Neverland (37 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

“My son,” a voice I had not heard before called out, “come to me. You are mine.”

The geometry of the earth had changed, and we were surrounded by a sea of ice, and fog so thick I could barely see my cousin or the baby at all. Grammy was not there. All around us, in the whiteness, lay dead, torn animals, rabbits and sea gulls and mice and crabs. Some moving still in their moments of agony, their throats and shells and stomachs torn. Beneath the ice, the frozen faces of Gullah slaves, staring up at us.

From among the dead and dying a dark creature came, moving on hooves and hands, its skin spiny, its face eclipsed by a mouth that was open wide and studded with gray shark teeth

.

There, in its chasmic throat, was Aunt Cricket’s boiled and blistered grinning face. “My son,” it said, “I love you, you are mine, I am hungry.”

.

There, in its chasmic throat, was Aunt Cricket’s boiled and blistered grinning face. “My son,” it said, “I love you, you are mine, I am hungry.”

Aunt Cricket’s shredded lips parted, “Hallelujah!”

“Mama,” Sumter moaned.

“Why, I ain’t your

mama

, Sunny

,

you know that. Why Babygirl’s your mama.”

mama

, Sunny

,

you know that. Why Babygirl’s your mama.”

“No, you’re my mama, you’re my mama.” His eyes burst with tears. “I love you, mama, don’t let me do this, don’t let me.”

“HUNGRY,” said his father, “SACRIFICE TO ME.” The creature’s jaws opened and shut, and when they opened again, Aunt Cricket’s face was all but gone. Only a shred of her nose and mouth remained caught between its teeth.

“Not Governor.” I moved toward my cousin. “Give me Governor. What about will, Sumter? Do what you will, it’s a Neverland commandment, what do

you

will?”

you

will?”

Sumter was crying too much to see or hear me. He held Governor close to his chest, the trowel still poised above my brother’s head. His father lumbered over to be near his son. The mouth opened again, as if not wanting to miss even a drop of the baby’s blood.

Governor, who must’ve been oblivious to all this, looked up at my cousin, and what must Sumter have seen then?

But I knew, I felt it.

It was in the eyes.

Governor and Sumter, and me, and Grammy, and all the Wandigauxes—we had those same eyes.

We were the same blood.

We had come from the same flesh.

There was nothing to separate us.

“Dit-do,” Governor made his happy noise.

Sumter took the trowel and jammed it down and I screamed and jumped for him and the trowel went down easy into the spiny skin of the Feeder’s neck as it howled in pain.

Even Neverland could not make him hurt the baby.

The sea of ice was gone, and we were again on the island in Rabbit Lake.

The shadow that had been his father became part of the fog.

Sumter dropped the trowel and set Governor down on the damp grass.

Drops of blood on the trowel.

He had driven the trowel into his own stomach.

“Grammy.” Sumter’s eyes were bursting with tears, his face crumpled up, his nose runny; he himself sounded like a little baby. “Grammy, it ain’t my fault, it ain’t my fault.” He made croaking sounds, and I could not look at the gash in his stomach.

Grammy Weenie’s arms were outstretched for him. She sat up taller on the bank. “No, my baby, it’s not, it’s not.”

I rushed over and picked up Governor. He opened his small bean eyes and made his

dit-do

noise. I carried him back to the rowboat, setting him gently down, careful to keep his head up. “Grammy,” I said, “now we can go home. Sumter . . . ”

dit-do

noise. I carried him back to the rowboat, setting him gently down, careful to keep his head up. “Grammy,” I said, “now we can go home. Sumter . . . ”

For the first time I heard her voice in my head.

No, Beau. I love you, I love you all, I even love him, more now than ever, for his sacrifice. But where can we go? Neverland is only sleeping. It will awaken again when he has rested. You take your brother and go back

.

Where would this child be safe? Say good-bye to them for me, and forgive me for what I must do, and keep your brother from harm. If you live your whole life and that is the one thing you accomplish, it will have been enough.

No, Beau. I love you, I love you all, I even love him, more now than ever, for his sacrifice. But where can we go? Neverland is only sleeping. It will awaken again when he has rested. You take your brother and go back

.

Where would this child be safe? Say good-bye to them for me, and forgive me for what I must do, and keep your brother from harm. If you live your whole life and that is the one thing you accomplish, it will have been enough.

She held onto Sumter tightly.

“Hurts,” he was whispering, “hurts.” His hands clutched his wound.

Go

, Grammy’s voice commanded me,

go, Beau, go quickly.

, Grammy’s voice commanded me,

go, Beau, go quickly.

Sumter was crying, I know because I heard his small voice in my head as I rowed.

In my mind’s eyeball I saw: Grammy whispering to Sumter, “Close your eyes, my child. I’ll take you to a place beyond even Neverland, a place where we can all be together: you, Lucy, your mama and daddy, and me. All of us.”

“It ain’t Neverland?”

“It’s called Heaven, Sumter, and nobody ever gets hurt there, least of all you. We will go there together.”

The vision faded as she lifted her natural bristle brush in the air, turning it around so that the hard silver back was aimed for Sumter’s scalp, but I knew when she had brought it down because I heard a cracking noise and a gasp inside me, and it was the last time I would ever hear Sumter’s small voice in my head.

A fog in my mind enveloped them, and my grandmother was also dying,

willing

herself to die, but still holding her grandchild close to her breast so that their spirits might leave their cages of flesh together.

willing

herself to die, but still holding her grandchild close to her breast so that their spirits might leave their cages of flesh together.

Epilogue

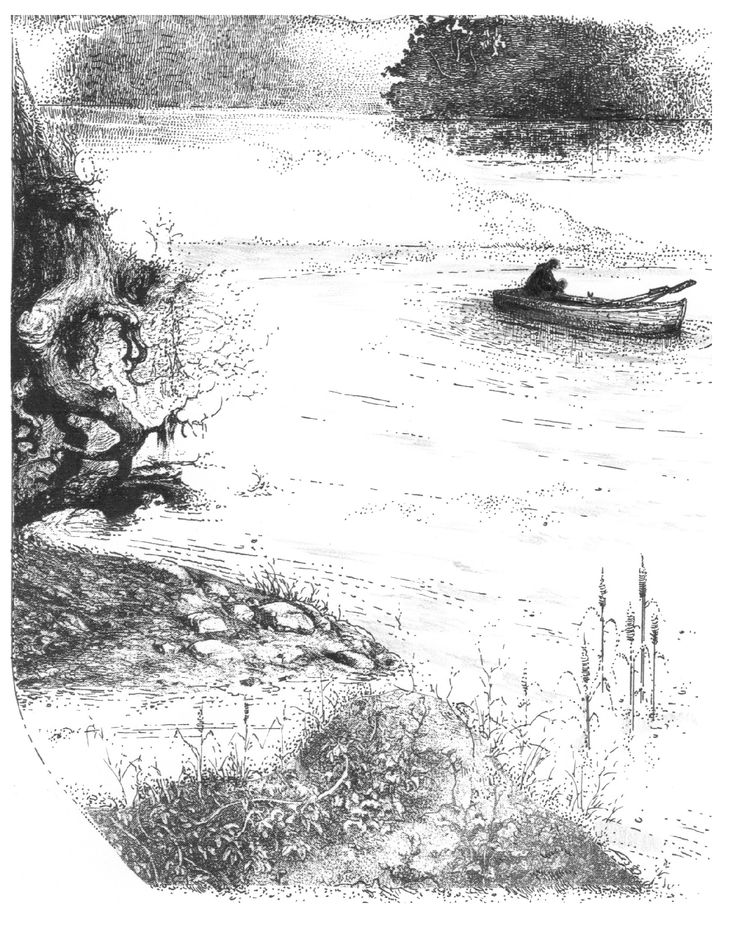

1I lay down exhausted, holding tight to Governor, and slept in the rowboat as the haze of fog engulfed us. The world seemed to have disappeared. We floated along into the emptiness.

I closed my eyes, feeling Governor’s steady breathing as I cradled him in my arms.

I dreamed, and in my dream I was still rowing, but out on the bay, and in my boat were my sisters and my mother. It was my version of Neverland.

My arms were tired from rowing, and the water was calm. I could not see through the fog and expected at any moment for a monster to come out of it and sink us. I knew I was dreaming, but there was a peacefulness to the dream. Mama was still sweating in her fever dream, but she held tight to my baby brother, who squealed happily at our adventure. Missy did not help with the rowing, but cried hysterically, her hands covering her face, and would not look up for one second, even when I told her it was all over.

Nonie said, “Do you think Daddy’s all right?”

I did not want to lie ever again

.

“Who knows?”

.

“Who knows?”

“I think he is,” she said, and seemed comforted by her own answer. “How long we been out here, you think?”

“An hour.”

“We headed out to sea?”

I shook my head. “We’re in the bay. We’ll get to land one way or another. If we were heading to sea, it wouldn’t be this calm.”

“I’m scared. We could die.” Missy whined.

“We won’t die.” I said, knowing this was the truth. My back ached and the small muscles in my arms felt like they were going to rip right off the bone. But I knew if I stopped rowing we would get nowhere.

“Is that the sun? Jesus

Gawd,

is that the

sun?

” Nonie pointed up, and son of a gun if it wasn’t the sun, and the white mist all around us was rending in two, painfully slowly the way clouds do, as if it hurt them.

Gawd,

is that the

sun?

” Nonie pointed up, and son of a gun if it wasn’t the sun, and the white mist all around us was rending in two, painfully slowly the way clouds do, as if it hurt them.

As I continued rowing, the sky, too, became visible: slate with clouds, but the sun was still there among them.

“Look!” Missy pointed off the starboard bow. “It’s there!”

The tiara bridge had not been washed out after all. It stood just as it had; someone had had the good sense to turn its lights on in the fog.

We still could not see land on either side of us, but I rowed, following the line of that bridge, knowing that one way or another we would reach the other side.

I looked forward and back, trusting we were heading toward the mainland.

“Daddy’s okay,” I told Nonie, “I know it now.” I didn’t say it just to make her feel better. I told my sisters that our father was there waiting at the end of the bridge because, through the fog, I saw his flashing headlights, our signal that he would not abandon us.

I awoke from this dream to see my father, half in the water, scrambling out to get the rowboat, with Julianne near him, calling to me, calling and laughing because the storm

was

over, the fog

had

lifted, and in my mind’s eyeball I’d pretty much gotten it right. Julianne shouted to me that my mama and my sisters were doing fine, that they were waiting for me back home.

was

over, the fog

had

lifted, and in my mind’s eyeball I’d pretty much gotten it right. Julianne shouted to me that my mama and my sisters were doing fine, that they were waiting for me back home.

My father came for us—he had gotten across despite the storm—and had not let even the fury of Neverland stop him.

I passed my brother to him.

He kissed the top of Governor’s scalp, and then mine, and he laughed, too, as if he could not withhold a surge of joy.

2Gull Island is still there off the Georgia coast, although it has been given a new name, and nice people with nice cars drive over the newly rebuilt tiara bridge to summer and winter homes.

The hurricane that swept across it the summer I was ten destroyed the older homes, including my grandmother’s. Trees were torn up at their roots.

There is still a bait shop, and even a semblance of the Sea Horse Amusement Park, although now it runs and has a low Ferris wheel rather than a roller coaster. Gullahs still live there, and if you were to ask them about that storm, they would tell you stories that would make your hair curl.

3I’ve always told anyone who asked that Sumter Monroe wasn’t really born bad, and I stand by that.

He’d inherited something—maybe just an imagination that was too big for his britches, and perhaps boys like that never do grow up. But nothing he ever did was just to be bad. Even trying to take Governor—at the last, I knew he wasn’t going to hurt my brother.

At the last, he had some sense.

Where is a child to go when the bridge is washed out

? Grammy had asked, and I won’t pretend to have an answer.

? Grammy had asked, and I won’t pretend to have an answer.

Some of us make it over that bridge that connects that island of childhood to the mainland where we all must go eventually, sometimes kicking and screaming. Yes, and sometimes we scream because we are alive.

I have watched my brother Governor grow up, and I have watched my parents divorce and find other mates and still fight the same fights they did with each other. I have watched while my sister told my mother off and never spoke to her again, and her twin made herself happy with a man who I could not stand to be in the same room with. She’s had five children with him. I have failed and succeeded at various careers and with various relationships. I have seen my cousin, my aunt, my uncle, and grandmother die, and did not feel grief until years afterward.

I have gone back and seen in my mind’s eyeball all that was and tried to change it, to fix it so it wouldn’t turn out so bad.

It’s important to me that things don’t turn out so bad.

I have tried, unsuccessfully, to exorcise the child who haunts me even to this day. He still waits on the other side of the tiara bridge.

Neverland

, he says,

where I am

.

, he says,

where I am

.

Perhaps we never cross that bridge completely.

But if childhood memory is filled with pain and nightmares, it is only memory, after all. It is not what lies ahead as we naviguess with sore muscles and tired hearts through white fog.

Copyright © 1991, 2010 by Douglas Clegg Interior illustrations copyright © 2009 Glenn Chadbourne

Published by Vanguard Press A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information and inquiries, address Vanguard Press, 387 Park Avenue South, 12th Floor, New York, NY 10016, or call (800) 343-4499.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clegg, Douglas, 1958-

Neverland / Douglas Clegg.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-593-15609-1

1. Boys—Fiction. 2. Islands—Fiction. 3. Family secrets—Fiction.

4. Demonology—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3553.L3918N’.54—dc22

2010002330

Vanguard Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail [email protected].

Other books

Critical Reaction by Todd M Johnson

A Forbidden Love (The Forbidden Series) by Niquel

Rain by Cote, Christie

Pennies For Hitler by Jackie French

Mr. Wham Bam by O'Hurley, Alexandra

Florida Straits by SKLA

I Didn't Do It for You by Michela Wrong

El Dragón Azul by Jean Rabe

Drawing the Line by Judith Cutler