Never Be Sick Again (4 page)

Lying on what had been pronounced my deathbed, I thought about Cousins's book in relation to my graduate school days doing scientific research at MIT. I wondered how Cousins managed to find the pertinent information he needed to save himself. If Cousins, a dying man with no scientific training, could obtain such critical, life-saving knowledge, why couldn't his physicians? After all, these professionals had devoted their entire careers to medicine. Knowing that Cousins had found a way to save his own life encouraged me; I hoped that my scientific training as a chemist might enable me to do the same.

As I lay there with a poisoned liver, dying from chemical hepatitis, I realized that if I wanted to live I must act quickly. Not much time was left. Thinking about how instrumental vitamin C was in Cousins's recovery, I remembered from my study of biochemistry that vitamin C plays an essential role in liver detoxification. Because my liver had been poisoned by a toxic drug, perhaps some vitamin C would help it detoxify. It seemed like an experiment worth doing, and besides, I knew of no other options.

It worked.

Twenty-four hours after starting oral doses of vitamin C (about four grams a day), my vital signs began to stabilize. In forty-eight hours I was able to sit up in bed. A few days before, death had been a certainty. Now, I could sit up, which was the first time I had experienced a measurable improvement in all those months. Progress, even in the form of something as simple as sitting up in bed, can be incredibly inspiring. At that point, I knew I could take action that would make a difference. Meanwhile, my physicians could not understand why I not only survived but actually improved.

I was still far from well, though. I was a frail skeleton. I had difficulty performing the simplest tasks, such as dressing, or tying my shoelaces. I had no energy and became fatigued from the slightest exertion. My hands and feet were numb; I had difficulty walking and moved slowly. I was lightheaded and tended to fall over easily. Worse, my brain had trouble functioning; I felt like I was in a mental fog. I had difficulty with short-term memory and simple calculations. Even as I improved enough to venture out again, I could not make correct change at the grocery store and easily forgot what I intended to do.

Perhaps worst of all was the horrific chemical sensitivity that I continued to suffer, causing me to become weak, disoriented and debilitated. The toxic assault on my body by the metronidazole had left me with acute chemical sensitivities. For instance, when I turned on a water faucet the subtle chlorine fumes coming out with the water were enough to cause me to become weak, lightheaded and disoriented. I could not read or be near printed materials because of the chemical fumes coming from the ink and paper. I used only a speakerphone because I would react to the fumes off-gassing from the plastic telephone receiver. My gas water heater had to be replaced with an electric unit because I reacted to the combustion fumes diffusing into the surrounding living space. I had to wear clothes made only from natural fibers, to avoid the toxic fumes from synthetics. I had to purchase special water and air filters. But even with these many precautions, I was debilitated by my relentless reactions to a myriad of environmental chemicals.

Someone who has not personally experienced chemical sensitivity has a hard time understanding how just a whiff of certain chemicals can create total havoc in a matter of seconds. I remember once taking a piece of Scotch tape off a roll and being devastated for the rest of the day by the seemingly inconsequential chemical odor from the tape! With chemical sensitivity, the nervous system develops a “memory” of past reactions. This effect is called

classical conditioning

(i.e., biological learning) and upon detecting these reactive agents again, even in infinitesimal quantities, a full-scale response is produced. Our modern world is permeated with chemicals that can produce such reactions in susceptible people.

In this hideous state of health, I fell into a deep depression. I thought about taking my life. Although I had made some progress, I was allergic to almost everything, and I was in a constant state of debilitating reactions. My life was ruined. No doctor could help me. I was unable to do any meaningful activity and had nothing to look forward to. I could not even watch television because of the chemical fumes off-gassing from the TV set as it heated up.

Choosing to Live

One beautiful afternoon, I was sitting out in the sun and contemplating the meaning of life. Illness has a powerful way of providing perspective and time to think about the really important things. I asked myself whether or not I wanted to continue living. I decided that I did not want to dieâI wanted to live. However, life was not worth living in such a debilitated state. My only option was to find a way to become healthy again.

How could I do this? The doctors could not help. In large measure, doctors had brought me to my failing condition. I recall thinking about the explosion of knowledge in the worldâabout all the new scientific data being published every day. Surely somewhere, some key bit of information would help me. I became determined to find out whatever I could, but it was not easy. My vision was blurred and my eyes hurt. Given that I was unable to be near printed materials because of the ink fumes, how could I study? My mind didn't work right, either: Contemporary literature about chemically sensitive people describes this debilitating type of “brain fog.” In my early quests to research my health condition, I would find myself lost in a mental fog, spending hours reading the same material repeatedly without realizing it. Ironically, I was reacting to the very materials I was using to learn how to restore my health.

Still, I remained determined. I purchased a respirator mask to protect me from the chemicals coming from the ink in my study materials. Unfortunately, the rubber part of the mask gave off toxic fumes. I took the mask apart, boiled the rubber pieces in water for two days and then reassembled it, which made the mask tolerable so I could wear it while I did the necessary work.

Next, I purchased a portable electric oven and one hundred feet of outdoor extension cord. I placed the oven downwind from my house and baked all of my reading materials in order to drive off the ink chemicals. Bizarre, but it worked. Now at least I could handle and read my rapidly accumulating piles of medical and scientific literature. I began to educate myself, looking for clues that might help to restore and improve my health.

Thus began a new phase of my life, which continues to this day.

I came across fascinating information as I searched for the answers to my questions. I read technical papers written by a biochemist who, like myself, had become chemically hypersensitive. No physician had been able to help him either, and his sensitivity was so great that he was forced to move to a distant location that harbored no man-made chemicals. He moved into a small wooden shack on a remote beach. Eventually, through his understanding of biochemistry, he was able to take steps to restore his health.

Knowing that someone else had been able to heal himself of this horrendous condition gave me the hope I needed so much. His example convinced me that I, too, would be able to help myself to understand the biochemistry of my illness and apply sound scientific principles to solve my problems. It took me two years of learning and experimenting to raise myself from the depths of liver failure, chronic fatigue, autoimmune diseases and chemical hypersensitivity. Recovery took a great deal of persistence, willingness to try new things and acceptance of many setbacks.

In particular at the height of my chemical sensitivities, I had to be extremely careful about the products I selected. Even minute amounts of toxins were enough to make me ill. I ended up with a kitchen full of vitamin supplements that I could not take because of toxic impurities and my level of susceptibility. Even healthy people are harmed by these impurities, though it may not be as evident to them.

I learned the hard way how suffering can come when health is failing, and when you try remedies that do more harm than good. Even with my scientific training, finding the answers was difficult. Particularly with vitamin supplements and personal care products, a great deal of conflicting information abounds, and consumers remain confused about how to make the best choices. Accurate health information is in great demand, and that is precisely what this book provides. I want to share what I have learned about getting well and staying well.

In 1991, I resigned from all my business and community activities and devoted myself to teaching others how to be healthy. I started by speaking to groupsâat first, the same support groups to which I had belonged during the depths of my illness. Then I branched out with a wider audience, which evolved into a regular evening workshop series that continued for years. Later, a publisher became aware of my work and invited me to write a column for his newspaper. After that, I started a radio show called

An Ounce of Prevention

and began publishing my own newsletter,

Beyond Health News.

This book is the next step.

Reaching Our Potential

One of the most profound conclusions I have reached is that

health is a choice;

virtually no one ever has to be sick. The potential for human health and longevity is far greater than we are now achieving. Scientific studies describe populations who lived longer and healthier lives than we do, simply because their societies made dietary and lifestyle choices that supported human health. With just a little knowledge and effort, we can do the same. We can choose health, but first we must educate ourselves.

My own quest for an understanding of how the body maintains and heals itself continues to this day. Throughout my research, I continue to ask myself basic questions, such as:

⢠What is health?

⢠What is disease?

⢠Why do people get sick?

⢠How can disease be prevented or reversed?

⢠How long can people live in good health, and what does it take to achieve this?

⢠What is the potential for human health and longevity?

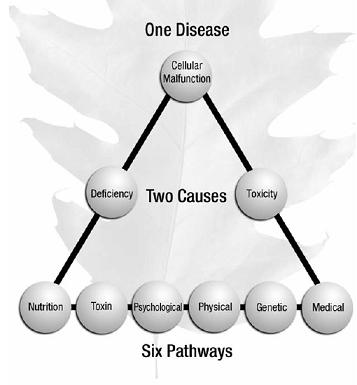

Please allow me to pass on to you a truly revolutionary theory of health and disease, one that is so simple and powerful that it gives you the choice to never be sick again.

“There is no reason in the world why over 75 percent of the

American people should be suffering from degenerative and

deficiency diseases. Disease never comes without a cause. If

a person is sick and ailing it is because he has been doing

something wrong. He needs an education in how to live a

healthy life.”

Jay M. Hoffman, Ph.D.

Hunza

M

ost people expect to be sick at least one or more times each year, to cope with at least one serious illness by midlife, and in all likelihood, to die of one or several diseases by their eighties, if not sooner. Most people also think poor health is mainly the result of bad luck and that their longevity is a matter of good fortune.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Poor health is not a matter of luck; poor health is a matter of choice. We do not “get” sick. We make ourselves sick by making bad choices and, conversely, we get healthy and stay healthy by making good ones. Most people feel that they are “healthy” as long as they have no symptoms of disease. Few people realize what optimal health really feels likeâand even fewer accept the notion that a vigorous and healthy life beyond 100 years old is within reach. In reality, that kind of long life is what we should all routinely expect.

Meet the face of optimal health. His name is Jose Maria Roa, and he is 131 years old. Jose lives with his family in a small village, high in the Andes Mountains of Ecuador. While his face is weatherworn, his mind is keen, his heart is healthy, his teeth are strong and the lines around his face are born of smiles and the joy of a loving wife and family. Still working on his small farm every day and enjoying an active sex life, Jose fathered his last child at the age of 107. When asked if he'd ever been sick, he replied, “Yes, I have been.” Jose had a few coldsâthat's itâin 131 years! Until his death at 137, Jose remained in perfect health.

Surely this is not normal. Isn't Jose a medical miracle, an aberration of nature? Not so. In his remote village, Jose's health and longevity are far from unusual explains Morton Walker, D.P.M., whose 1985 book

Secrets of Long Life

is based on his study of these hardy people native to the Vilcabamba Valley. For instance, in his queries to the Vilcabambans about the mental health of their society, Walker asked if the older people suffered memory loss due to dementia. These long-lived people had never experienced anything like dementia. They didn't understand the question and, in fact, did not even have words in their language to describe such a condition. Meanwhile, we are told that dementia is a disease of aging and the price we must pay for our so-called “longevity.” As I studied Joseâand people like himâI began to understand the potential that all humans have to be healthy.