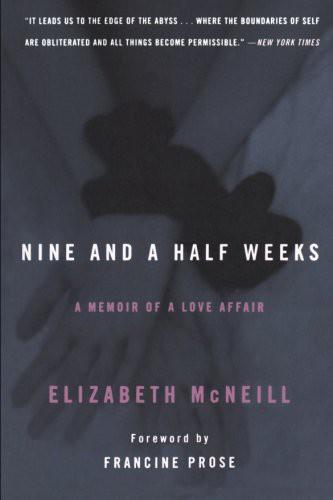

Nine & a Half Weeks

Read Nine & a Half Weeks Online

Authors: Elizabeth McNeill

9 1/2 Weeks

A Memoir of a Love Affair

By Elizabeth McNeill

THE FIRST TIME we were in bed together he held my hands pinned down above my head. I liked it. I liked him. He was moody in a way that struck me as romantic; he was funny, bright, interesting to talk to; and he gave me pleasure.

The second time he picked my scarf up off the floor where I had dropped it while getting undressed, smiled, and said, “Would you let me blindfold you?” No one had blindfolded me in bed before and I liked it. I liked him even better than the first night and later couldn’t stop smiling while brushing my teeth: I had found an extraordinarily skillful lover.

The third time he repeatedly brought me within a hairsbreadth of coming. When I was beside myself yet again and he stopped once more, I heard my voice, disembodied above the bed, pleading with him to continue. He obliged. I was beginning to fall in love.

The fourth time, when I was aroused enough to be fairly oblivious, he used the same scarf to tie my wrists together. That morning, he had sent thirteen roses to my office.

IT’S SUNDAY, toward the end of May. I’m spending the afternoon with a friend of mine who left the company I work for over a year ago. To our mutual surprise we’ve been seeing more of each other during the intervening months than while we worked in the same office. She lives downtown and there is a street fair in her neighborhood. We’ve been walking and stopping and talking and eating and she has bought a battered and very pretty silver pillbox at one of the stalls selling old clothes, old books, odds and ends labeled “antique,” and massive paintings of mournful women, acrylics encrusted at the corners of pink mouths.

I am trying to decide whether to backtrack half a block to the table where I’ve fingered a lace shawl that my friend has pronounced grubby. “It was grubby,” I say loudly to her back, a little ahead of me, hoping to be heard above the din. “But can’t you picture it washed and mended….” She looks back over her shoulder, cups her ear with her right hand, points at the woman in a very large man’s suit who is perusing a set of drums with ardor; rolls her eyes, turns away. “Washed and repaired,” I shout, “can’t you see it washed? I think I should go back and buy it, it’s got possibilities….” “Better do it, then,” says a voice close to my left ear, “and soon, too. Somebody else will have bought and washed it before she hears you in this noise.” I whisk around and give the man directly behind me an annoyed look, then face forward again and attempt to catch up with my friend. But I’m literally stuck. The mob has slowed down from a slow shuffle to no movement at all. Directly before me are three children under six, all with dripping Italian ices, the woman to my right waves a falafel with dangerous gusto, a guitarist has joined the drummer and their audience stands enthralled, immobile with food and fresh air and goodwill. “This is a street fair, the first of the season,” says the voice at my left ear. “People get to talk to strangers, what would be the point, otherwise? I still think you should go back and get it, whatever it is.”

The sun is bright, yet it’s not hot at all, balmy; the sky gleams, air as clean as over a small town in Minnesota; the middle child ahead of me has just taken a lick from each of his friends’ ices in turn, this is surely the loveliest of Sunday afternoons. “Just a mangy shawl,” I say, “nothing much. Still, it’s intricate handwork and only four dollars, the price of a movie, I guess I’ll buy it after all.” But now there is no place to go. We stand, facing each other, and smile. He is not wearing sunglasses and squints down at me; his hair falls across his forehead. His face turns attractive when he talks, even more so when he smiles; he probably takes lousy photos, I think, at least if he insists on being serious in front of a camera. He wears a frayed, pale pink shirt, rolled up at the sleeves; the khaki pants are baggynot gay, anyway, I think; the way pants fit is one of the few remaining, if not always reliable, ways of tellingtennis shoes without socks. “I’ll walk back with you,” he says. “You won’t lose your friend, the whole mess is only a couple of blocks long, you’ll run into each other sooner or later unless she decides to give up on the whole area, of course.” “She won’t,” I say. “She lives down here.” He has begun shouldering his way back toward where we’ve come from and says, over his shoulder, “so do I. My name is…”

Now IT’S THURSDAY. We ate out Sunday and Monday, at my apartment on Tuesday, Zabar’s cold cuts at a party given by a colleague of mine on Wednesday. Tonight he is cooking dinner at his apartment. We are in the kitchen, talking while he makes a salad. He has refused my offers of help, has poured a glass of wine for each of us, and has just asked me if I have any brothers or sisters, when the phone rings. “Well, no,” he says. “No, tonight’s a bad night for me, really. No, I’m telling you, this shit can wait until tomorrow….” There is a long silence while he grimaces at me and shakes his head. Finally he explodes: “Oh, Christ! All right, come on over. But two hours, I swear, if you’re not set in two hours, the hell with it, I’ve got plans for tonight….”

“This dope” he groans at me, disgruntled and sheepish. “1 wish he’d get out of my life.

He’s a nice guy to have a beer with, but he’s got nothing to do with me except he plays tennis at the same place and works for the same firm, where he keeps falling behind and then he needs a crash course on his homework, it’s like junior high. He’s not too smart and he’s got no guts whatsoever. He’s coming down at eight, same old thing, some stuff he should’ve done two weeks ago and now he’s panicking. I’m really sorry. But we’ll go in the bedroom and you can watch TV out here.”

“I’d rather go home,” I say. “No, you don’t,” he says. “Don’t go home, that’s just what I was afraid of. Look, we’ll eat, you do something for a couple of hours, call your mother, whatever you feel like, and we’ll still have a nice time after he leaves, it’ll only be ten, O.K.?” “I don’t usually call my mother when I’ve got to kill a couple of hours,” I say. “I hate the idea of killing a couple of hours, period, I wish I had some work with me….” “Take your pick,” he says, “all you want, help yourself,” holding his briefcase toward me eagerly, making me laugh.

“All right,” I say. “I’ll find something to read. But

‘

/ go in the bedroom and I don’t even want your friend to know that I’m here. If he’s still here at ten I’ll come out with a sheet over my head on a broom, making lewd gestures.” “Great.” He beams. “I’ll take the TV in anyway, in case you get bored. And after dinner I’ll run down to the newsstand on the next block and get you a bunch of magazinesfor looking up lewd gestures you might not think of on your own.” “Thanks,” I say, and he grins.

After salad and a steak, we drink coffee in the living room, sitting side by side on a deep couch covered in blue cotton faded almost into gray at the armrests and frayed along the piping. “What do you do to coffee,” I ask. “Do,” he repeats, perplexed, “nothing, it’s done in a percolator, isn’t it O.K.?” “Listen,” I say, “I’ll take a rain check on the magazines if you get me that Gide down, in the shiny white jacket, on the left top shelf in the dining room, the spine caught my eye at dinner. That man’s always been plenty lewd for me.” But when he pulls down the book it turns out to be in French. And the Kafka, which fell down when he dislodged the Gide, is in German. “Never mind,” 1 say. “Would you have Belinda’s Heartbreak? Better yet, how about Passions of a Stormy Night?” “I’m sorry,” he says, “I don’t believe I have either of those….” His careful, uneasy tone of voice annoys me even more. ” War and Peace, then,” I say spitefully. “In that rare, exquisite Japanese translation.”

He lays down the two books he has been holding and puts his arm around me. “Sweetheart …” “And,” I say, in a voice as petty and unpleasant as I feel, “it’s a little premature, calling me sweetheart, isn’t it? We’ve known each other for all of ninety-six hours.” He draws me toward him and hugs me tightly. “Look, I can’t tell you how sorry I am, this is a makeshift, a half-assed… I’ll just call it off.” As soon as he turns toward the telephone I feel ridiculous. I clear my throat, swallow loudly, and say, “Forget it. It’ll take me two hours just to read the paper, and if you’ll give me some stationery I’ll write a letter I’ve owed for months, it’ll be a boost to my conscience. I’ll need a pen, too.”

He grins, relieved; walks over to a large oak desk at the other end of the living room, comes back with half an inch of fine, cream-colored paper; hands me the fountain pen from the inside pocket of his suit jacket, and lugs the TV into the bedroom. “I really hope you don’t mind too much,” he says. “This won’t happen again.” I cannot guess how thoroughly he will keep his promise.

By the time the intercom buzzes I’m settled on his bed, leaning into one of the pillows I’ve propped against the wall, my knees drawn up, his thick pen solid and comfortable in my hand. I hear two men greet each other, but once they begin talking steadily I can rarely make out separate words.

I write the letter (“… met this man a few days ago, nice start, very different from Gerry, who’s more than happy with Harriet these days, you remember her…”) take a cursory glance at the Times, look at my horoscope in the Post: “Theories are easily expounded, discounted because everyone knows what they are. Keep early hours clear for urgent purchases.” Just once in my life, I think, I’d like to understand my horoscope. I stretch out my legs, scrunch down on the pillow. During the hours I’ve spent with him here I’ve paid little attention to my surroundings. Now I find there’s not much to look at. It is a large, high-ceilinged room, the floor covered with the same gray carpet as the hallway and the living room. The walls are white, completely bare. The platform bed with its thin foam pallet is king-size and appears small. The sheets are white fresh, I notice, as they were on Monday, how often does this man change his sheets?the blanket pale gray, there is no bedspread. The two tall windows in the wall to the left of the bed are covered with bamboo shades, painted white. On one side of the bed stands the chair now holding the TV set; an end table of the same wood as the platform flanks it on the other side. The lamp on this table has a white shade, a round, white and blue basethe kind made from a Chinese vaseand a 75-watt bulb. I’m glad for the graceful lamp base but I think: wherever else he may do it, this man clearly does not read his original-language books in bed; why would anyone want to miss out on one of the most satisfying pleasures available? All he’d need is a better bulb, a few more pillows, and a reading lamp….

I wonder what he thought of my bedroom. Less than half the size of this one, painted by myself and two women friends in an elusive pale peach, the precise shade of which I agonized over for close to three months. It had been worth it. I wonder what he thought of the flowered comforter, the matching curtains and sheets and pillow cases, the three tattered Greek throw rugs, the trinkets from each one of my trips crowding the surface of the chest, the makeup table, the bookshelves; the piles of junk mail and magazines and paperbacks heaped on the floor on either side of the bed, the three empty coffee mugs, the overflowing ashtrays, the Chinese takeout container empty, but with a fork still stuck in it; the laundry stuffed into a pillowcase leaning in a corner; the newsprint photos of Al Pacino and Jack Nicholson stuck in the frame of the mirror above the table, along with a Polaroid of my broadly smiling parents and one of myself with a four-year-old cousin in Coney Island; and a postcard of Norwegian fjords, sent by a friend, and one of the Sicilian chapel I’d fallen in love with two years ago. And the framed New Yorker covers on the wall, and maps of all the countries I’ve been to, special cities circled in red; and my favorite: a stained menu in an ornate silver frame, Luchow’s, the first New York restaurant I’d ever been to, twelve years ago.

Now this room here, I say to myself, is too plain to be called plain. It’s austere, if you want to be charitable, or chic, if you want to be snide, or boring, if you want to be honest. It is not, in any event, a room you’d call cozy. Hasn’t anyone ever told him people put stuff on their walls? With his job he’d be able to afford some nice prints; and for the amount he must have paid for that monster of a Stella in the living room he could cover these walls in gold leaf….

The voices are louder now. It’s almost nine o’clock. I get up off the bed, and walk past the tall chest of drawers with ornate brass handles and some scrollwork in the wood; a long, narrow Parsons-type table stands next to it, holding a twin to the lamp on the bedside table and stacks of professional journals. And there is the closet. It is wide, with two doors that meet in the middle. The right one creaks loudly when I pull them both open: I stand stock still, holding my breath. But the unseen stranger’s voice has risen to almost a wail, while his purrs along, low and controlled. I feel like a sneak; as you should, I tell myself, that’s just what you are.

Beyond the doors, the closet extends to the ceiling. There are two deep shelves above the clothes rack. From what I can tellonly the front edge of the top shelf is within my range of visionit holds tan leather luggage, heavily scuffed; a camera case, ski boots, and three black vinyl folders labeled, across two-inch backs, “taxes.” The shelf below houses five heavy, crew-neck sweaters: two dark blue, one black, one off-white, one maroon; and four stacks of shirts, every one either light blue, pale pink, or white. (“I call Brooks Brothers now, once a year,” he will tell me, some days later. “They send me the shirts and I don’t have to go there. I hate going in stores.” When a shirt shows signs of fraying at the cuffs and collar, he keeps it in a separate pile and wears it at home, so I will learn; the man at the Chinese laundry returns the clean and pressed but frayed shirts bundled together, separated from the rest. If a shirt acquires a stain that cannot be removed he throws it out.)