Nico (12 page)

Le Kid puffed on his spindly joint. âDo you sink zey broat 'im guerrls?'

âProbably,' I said, âalong with

Le Figaro

and the latest copy of

Elle

magazine.'

His lips puckered tighter than a tomcat's asshole. I was not being â

sérieux

'. Le Kid had inherited his mother's sense of humour.

When we arrived in Cagliari the local promoter picked us up in his 2CV. He was sweet, a fan. That meant he probably didn't know what he was doing. Nico stole his shades. Bendini turned up; he brought with him his assistant Mario and his secretary Marina. My God, maybe it was the heat, but she had a definite look of Leonora the Leopard Lady. Le Kid broke into a sweat. Instantly he wanted to mate with her and started spraying his scent ⦠âI am Nico's son ⦠I was een ze Factory wiz Andee War'ol.' She was going to drive us all crazy.

The hotel had a private beach. We all scuttled down there like nesting turtles. Marina did her stuff â the whole Birth of Aphrodite routine. Only Bendini remained free of the âlibidinous waves'. She jiggled her tits in his face, but the little fellow was so myopic he missed it. The rest of us just ached and dug ourselves deep into the âpagan sands'.

Maybe fifty people showed up at the gig. A girl in a day-glo swimsuit asked me if I was Nico.

We did a couple more Club 18-30 Nostalgia Nights. Le Kid was petulant and pouting.

âZe Carnegie 'All ⦠ze Carnegie 'All ⦠my muzzere should play ze Carnegie 'All.'

Bendini was running around the island sticking up fly posters. They slithered down again before you could read them.

It was the height of Michael Jackson

Thriller

fever. At Klub Kinky the cruel disco heat burnt and blistered our pale Northern European skin. Kids were circling round us, body popping and moonwalking. The lights went down to reveal: Death at the Heart of the Disco. We lasted about ten minutes. They just played a 12-inch megamix of âBilly Jean' over what we were doing and faded us out.

I got the feeling Bendini had simply phoned up his friends, any friend, who might possess a Nico album, and asked them if they wanted to do some shows. Klub Kinky, Cagliari, was as far away as Nico could ever get from âZe Carnegie 'All'. Kidnappers, bandits, donkeys, tourist villages, glazed terracotta tiles, handwoven peasant blankets, coloured rugs, baskets, sun, blue sea, white rocks, sand they had a-plenty, but Billy Jean was not my love. Le Kid was not my son.

Civitavecchia

The harmonium was swaddled in its old blanket, like a refugee's sad bundle. It was Nico's only real possession. Without it she had nothing to trade â even though its bronchial wheeze spelt instant death to the disco children. Nico's songs of mortality and decay were not compatible with the dominant rhythm of the eighties, especially not for honeymoon couples and resort developers.

A swarm of ants was teeming about their insane and remorseless duty at my feet. It was 3.00 p.m. Siesta. The cicadas were chattering and telegraphing their nervous messages to one another. Our backsides were burning on a hot stone bench. Nothing of human intent or design was moving on Civitavecchia station. Except a single, silent tear down the side of Nico's face.

âI guess I'm through,' she said.

I stared down at the ants.

âThey want disco music now.'

I put my arm around her shoulder. She was sweating and shuddering. She looked up at the sky, trying to keep back the tears that were brimming in her eyes. This wasn't the familiar withdrawal hysteria I'd seen all too often before. Certainly the smack wasn't coating every nerve and cushioning reality; instead what she was seeing was more than just her misery, what she was feeling was more than her self-pity.

âWhat can I do? I can't do anything else.'

âYou've still got your voice,' I said. âCan't you write some more songs? You need to make a record â get your face about a bit. It's no good busking around discos hoping to pick up pennies to score. People have got to

want

to see you.'

âI know. I know,' she sighed, weary at the prospect of having to rebuild her derelict career.

âBut look,' I said, trying to reassure her, âit's not like you have to start from nowhere. People don't need to be convinced. It's just â¦' How to put it? â⦠It's just that, well ⦠you're bone idle.'

She looked at me, curiously, then laughed. âI guess you're right ⦠Aaandy always said I was laaazy.'

âYou should make a record, Nico â then the tours'll have some meaning. You won't need to play seaside discos.'

Le Kid was endlessly making and remaking his one silly little joint with a few meagre crumbs of hash. âMy muzzerre should play â'

I came in on the chorus. âDon't tell me â âZe Carnegie 'All.'

Suddenly Dr Demetrius began to devote his powers of persuasion to something other than tourism. His ultimate goal was, of course, to secure more tours, but it had become obvious even to the most dedicated holidaymaker that no one would be going anywhere until Nico became a going concern.

Nico had tried to run away a number of times after the Italian disco tour, but no one else really wanted to look after her. She'd camp out on sofas, stretching her hosts' generosity to the limits, until they'd have to say or do something hostile. I'd heard that at the height of Sergeant Pepper mania Paul McCartney's chief concern was in getting Nico out of his living-room.

She tried it on everywhere, even my girlfriend's. They got on like two cats in a sack. At first she'd be charming and sweet and talking about recipes, and then things would start to turn a mite strange. For instance, you'd find suggestions and alterations being made to your TV schedule. Comedy programmes were bypassed for anything even remotely connected with Death. She moved on to a friend's place. But when he found all his spoons had become mysteriously bent and burnt, and his pretty young wife expressing fascination with Nico's little pochette of pinkish brown powder, he put her on the first available flight to New York â where she bugged my brother for floor space.

It wasn't that nobody liked Nico. In fact they were, mostly, very fond of her. But she was a junkie. Junkies, any kind, are invalids with criminal tendencies. They can't be trusted. It's not their fault. Their need is greater than they are.

You witness their vulnerability and you want to help because they're your friends or colleagues. But you know they're going to let you down. I'd implored Echo to come and stay with me and sweat it out; wisely he'd turned down the offer. His voice was fainter than ever on the phone:

âThanks, Jim ⦠But what I really need ⦠is the stuff.'

He was being honest. Moreover, he knew if he accepted my offer he'd be forced into dishonest behaviour. I think that's why we'd fallen out. I just wasn't prepared to walk the same Via Dolorosa.

But, in order not to succumb, you're forced, as a witness, to harden your will in a manner ultimately injurious to the spirit. I think we all loved Nico. But those of us especially who weren't prepared to sacrifice themselves to smack found it necessary to fix a limit to that affection. And that's unnatural. The way we did it, mostly, was through humour. It wasn't meant to hurt her, more to protect ourselves from her predatory influence.

It reached an insane level, though, when Demetrius conducted an interview on the phone to a music magazine, impersonating Nico. As the journalist got suckered in deeper, Demetrius/Nico got wilder and more fantastic in his claims. The interview closed on a major scoop/revelation, that Andy âisn't really, well, you know, strictly â “gaay” ⦠in fact, we've often shared a very rich and rewarding love life together over the years.'

Number 23 Effra Road, Brixton, was owned by a Mrs Chin, a respectable, church-going, Jamaican landlady who'd married a Chinaman and ran a small grocer's shop down Coldharbour Lane.

The first time Demetrius and I looked over the flat we thought it was perfect, mainly because we liked the two imposing white stone lions on the porch. The place itself consisted of the top two floors of an end-terrace Victorian house.

Many people from the North of England are anxious about living in the unlovely city of London. However, Manchester man that he was, Demetrius had decided, about time, that Nico had to be seen on the scene. She had to get with a solid record company. Manchester was too small and specific. There, you had to be eighteen and living in a squat in Didsbury to qualify, you had to be new. Demetrius had to find a kind person in charge of an approachable record label. (There was no sense at all in talking to the Praetorian Guard of little girls in miniskirts who are employed to repel the advances of any itinerant chancers hoping to score a quick advance.)

We had a look round the flat. Three bedrooms, living-room, kitchen, bathroom. Clean. White. Discreet. Perfect. It was an ideal safe-house from which Dr Demetrius could launch Nico's Teutonic terror campaign on the funky phonies of south London.

He'd had his car fixed up. He'd invested in a new suit from High and Mighty. Big silk kipper tie. New trilby from a good milliners in Halifax. Church's shoes. He looked like a swell from

Guys and Dolls

, but he stood out like a sartorial giant in Brixton's ghetto of post-punk pretension. Mrs Chin was impressed.

âAn' when would you be intendin' on movin' in?' she asked.

âAs soon as possible, Mrs Chin, depending, of course, on your own commitments.'

She was flattered that a professional, a âdoctor', might be taking up residence.

âAn' would it be just you an' the music teacher?' (Nico!)

âYes ⦠very quiet. She may sometimes have a couple of friends round for a glass of amontillado and some Schubert

Lieder

, but apart from that she lives a very frugal and reclusive existence ⦠I myself write poetry in the evenings. So, other than the occasional melancholy rattle of the typewriter, there would be very little incursion upon the sensibilities of your other tenants and, of course, your good self.'

âVery nice,' said Mrs Chin, impressed by the good doctor's mixture of dignitas and warm bedside manner. âCare for some fried plantain?' She offered us a seat at the kitchen table.

âAn' what is it you do for a livin'?' she asked me.

I had to fall in with Demetrius's scheme of things. Before I could utter a word he spoke for me.

âJames is a medievalist, a diligent scholar reinterpreting the rich legacy of our written history. He spends most of his waking hours researching Carolingian manuscripts in the Bodleian Library â a very painstaking and selfless task, Mrs Chin, I can assure you. Would it be any inconvenience if James were to occasionally prevail upon your hospitality whilst undertaking vital extramural research at the British Museum?'

She looked me in the eye. I could tell she suspected I was a wrong'un. I swallowed my hot slice of plantain and tried, as best I could, to assume the smile of a medievalist.

Planet Pussy

had been invaded by a dreary Garbo movie, and then metamorphosed via Brando's shaven crown from

Apocalypse Now

into a 1½-hour documentary on open-heart surgery. Nico had worked out how to use the video recorder.

Two honest English yeomen, John Cooper Clarke and Echo, were holding target practice in the kitchen. The targets were small black flies on the ceiling, the missiles were jets of blood squirted from hypodermic needles.

The brand new leatherette sofa had already become pock-marked with cigarette burns. Tea had been constantly made, rarely drunk, mostly spilt on the off-white electrostatic nylon carpet. The paper light shade had been torn down and mutilated by Echo, as it reminded him of a âstudent gaff'. A naked lightbulb exposed the bare walls. There had been a small mirror, but that had also been removed. There were two armchairs, the brown plastic type covered with cheap foam cushions; your neck stuck to the back whenever you tried to get up. No cooking had ever been done in the kitchen, but the place was filthy. The walls splattered with blood, putrefying takeaway cartons stacked on every available surface. In the fridge was a slow, sad, pink effluent waterfall of melted ice-cream.

There were no proper curtains (Echo was using them as bedding), just nicotine-yellow nets.

The toilet seat had been destroyed (Echo preferred the squatting position as he was prone occasionally to âa touch of the Michaels'). There had never been any toilet paper.

Demetrius had the back room downstairs as his bedroom. On the floor were heaps of dirty laundry, an overflowing half-abandoned suitcase, bottles of pills, a stack of hardcore porno mags within arm's reach of the bed, and a box of Kleenex ⦠scrunched up, semen-cemented tissues were dotted everywhere, like dead carnation-heads.

Upstairs on the right was Nico's room. You entered at your peril. The first thing that hit you was the smell of burnt heroin, hashish, and stale Marlboro smoke â it veiled all other odours, which was probably just as well. Heaps of junk had been deposited everywhere like a fleamarket stall â Nico T-shirts, duty-free bags and empty cigarette cartons, ashtrays piled high beyond overflowing. Nico had a severe catarrh problem, exacerbated by her chainsmoking. (She maintained that she never really started smoking until her habit began â before that she was the singing nun.) By her bed was a Coke tin. The Coke tin had a special function â as a repository for all the phlegm she was continually coughing up. Demetrius had once blindly taken a swig. It's the real thing.

My room was locked. With a chain â until Echo managed to pick his way in. It took him the best part of a weekend. While Nico and I went north to play a gig at the Blackpool Beer Keller to an audience of six (the owner said he didn't care if we went on or not), Echo moved in his entire family, plus pet punk poet pal John Cooper Clarke.

Clarke had just come out of an expensive, intensive, detox clinic â a posh Chelsea sanatorium for addicts of all persuasions, the Charter Clinic. He'd been there to clean himself up at the great expense of his record company. He emerged vulnerable, yet confident, ready to pick up his career. However, Demetrius thought it would be interesting to reintroduce him to Echo. His reasoning was that he felt sorry for Echo being ousted from Nico's employ, he felt somehow personally responsible for him. He thought maybe he could team Echo up with Clarke and together they would make hits â which is exactly what they did. What else are two junkies going to talk about? What else does their whole beleaguered belief system revolve around? Within a couple of hours (as long as it takes to cab from Brixton to Jackie Genova's place in Stoke Newington) they were back on the gear.

Demetrius couldn't bring himself to kick them all out, so a compromise was reached. Faith and the children were put on the first Intercity back to Manchester and Echo and Clarke would sleep in the living-room. Not that it could be actually called sleep, more a kind of stoned somnambulism.

John Cooper Clarke

His own creation. A slim volume. A tall, stick-legged, Rocker Dandy with a bouffant hairdo reminiscent of eighteenth-century Versailles and Dylan circa

Highway 61

. Black biker's jacket with period details, in the top pocket a lace handkerchief, a diamanté crucifix, and a policeman's badge pinned on to the sleeve. He wasn't gay or even camp, his tastes were what you might call School of Graceland. His favourite music was Rock'n'roll â big guitars, whacking great beat. His favourite eatery was any Little Chef. He particularly enjoyed the cherry pancake with whipped cream â it was consistency of product standard he relished as, without such little oases of sweetness, each day could be an endless series of disappointment, threat and anxiety. He and Echo were almost interchangeable. They both came from the same part of Manchester, they were both Catholics, they were both pure Rock'n'roll, and they both shared the same needle. The difference being, Clarke had a career.

He performed his poetry in a rapid-fire style taken from the Italian Futurists and a youthful predilection for amphetamine sulphate. His droning Maserati vocal technique sometimes blurred the brilliance of his writing, but everything he did or said had the mark of an individuality born of a true, self-inflicted suffering. Like Echo, he believed in Original Sin. And the Catholic sensibility is capable of nurturing the most original of sins.

He rarely liked to leave the flat, as he had a public persona to maintain. If he did venture out, then he had to prepare the

Grande Levée

. Hair back-combing could take an hour in itself. Leaving the house was like going on stage. (Echo once delayed his entrance on stage by a whole hour when he commented adversely on Clarke's choice of trousers. Since all his trousers were the same black drainpipes the choice seemed immaterial.) Both of them lived in a world haunted by superstitions and taboos of their own making. Clarke couldn't bear to be near things that weren't manufactured. The ânatural' world was a source of intense dread and disquiet. To tread on grass meant to come into contact with âthe world of worms', a potential holocaust under every cuban-heeled step. He was so like Echo, except his fame had projected him even further out of reality. With commitment and effort he might have become one of our finest People's Poets.

But another poet resided at 23 Effra Road.

Dr Demetrius was taking it all in his ambling stride: gold discs, silver discs, picture discs, black-and-white post-abstract expressionist Soviet constructivist St Martin's College of Art '81 tastefully depressing covers.

Miss Poutnose, the switchboard queen, showed us downstairs, through racks and racks of endless, imperishable product. At last, we were in the Hallowed Halls of Vinyl. To Demetrius it was like a private tour of a bank vault. He'd already planned, before artists and budget had even been discussed, to hit the record company for hundreds of promotional copies which he could use as tour merchandise.

Miss Poutnose brought us a glass of Evian water each. Demetrius's eyes followed her miniskirted behind as it tick-tocked enticingly out of reach.

The good doctor finalised an agreeable, though not profligately generous, budget. Master Jonty of the good old family firm Beggars' Banquet was cautious, aware of Nico's unreliability and limited marketability. What, he wanted to know, would be my role? I reassured him of my lowly, yet indispensable status, as arranger. This satisfied him â no one, not even Nico, was to distract John Cale, the producer, from his lofty purpose.

Dids

There was rarely a fixed personnel working with Nico at this time, except for a vague nucleus of myself, Toby, and a manic percussionist from south London called Dids.

Dids had actually emerged on the Manchester scene, banging bits of metal with post-punk art groups. He was a vicious, Puck-like creature, a bit like the kind of thing that used to vomit boiling oil from the towers of medieval cathedrals.

Dids had a haircut that resembled more a piece of topiary than anything one might recognise as a familiar style. It was a cross between convoy hippie and Bauhaus formalism. The sides were shaved completely, while at the back, hanging down his neck, was a raggedy mane. It added further to his elfin appearance. Dids had been brought up in East Grinstead, the south coast holiday resort that houses the H.Q. of the Scientology movement. Dids's dad had been a pal (though not a disciple) of L. Ron Hubbard, the âBarefaced Messiah' himself. Uncle Ron used to come round for Sunday tea when Dids was a kid. With such a charismatic figure parking his shiny new '61 Thunderbird outside his parents' inauspicious little semi Dids felt an early rapport with showbiz. âOw yez. Showtime starts when I leave my front doorstep.' He'd precede every remark with the self-affirmation âOw yez', his chest swelling like a bantam cock as he described the unique charms of Balham, his âmanor'. His friends were all car dealers, car repairers and car thieves, and they would give him bits of cars to play with on stage. Anywhere north of the river Thames was suspect to Dids, and as for

Das Kultur

, âOw yez. You can really push the mo'or on them or'abahns â nowha'amean?'

Nico modeling in French

Elle

1961

Nico, (third from left) at age 16 in Fellini's

La Dolce Vit

a

(Archives Malanga)

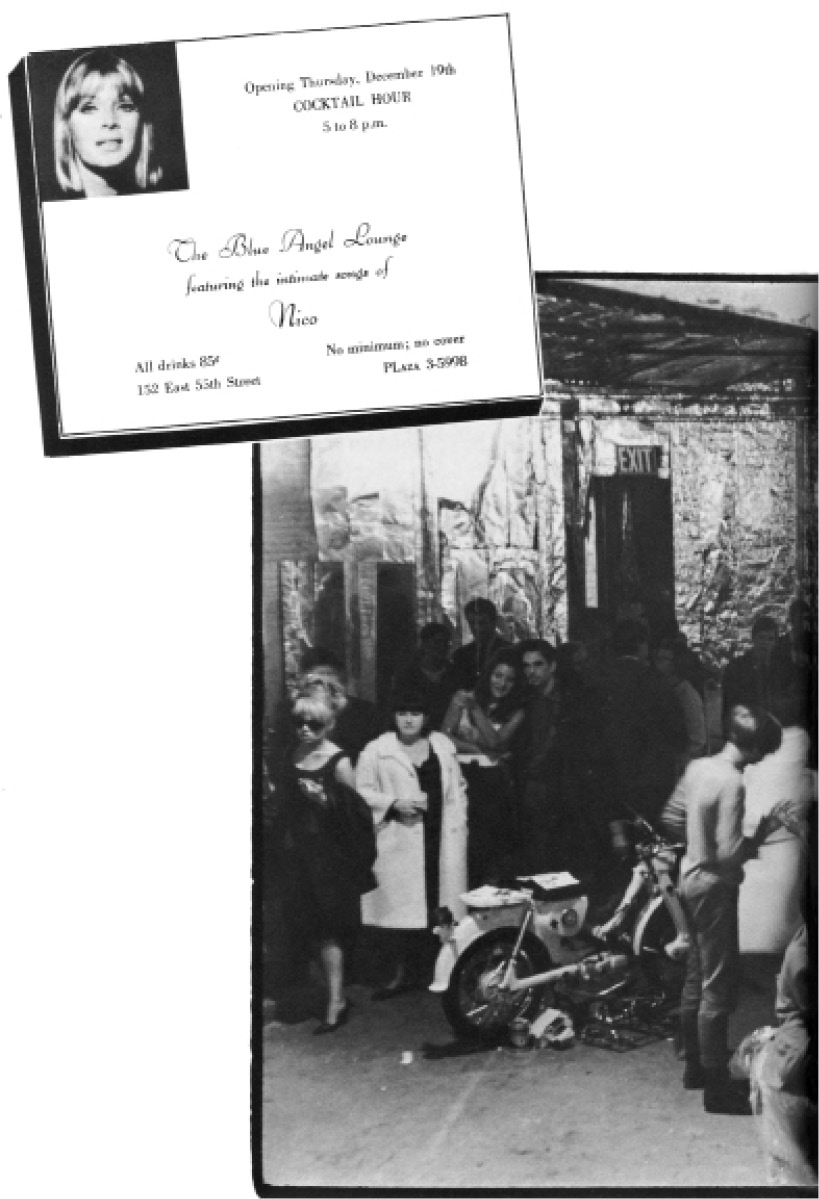

Original invitation to The Blue Angel Lounge, 1964 (Archives Malanga)

A party at The Factory (Fred W. McDarrah)