Never Mind the Bullocks, Here's the Science (23 page)

Read Never Mind the Bullocks, Here's the Science Online

Authors: Karl Kruszelnicki

After all, the electric field from the Sun is about four times greater than that from a mobile phone, or 200-400 times greater than that from a mobile phone tower.

Cause of Petrol Station Fires

So what did set off those 243 petrol station fires? Most of the time, static electricity was the culprit.

We have all seen or felt a spark from clothing. If you are wearing synthetic clothes in the dryness of winter, and are sliding in and out of the car, across the synthetic material of the car seat, then you can build up a big static charge. Then, if the earthing wire on the petrol hose is broken, when you touch the metal nozzle of the petrol hose to the metal neck of the petrol tank, you can discharge a visible spark. If you are very unlucky, the petrol vapour around the open petrol tank is in the range of 2-8% by volume. If you are extremely unlucky, the spark happens in a ball of this petrol vapour, which could explode. This has happened.

From the static electricity point of view, filling up a small fuel drum (either metal or plastic) on the back of a pick-up truck is even more dangerous. The friction between the truck and the container can build up enough energy to generate a static electricity spark. This has also happened.

Why the Petrol Station Warnings?

The phone companies post warnings about using mobile phones in petrol stations for two reasons.

First, mobile phones are not designed with ‘Intrinsic Safety’ to make them able to operate safely in truly hazardous inflammable vapour situations. Second, mobile phone manufacturers are afraid

of legal liability, despite all the evidence showing that mobile phones have never caused a fire in a petrol station.

So overall, the mobile-phone/petrol-station-fire myth is just endless chatter generating a whole lot of static.

New York Static Electricity

In the late 1970s, I was doing research into picking up electrical signals from the human retina (this was to diagnose certain eye diseases, such as Retinitis Pigmentosa). I spent three months working on this at the Columbia Presbyterian Physicians and Surgeons Hospital in New York. I stayed in the 13-storey nurses home. It was winter, and very dry.

In the mornings, at the elevators, everybody would wait for someone else to be the first to reach out and touch the metal elevator call button. The reason was that we had all built up lots of static electricity just by walking down the corridor from our rooms, and we would generate a painful 2 cm electrical spark as we reached out to the metal elevator call button.

I always wore T-shirts during my stay there. And at the end of each day, when I went to my tiny room, I would take off my T-shirt and throw it onto the bed. The static electricity would keep it from collapsing for about 15 minutes. I didn’t have a TV, so it gave me lots of free entertainment watching it slowly collapse as the static electricity drained off.

References

Jennings, Bob, ‘Big bang theory’,

Sydney Morning Herald

, 30 December 2005, p 4.

Mikkelson, Barbara and David P., ‘Fuelish pleasures’, 12 November 2006, http://www.snopes.com/autos/hazards/gasvapor.asp.

Schwartz, Ephraim, ‘Mobile battery problems explode: experts ponder alternatives to batteries that have caused fire in notebooks, cell phones’,

PC World

, 22 December 2003.

Suzuki, Hiroshi and Eki, Yoshinori, ‘Nokia voluntarily recalls 46 million cellphone batteries’,

Washington Post

, 15 August 2007.

Virki, Tarmo, ‘Nokia warns consumers of battery overheating risks’,

Washington Post

, 15 August 2007.

*

Conflagration is an uncontrolled burning that threatens human life.

An integral part of many Hollywood movies is the gratuitous car chase. This is a way of padding out the movie, without actually having to write additional intelligent script, or advance the plot. An important part of the car chase is the car exploding as soon as it runs into another vehicle or goes over a conveniently placed cliff. In fact, the opposite is true—it is surprisingly difficult to get a petrol tank to explode and blow up a car.

Petrol 101

The liquid which is called ‘petrol’ in the UK and Australia is known as ‘gasoline’ in the USA. The word ‘petrol’ originally referred to the oil that came out of the ground. The term was first used in 1892 to refer to the refined liquid that you can put into an internal combustion engine. In the early days, before petrol stations existed, it was sold from chemists in bottles. It was used as a dry-cleaning fluid to remove oil stains from clothes, and to treat human hair against lice and lice eggs.

Water is a liquid made from a single chemical, H

2

O.

Petrol is completely different. It’s made from many different liquids, and the ratio of these constituent liquids varies widely depending on various factors. Volatility—the ability of a

substance to change from a liquid into a vapour—is one of the many factors. In a cold climate, the petrol should be highly volatile, so that the engine will be easy to start. However, in a hot climate, if the petrol is too volatile, it can turn into a vapour while inside the pipes carrying the petrol from the fuel tank to the petrol pump. The pump cannot pump vapour, so the engine stops—this is known as ‘vapour lock’.

Petrol can be made from toluene (up to 35% by volume), xylene (up to 25%), methyl tertiary butyl ether, or MTBE (up to 18%), trimethylbenzene (up to 7%), benzene (up to 5%), naphthalene (up to 1%), and ten or more other ingredients. To look at it another way, petrol is mainly a complicated blend of paraffins, naphthenes and olefins. Of course, alcohol, detergents, anti-corrosives, combustion improvers, reducers of internal carbon build-up, octane improvers and lubricants can also be added.

The ratio of the various chemicals depends on climate, the particular oil refinery and its capabilities, the needs of the consumers, local laws (e.g. the percentage of ethanol that must be added), and so on.

Lights, Camera, Boom

An important part of a movie car chase scene is the car exploding as soon as it runs into another vehicle, or goes over a conveniently placed cliff. In fact, the opposite is true—it is surprisingly difficult to get a petrol tank to explode and blow up a car.

Petrol, the liquid, will not burn.

The oxygen in the atmosphere can’t get at enough molecules in the petrol to react with them and provide a fast chemical reaction. But the vapour is ‘thin’ enough to spread widely over a large volume of air and reach lots of oxygen. So what burns is the vapour that comes off the petrol.

Hydrocarbons

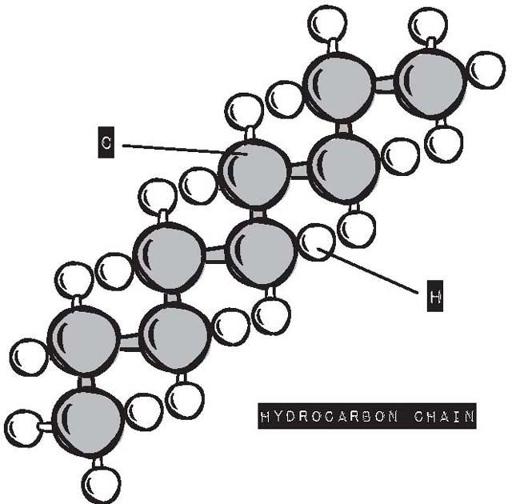

The liquids that make up petrol have one thing in common. They contain hydrogen and carbon—in other words, they are hydrocarbons.

As far as the oil industry is concerned, the lovely thing about hydrocarbons is that they burn, giving off energy.

The hydrogen (H) in the hydrocarbon burns with oxygen (O) to give water (H

2

O) and lots of energy.

2H

2

+ O

2

→ 2 H

2

O + energy

The carbon (C) in the hydrocarbon burns with oxygen (O) to give carbon dioxide (CO2) and lots of energy.

C + O

2

→ CO

2

+ energy

When oil comes out of the ground, it contains lots of different hydrocarbon molecules—some of them with hundreds of carbon atoms all joined together in a long chain. The good thing about long hydrocarbons is that they give up lots of energy. The bad thing is that long hydrocarbons are hard to start burning. Therefore, in an oil refinery the long hydrocarbons that come out of the ground are broken down into smaller hydrocarbons for your petrol tank.

In petrol, most of the hydrocarbon molecules that burn easily have between 4 and 12 carbon atoms. This range gives a good mix of easy burning and lots of energy.

Hydrocarbons

The liquids that make up petrol have one thing in common.

They contain hydrogen and carbon – in other words, they are hydrocarbons.

As far as the oil industry is concerned, the lovely thing about hydrocarbons is that they burn, giving off energy.

The hydrogen (H) in the hydrocarbon burns with oxygen (O) in the air to give water (H

2

O), and lots of energy.

The carbon (C) in the hydrocarbon burns with oxygen (O) in the air to give carbon dioxide (CO

2

), and lots of energy.

Hydrocarbons consist of a ‘backbone’ or ‘skeleton’ composed of carbon and hydrogen.

Liquid Petrol Does Not Burn

Now here’s the tricky part.

Petrol, the liquid, will not burn.

The oxygen in the atmosphere cannot get at enough molecules in the petrol to react with them and provide a fast chemical reaction. But the petrol vapour is ‘thin’ enough to spread widely over a large volume of air and reach lots of oxygen. So what burns is the vapour that comes off the petrol.

And now it gets even more tricky.

If you fill the cabin of a car entirely with petrol vapour, it won’t burn—because while there’s a lot of fuel, there’s no oxygen to burn the fuel. So petrol vapour at 100% concentration won’t burn.

Suppose you go to the other extreme and fill the cabin of the car with 0% petrol vapour and 100% air. Obviously, it won’t burn, because there’s no fuel.

But there is a percentage at which petrol vapour will burn, somewhere between 0% and 100%.

In most cases, in most climates, petrol vapour will burn only when it makes up between 2% and 8% of the volume, with the air making up the rest. (The exact concentration varies—other sources quote 1-6%.)

It’s not that easy to get petrol vapour in a range of between 2% and 8%. This means that exploding fuel tanks are not very common.

Pinto Burned Too Well

In today’s cars, the petrol tank is usually housed deep between strong lumps of steel, that are also structural members of the car. They protect the petrol tank in the event of a collision.

But one particular small 1970s American car, the Pinto, suffered from two very bad design faults. As a result, it could burst into flames when hit from behind.

First, the pipe that joined the petrol cap to the petrol tank would easily tear loose in a rear-end collision. If the Pinto were to tip over, raw petrol could pour onto the ground from the open tank.

Second, the petrol tank was immediately behind the differential—that big ‘pumpkin’ of metal in the middle of the back axle. The distance between the rear bumper bar and the fuel tank was only about 20 cm. Unfortunately, the rear bumper had no structural integrity and was just an ornament. In a rear-end collision, the petrol tank would get squashed against the differential, and could split open. Again, this meant that liquid petrol could spill out onto the ground.

(It didn’t help that the body of the Pinto was poorly reinforced. In many accidents the doors jammed shut, making the Pinto a death trap.)

All that was needed for a fire was a spark—from bare electrical wires, or from metal parts scraping on the road, or against each other. If a spark were to occur where the petrol vapour level was between 2 and 8%, the vapour would ignite and explode.

According to the news media, about 500 people died, and another 400 were badly burnt, as a result of petrol fires caused by

rear-end collisions in Pintos. However, according to a more sober analysis by the lawyer Gary T. Schwartz in the

Rutgers Law Review

, the Pinto was typical of similar cars of the time (1970s), which were all pretty ‘unsafe’ when compared to today’s cars. He also argued that the number of deaths was closer to 27 than to 500.