrutiny and without the many complexities of modern times. Through real deeds and, later, Hollywood portrayals, the police force established an image that became an internationally recognized symbol of Canadian society and justice. Today, maintaining that reputation is proving burdensome.

Canada’s parliament first passed a bill in 1873 to create the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) and establish a force of 300 scarlet-coated riders, sent west from Ontario with a mandate to bring law and order to the Dominion’s North-West Territories. Things started badly.

Most historians agree that the NWMP’s first commissioner was the wrong leader on the wrong trail with the wrong horses. During the 10 weeks after disembarking the Red River camp at Fort Dufferin on July 8, 1874, Colonel George French failed dismally, forcing his ill-conceived strategy on what started as six divisions of 50 mounted policemen. Even as they broke camp that day, two of French’s division leaders resigned in total frustration, angered that their commissioner insisted on using his regal hand-picked eastern steeds instead of trained cart horses readily available at the fort.

Within 60 days, almost three-quarters of French’s herd of matching bays, light bays, chestnuts, blacks, browns and greys were either dead or lame. Supplies had dwindled, morale was on its own death march and they were effectively lost. The threat of early snow and even starvation hung over the camp as French and his assistant commissioner, James Macleod, headed south into Montana in search of supplies and a good scout.

Fortunately the weather held and supplies were secured, and as a blessing to all, George French was summoned east by his superiors. With the well-respected Macleod left in charge and their new scout, Jerry Potts, at the front of their column, the NWMP headed farther west to build their first fort and establish a foothold for law and order on the Canadian prairie at Fort Macleod.

In contrast to the bloodletting that occurred on American soil, the NWMP gained the trust of tribal leaders and maintained peace through their first decade in the West. In 1886, after the Metis rebellion, there were 1,000 men enlisted, and the achievements of James Macleod, Sam Steele, James Walsh, Cecil Denny, other NWMP original recruits and Jerry Potts are now well documented.

In spite of their heroics, the Mounties’ existence was threatened in 1896 when Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier announced his intent to disband the NWMP. A strong protest from the West and the beginnings of the chaotic Klondike gold rush assured the survival of the Force and its expansion into the Yukon. There, in gold camps north of Whitehorse, tiny detachments kept law and order, as they had done when small patrols had chased off Montana whisky traders, ridden in peace among the villages of the Blackfoot Confederacy, greeted the arrival of Sitting Bull and his followers as he crossed the Medicine Line, maintained peace as gangs of navvies built the rail lines to the mountains and protected ranchers and settlers as they set out to tame a raw landscape.

The NWMP became the Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP) by a proclamation of King Edward VII in 1904. When the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were formed the following year, the RNWMP continued to maintain both provincial law and federal law in the lands that were their first arena. That role continued until 1917, when both Saskatchewan and Alberta established their own provincial police forces, as British Columbia had done decades before. The following year the RNWMP was also assigned duties to handle federal laws in BC, a jurisdiction already well served provincially.

Even before there was a Canada, the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia shared early policing roots that dated back to the 1858 Fraser River and Cariboo gold rushes. When BC entered Confederation in 1871, the British Columbia Constabulary was formed. In 1895 the name was changed to the BC Provincial Police (BCPP). The BCPP would remain the prominent West Coast police presence through the Second World War and the early post-war years. At its peak, it was in charge of all rural areas plus 40 municipalities throughout the province.

Through the First World War, the RNWMP was largely confined to the Prairie provinces and Yukon Territory. East of Manitoba, federal policing had long been handled by the Dominion Police Force, a body originally formed five years before the NWMP to protect Ottawa politicians from assassination attempts. The Dominion force gradually expanded to administer federal laws, including a national fingerprint bureau and the parole service, and served as protector of naval dockyards at Halifax and Esquimalt, near Victoria, BC. It also assumed various policing duties in the Maritime provinces until the end of the Great War, when its contingent of almost 1,000 was briefly made a civilian arm of the Canadian Military Police Corps.

In 1920, the merging of the western-based RNWMP with the civilian corps of the Canadian Military Police Corps finally resulted in a truly national police force. The prominent red serge of the Mounties became the official uniform of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and the force was well on its way to building the most complex infrastructure of any police body in the world.

Establishing detachments in the High Arctic soon became a priority to protect Canadian sovereignty. By 1928, the Force had returned to handling Saskatchewan’s provincial laws under contract. Four years later, as the Depression stirred civilian unrest, members signed contracts with Manitoba and the three Maritime provinces to act as their provincial police as well. They also took over federal policing along Canada’s coastal perimeter while absorbing personnel and vessels from the Preventive Service of the Department of National Revenue. The essence of the RCMP Marine Section would be defined a decade later by Sergeant Henry Larsen, who captained the schooner

St. Roch

as it carved its way through the ice-laden Northwest Passage and became the first ship to ever circumnavigate North America.

In 1950, new layers of complexity were built into the RCMP when they were contracted as the provincial force in Canada’s newest province of Newfoundland, while absorbing the country’s oldest police roots when they integrated the BC Provincial Police into their structure. They were now the dominant municipal, provincial and federal police agency in Western Canada.

It was into this era of policing that Ian T. Parsons was born. His father, Joseph, had been a proud member of the RCMP since 1930. Ian enlisted while his father was still active in the Force, becoming part of a tandem that would serve their country for 64 consecutive years.

In the 33 years that Ian Parsons served, his assignments took him across the country from St. John’s, Newfoundland, to a final posting on Vancouver Island. He entered the Force while “old-school” training procedures were still in play. Later, as a new philosophy permeated the Force, he returned to teach at Regina in classrooms occupied by both men and women and enlistees representing many cultures. But Ian Parsons not only taught raw recruits in Regina; while stationed at headquarters in Ottawa, he also lectured the old guard of sometimes resistant RCMP senior officers on the adoption of new ways, new techniques and new social pressures of political correctness.