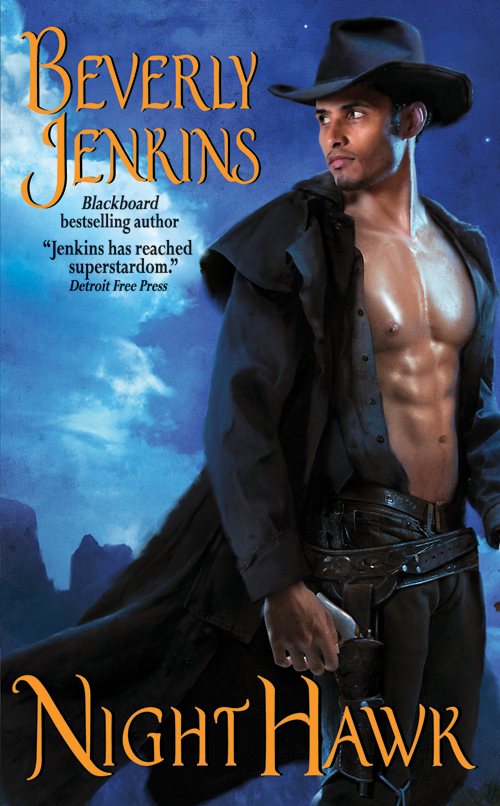

Night Hawk

Authors: Beverly Jenkins

Night Hawk

Beverly Jenkins

Contents

Coast of Scotland

April 1889

A

somber Ian Vance stood over his mother's headstone while a gale blowing in from the North Atlantic raised his black duster like wings. During his life, he'd been blessed with the love of two women, and now both were gone. His wife, Tilda, died at the hands of a murderer named Bivens, and his mother from loneliness and broken dreams.

He gazed ruefully out at the jagged cliffs of Scotland's coast. Angled-winged seabirds called to one another as they dove in and out of the spray. His mother, Colleen, had been like them, rising and falling on the winds of life. No matter the storm, she always had a ready smile and a twinkle in her eye to let him know she'd one last trick up her sleeve, but when her beauty faded, the men who'd eagerly provided for her in exchange for what she provided in bed faded, too. In her world, youth trumped age, and there were no tricks up the sleeve for that.

The sound of carriage wheels traveling over the cobblestone road that ambled past the small cemetery caused him to glance up. The black coach rolling into view was a lavish one; the red and gold crest emblazoned on the door all too familiar. It belonged to the local laird, Ian's grandfather.

Two decades ago, and with Colleen's blessings, Ian had fled Scotland for a new life in America. He'd vowed never to return to the land of his birth, but the letter he'd received from Colleen's ancient cook about his mother's passing drew him back to pay his respects.

He watched the coach come to a stop. He'd expected his grandfather to get word of his presence; he hadn't expected to be sought out.

The stooped, weathered man who descended the step did so slowly. His hair was snow white and Ian realized he had to be in his late seventies. Colleen had given birth to Ian at a young age and without the benefit of a husband. That sin alone guaranteed her soul a seat in hell, but the revelation that the sire had been a Black seaman with the British Navy so enraged her father that he'd banished her, his only child, from their home.

And now that same man approached. A gnarled cane aided his steps and his sun-lined face held the same green eyes as Ian's. If Colleen's father had been furious about the birth, he'd been doubly so to learn that her half-Black bastard child bore his name.

“I heard you were here,” his grandfather offered by way of greeting while critically assessing Ian from head to toe.

“I've no intention of darkening your doorway, if that's your thinking.”

“Why are you here?”

Ian let the pun pass without comment. “I only recently found out about her death. Came to pay my respects.”

His grandfather turned his eyes to the cliffs and the roaring sea. While the wind whipped at their clothing and the tall grasses covering the treeless plateau, he appeared to be lost in thought or maybe in the past. “I done her wrong,” he finally intoned in his thick Scottish burr. “She was me only child.”

Ian kept his face void of emotion because the admission had come too late for that only child.

The elder Ian added quietly, “She loved you.”

“And I her.” But there'd never been so much as a smile from her father for Ian.

“You passed university at Edinburgh.”

“Yes sir, in the law.”

“That what you do over in the colonies, practice law?”

“A bit, yes.”

“Everybody there dress in that fashion?” he asked, pointing the cane disdainfully at Ian's Western-style leather clothing.

“No.” Ian supposed he did look out of place in his wide-brimmed hat and the leather duster over his black shirt, leather trousers, and gun belt, but he felt no more out of place than he had growing up. England's vast navy and merchant fleets were made up of men from all over the world, and as a consequence there were mixed-race children throughout the empire's port towns. But in the tiny Scottish coastal village of his birth, there'd never been anything like Ian before, and many of the locals went out of their way to make certain he knew it. As a child, to be singled out and taunted simply for one's parentage had hurt, but he'd used the slurs and bullying to make himself stronger and smarter. To cower and cry would have proven true all the negative things he'd been told about a man with his blood. He'd found prejudice in America, too, but he was no longer a child and could hold his own.

His grandfather reached into a pocket of his worn red waistcoat and withdrew a small leather pouch that he passed to Ian.

“What is this?”

“The dowry I never allowed your mother to have. It's your inheritance now.” And apparently he had nothing more to say. Turning away, he began walking to the coach where his driver stood ready and waiting beside its opened door. After taking a few more steps, however, he stopped and glanced back. The aged green eyes that met Ian's held hints of regret. The two men faced each other with only the past and the howling wind between them until his grandfather spoke. “Because she loved you when I could not, go with God, Ian, but never return to my lands again.”

Tight-lipped, Ian watched as his grandfather climbed inside and the coach rumbled away.

Ian put the bag of gold into his coat and refocused his attention on his mother's headstone. He offered a few prayers and whispered a final good-bye. “Farewell, my beautiful Colleen. May God love you as much as I. Rest in peace.”

He mounted his stallion, Smoke. Taking one last look around at the wildly beautiful place that would hold her, and in many ways himself, for eternity, he reined his mount around and galloped off to meet the ship that would sail him back home to America, where he was known as a bounty hunter named the Preacher.

The wind gave our children the spirit of Life.

CHIEF JOSEPH

Dowd, Kansas

May 1889

P

reparing dinner in the kitchen of the whorehouse where she worked as the cook, Maggie Freeman decided she'd had enough. If the owner, Hugh Langley, tried to force himself upon her again, she'd have to give her notice. In truth, such a decision made little sense. In a town as small as Dowd, Kansas, the chances of hiring on somewhere else were slim to none, but she knew she had no other choice.

Maggie's father, Franklin, a Black Civil War veteran and staunch Lincoln Republican, and her mother, Morning Star, a woman of the Kaw tribe, had been killed in a fire when Maggie was twelve. She'd be twenty-five in December and had been on her own since the day they died.

Dowd was a dozen miles south of Kansas City and she'd been employed at Aunt Phoebe's whorehouse for two weeks. Her previous position as a washerwoman in the household of the mayor and his wife in the neighboring town of Madison had been short-lived. Because it was a well-known fact that all Blacks and Natives steal, Maggie had been accused of taking a brooch that belonged to the mayor's wife, and in spite of her fierce claims of innocence she'd been promptly arrested and jailed. The brooch, which had actually been misplaced by its squat, hairy-chinned female owner, was found the next day in the pocket of one of the woman's day gowns. The charges were dropped, but there'd been no apologies forthcoming from the mayor or his wife, nor had they offered to reinstate her. So Maggie'd saddled up her old mare and ridden the six miles west to Dowd where the only job available had been at Aunt Phoebe's whorehouse. She'd taken it gladly.

Now it appeared as if she would have to leave Dowd as well. Two nights ago, Phoebe's business partner, Hugh Langley, had stumbled into Maggie's room smelling of cheap whiskey, and tried to force his way into her bed, again. Showing him the business end of her father's old Colt dampened his enthusiasm, but she'd had to endure his sullen, hate-filled slurs before he finally removed himself and left her in peace. That was the third time she'd had to run him off. After the first incident, she'd tried to talk to Phoebe about his behavior, only to be waved off dismissively and told that Hugh was the scion of a wealthy family, accustomed to getting what he wanted, and that Maggie should be honored by his interest. It became clear that there'd be no help from that quarter so she'd taken to sleeping with the Colt beneath her pillow.

Putting the drunken Langley out of her mind, she concentrated on spooning the biscuit dough into the wooden dough bowl. She'd just picked up the rolling pin when she was suddenly forced against the counter and held there by someone behind her. She felt hands frantically snatching her shirt out of her skirt and forcing her skirt up her legs.

“I got ya now, squaw!” Hugh Langley crowed, his hot, foul breath against her ear.

Fighting to buck off his heavy weight and keep his hands out of her clothing, she cried out and reached for something to arm herself with. He spun her around and tore open her shirt all in one motion. She slapped him hard. In the split second that it took for him to grab his stinging cheek, she swung the heavy rolling pin across his jaw with all the force she had. The blow sent him staggering. His knees buckled. Simultaneously stumbling and falling, he hit his temple hard against the sharp corner of the wooden table in the center of the small kitchen and collapsed in a heap to the floor.

In the silence that followed, she tried to calm her racing heart, hold her torn shirt together, and not cry out from the fear that had flooded her during the attack. Wary, she moved closer to where he lay unmoving. She held the pin high and at the ready in case he tried to grab her again, but she saw blood creeping from beneath his profiled face.

Suddenly Phoebe swooped into the kitchen, asking, “Maggie, are those biscuitsâ” She glanced first at Maggie standing as she was holding the raised rolling pin, then down at Langley sprawled out on the floor lying in a widening pool of blood, and her overly made up eyes widened. She dropped to her knees beside him and screamed, “Someone run for the sheriff! She's killed him! Oh my Lord! She's killed Hughie.”

“He attacked me!”

Phoebe's eyes held fury. “You're going to hang!”

“I didn't kill him! He attacked me and hit his head! Look at my shirt!”

But it didn't matter. The sheriff arrived, and after all the yelling and accusations stopped, Maggie was once again arrested and taken to jail.

Sullen and angry, she paced the small cell like a cat in a cage. No one cared that she'd been trying to protect herself. No one cared that her ripped shirt bore clear evidence of Langley's dastardly intent. The sheriff, a middle-aged man named Wells, seemed to be a reasonable person and had asked that Phoebe find Maggie a shirt to replace the torn one, but he still put the shackles on her wrists and walked her past a crowd of jeering townspeople and down the street to the log building that held his office and the jail.

“Going to be at least two weeks before the circuit judge comes back this way,” he told her once she was inside the cell with its straw-covered floor and bare mattress. “But I'll try and make your stay as comfortable as possible.” And he departed.

Although she knew crying wouldn't alter her plight, tears of rage and frustration wet her eyes before she angrily dashed them away. It was difficult being a woman alone, having to secure food, shelter, and, most of all, safety. With no family or husband, she was easy prey for thieves and two-legged coyotes like Hugh Langley, but she was determined not to give in to fear. The year after her parents' death, she'd worn fear like a coat. Her parents had loved her, educated her, sheltered her as best they could, and then to find herself suddenly without them had been the most frightening thing she'd ever known. Some of her neighbors had taken her in at first, but in the end she was just another mouth to feed. She'd gone door to door in an attempt to find day work but the roles were already filled by older women who lived nearby. Finally the sisters at a convent outside Lawrence took her. They gave her meals and a place to lay her head at night in exchange for chores like scrubbing floors and working in the kitchen. She stayed for six years.

Although the sisters had been charitable, not a day went by without them reminding her that she would be condemned to hell if she didn't renounce her ties to her Kaw mother and the rest of her

savage

kin, and transform herself into the godly young woman the sisters supposedly personified. It was a constant theme played out all over the country as churches and schools did their best to separate Native children from their tribes, their parents, and the cycles of life that had been practiced long before the landing of the first Europeans. According to the sisters, Maggie's mixed blood presented an even bigger challenge for her immortal soul, seeing as how men and women of African descent were considered inferior in every way, and it didn't matter that her parents had raised her to be proud of her blood, the sisters and the church were right and Maggie's parents wrong.

To stop the daily lecturing, Maggie let them believe she agreed, but in her heart she continued to honor her mother and father and her heritage.

In the jail later that evening, after a dinner of ham and beans, Maggie got her first look at Hugh Langley's daddy, Hank. The big, burly man and six other men rode into town with torches in their hands, firing their guns and circling the jail. She quickly moved away from the window to avoid being seen and prayed the sheriff would stop them before they stormed the jail.

The rapid answering shots of a Winchester sent her hurrying back to the window. A crowd of townspeople had gathered, but it was impossible to tell if they were there to support the riders or just being nosy.

The sheriff's voice rang out, “Hank Langley! Next man to fire is under arrest!”

The steeliness in his tone and raised gun brought the action to a halt. Maggie prayed Langley and his men didn't respond with shots of their own.

Langley called out to the sheriff in a reasonable-sounding voice, “Now, Sheriff, I know you were elected to uphold the law, but that nigger squaw killed my son!”

The crowd reacted with a vocal agreement. From behind his still raised rifle, Sheriff Wells disagreed, “Coroner Potts says differently. Hugh died when he hit his temple against the table just like she claimed, so we'll let the judge sort it out at trial.”

“That'll take too long!” Langley shouted back angrily. “I want justice, now! Step aside!”

The sheriff's voice remained firm. “She stays until the judge shows up. Take your men and go before I charge you with interfering with a peace officer.”

Maggie didn't know the sheriff personally but she was pleased that he respected the law enough not to hand her over. Vigilante justice was common all over the West, and she had no desire to swing from the end of a rope for something she didn't do.

The sheriff barked again, “Go home! All of you!”

Maggie saw Hugh's father's angry face in the flicking light of the torches. He gave her cell a long, ugly look as if he knew she was in the shadows watching, but he signaled his men and they thundered out of town.

The buzzing crowd dispersed soon after and Maggie finally exhaled her pent-up breath.

For the next three nights, Langley returned, and with each visit the numbers of men riding with him increased. They didn't rush the jail, but were seemingly content to ride back and forth with their torches held high while yelling, calling Maggie nasty names, and threatening her life.

By the fourth morning, the sheriff came to her cell to tell her of the decision he'd made. “I'm taking you up to Kansas City on the afternoon train. You'll be safer waiting on the judge there. I don't think Langley's got the nerve to follow you to a place that has United States marshals.”

She hoped he was right. She also hoped she'd be able to get a full night's sleep there instead of tossing and turning and worrying if she'd be dragged out of the jail to her death.

“Got a real dislike for Hank Langley,” the sheriff revealed. “He and his money have been running roughshod over folks here for a long time. I ran for sheriff because I was tired of it.”

“When do we leave?”

“Train comes in around eleven. Langley's got men watching the place so I'm hoping we can get to the depot and on board before he gets word.”

She'd seen the men in question lounging against the doorway of the general store directly across the street. “Will you let me have my Colt in case we're ambushed?”

“No, but I'll do all I can to keep you safe.”

Maggie wasn't happy. Her father had taught her to shoot at a young age. Being able to defend oneself was necessary, just as it might be on the way to the depot, but the sheriff had confiscated her ancient Colt and her small cache of personal belongings upon her arrest. The only thing she'd been allowed to keep was her father's old army jacket, which she wore to keep herself warm and the memories of her parents alive.

“You ride?” he asked.

“Yes. My horse's over at the livery. She's old and slow, though. Not a mount I'd want for a dash.” Like most farm girls, she started riding before she could walk.

“I'll loan you one. Where'd you get that coat?”

“Belonged to my father. He was with the First Kansas Colored and a sergeant with the Ninth Cavalry. He and my ma are dead now.”

“Sorry to hear that. I'd just as soon let you go, but folks here wouldn't like that, so I have to leave it to the judge.”

“I understand. Thank you for standing up to Langley.”

“You're welcome.” He picked up the tray and plate that had held her breakfast of dried fruit and a small piece of bacon, turned the key in the cell door, and returned to his office up front.

The sheriff returned for her later. Maggie had already decided that if she had a chance to escape she would. There would be no justice for a woman with her blood because there never had been, otherwise the Democrats wouldn't be killing her father's people all over the South, and her mother's people would still have their lands, instead of being forced to eke out a living in the dusty poor soil of Indian Territory. She was a descendant of strong men and women on both sides of her family, and she refused to have her fate decided by courts that had proven time and again that people with her ancestry didn't matter.

“I'm going to have to put the bracelets on you again.”

“How am I supposed to ride?”

“Very carefully.”

By his smile, she assumed he meant that to be a joke but she failed to see the humor. Apparently her cool gaze gave him second thoughts because he cleared his throat and said, “Give me your wrists, miss.”

She complied and he clapped on the metal cuffs. He'd cuffed her wrists in front, but in spite of the restraints, she managed to get her foot in the stirrup, and use her immobilized hands to grab the horn of the saddle and pull herself up. Once mounted, she saw that people along the walks had stopped and were staring her way. A man whom she'd seen positioned in front of the general store most of the morning suddenly tossed his toothpick aside and eyed her and the sheriff keenly. She assumed the man to be one of Langley's employees.

“That's one of Langley's men,” the sheriff corroborated while lifting himself into the saddle of a big gray stallion.

The Langley hand yelled out, “Mr. Langley ain't gonna like you trying to sneak her out on the train, Sheriff.”

Maggie wondered how he'd learned about the sheriff's plan, and from the anger flooding the lawman's face, it appeared he was wondering the same thing. Wells ignored the challenge, however. “Let's go.”

Holding on to the reins and the horn as best she could, Maggie rode out of town under the sheriff's escort and the hostile eyes of the people of Dowd. She saw the Langley employee run to his horse and ride hard west. She wondered if she'd make it to Kansas City alive.