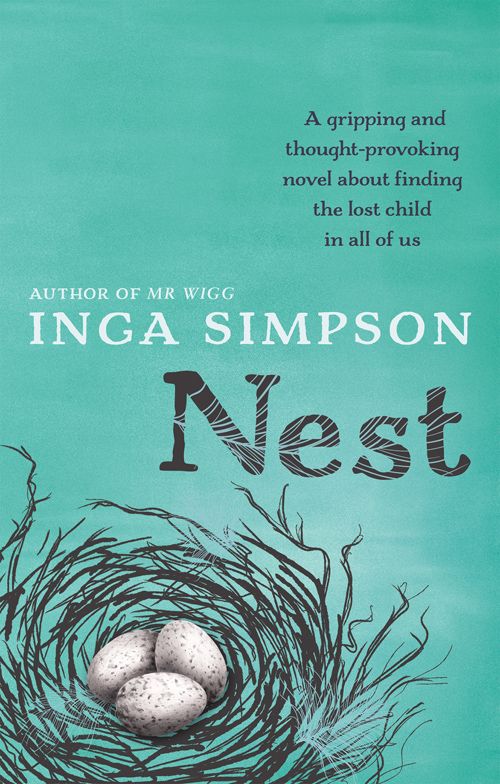

Nest

Authors: Inga Simpson

Mr Wigg,

also by Inga Simpson

‘a tender story’

Country Style

‘beautiful and absorbing’

Sydney Morning Herald

‘a contemplative story that will touch your heart’

Marie Claire UK

‘resonantly powerful at every bite … Just beautiful.’

The Australian Women’s Weekly

‘Beautifully crafted and brimming with warmth.’

Who Weekly

‘

Mr Wigg

captivates to the end.’

Good Reading

‘A sense of what is right and good about the world overwhelmed me on closing this book.’

Books+Publishing

‘Inga Simpson gives readers a character so realistic … that it’s hard to believe he’s a work of fiction.’

Herald Sun

‘captures the pleasures of a simple country life’

Vogue Australia

Mr Wigg

was shortlisted for the Indie Awards 2014

For Nike

Praise for Mr Wigg, also by Inga Simpson

The character study of the bird is beyond the mazes of

classification, beyond the counting of bones, out of the reach

of the scalpel and the literature of the microscope.

Mabel Osgood Wright,

The Friendship of Nature

Yellow

YellowS

he was trying to capture the wild. The secret to what made it unique and other. She had been trying her whole life.

Today it was the eastern yellow robins bathing. Of all the birds, they were the most ridiculous, pitching chest-first into the water and shaking themselves into fluffy rounds until their eyes and legs disappeared. Even with the softest pencil, she couldn’t achieve the same effect on the page.

The more brazen yellow of Singapore daisy – on the run at the edge of the lawn – occupied her peripheral vision, reminding her of all the things she should be doing now the weather had cooled.

She had forgotten, during the years she had been away, how much work a property was in this climate. There was always something needing her attention, which was fine with her most days; it wasn’t as if there was anyone else to give it to.

‘We get our hundred inches a year,’ the agent had said, not realising she knew the majority of it came down over one or two months in summer, which, while keeping everything green and lush outside, also turned every formerly living thing

inside – wood, leather, cane – green with mould. The sheer volume of water washed away driveways and vegetable beds, submerging roads and train lines. All the same, there was something satisfying about living in a place where you could still be cut off from the world. And autumn, winter and spring were close to perfect.

The trees gathered round, their trunks a steady grey-brown. Sometimes she suspected they shuffled closer during the night, just an inch or so, rearranging their roots around rocks and soil. In the morning sun, shafting down from the ridge, their new leaves were luminous, as if emitting a green light of their own. The robins made the most of it, their chests and rumps flashing a complementary yellow as they darted for insects.

Her tea had gone cold. Life’s pace had slowed, living among trees again, and she had been happy to let it.

S

he heard the spray of gravel at the top of the driveway and the car door. Three-fifteen already. She left the pile of weeds where they lay, washed her hands under the garden tap, and made it inside in time to hear the thud of Henry’s bag at the front door before he removed his shoes.

‘Hey.’ Red-rimmed eyes suggested he hadn’t had a very good day.

‘Hey,’ she said. ‘I’ve set us up out the back.’ She put the kettle on and sliced two pieces of banana cake, sniffed at the neck of the milk carton. She didn’t drink it herself and it never seemed to last long.

The boy’s visit cut a notch in the week. Without it, without Henry, time tended to stretch to the point that she was no longer part of its passing. He anchored her to the world outside.

She carried out the tea and cake in two trips. ‘You right to keep going with the movement piece?’

He shrugged. Set out his sketchbook and pencils.

‘How was school?’

‘Haven’t you heard?’

‘Heard what?’

He shook his head. ‘You don’t even listen to the radio?’

Sometime during her first year, she had stopped playing her steel-stringed rock albums and dropped back to folk and indie. By her second winter, she found that only classical music, which she had not often gone to the effort of playing before, didn’t seem out of place. The birds moved in sympathy with cello and violin, and the trees dipped their leaves in time to piano. When she tired of all her CDs, she just left the radio on Classic FM, which included news at regular intervals, and interviews with artists and musicians that were sometimes interesting. But then the voices of the announcers, and the inevitable opera sessions, began to grate – and frightened off the birds. Now, into her fourth year, she preferred silence. Or, rather, the forest orchestra of bird, frog and cicada.

It was a hazard, though; nothing attracted greater scorn from children than not being up with things. You could lose all credibility in a moment. ‘What’s happened?’

‘Caitlin Jones is missing,’ he said. ‘She walked home from school the day before yesterday but didn’t make it.’

‘Where does she live?’

‘Annies Lane.’

‘That’s a bit far to walk.’

‘She normally gets picked up. Her father had car trouble,’ he said. ‘Someone saw her near Tallowwood Drive but nothing after that.’

Jen blew steam off the dark surface of her tea. ‘This was all on the news?’

‘It is now. They told us at school this morning. The police were there when Mum dropped us off, keeping the reporters away. And they got a counsellor in.’

Jen held her cup against her chest. A treecreeper’s claws scritched on a bloodwood, securing its hopping, vertical ascent.

‘She’s in your class?’

‘Yeah.’

‘That’s awful,’ she said. There were no longer any tallowwoods on Tallowwood Drive; council had made sure of that. Last summer, someone had taken the corner too fast and run their car into one of those old trees. The whole lot had been removed, thirty lives in exchange for one. It wasn’t far from Slaughter Yard Road, which she had thought appropriate at the time. Now it didn’t give her a good feeling. If the counsellor had been brought in, the police probably didn’t have a good feeling about it either. ‘Any other brothers or sisters?’

‘A sister,’ he said. ‘In grade four. Briony.’

‘I’m sorry.’ What were you supposed to say? What was she supposed to say, the non-parent adult, the non-teacher? ‘I hope they get to the bottom of it soon.’

The boy opened his sketchbook.

‘C’mon,’ she said. ‘That cake’s still warm from the oven. See if you can do it some justice.’ She adjusted the wooden mannequin till it was sprinting, knees high, arms pumping. It was an antique she had picked up in a store down south, run by a mad Frenchman who felt obliged to comment on customers’ poor taste and general ignorance if they were silly enough to ask for something he didn’t have.

Henry lifted the wedge of cake to his mouth, disappearing almost half of it in one bite.

‘Remember we’re just going for impressions, getting that sense of movement.’

He took a gulp of his tea and selected a 2B pencil. Swallowed.

The afternoon light caught all the cobwebs she should remove from the deck railings. Snagged on leaves or floating free on the breeze, they were gossamer silver, part of the forest’s magic. In the house, they were a damn pain. They appeared overnight, linking beams, rafters and lights. If you sat still long enough in autumn, you’d find yourself the corner post for a spider’s lair. It drove her crazy if she looked too hard.

The boy’s lines were good: no hesitation, not too much confidence. His technique was self-sown, with a few little habits that needed undoing. But he had a style of his own, and was interested. That’s all that mattered at this point. He didn’t look up, just drew and chewed.

He seemed all right, but you never knew what was going on beneath. She had been teaching him for three months and still didn’t feel as if she had any sense of his hopes and dreams.

‘That’s good,’ she said. ‘Get some life in those legs.’

Henry wasn’t quite nailing it. Her first teacher had always claimed he could judge her mood from her work. Perhaps there was something in that – and who could blame the boy today? ‘What’s the biggest muscle in the human body?’

His pencil paused. ‘Thighs?’

‘Well, there are two muscles there, the quadriceps and hamstrings. And together they are very powerful, and essential for running. But it’s our buttocks, gluteus maximus, that are the biggest. That’s where your runner’s power is coming from – you need to think about the force of the movement, as well as the direction, to get your line of action.’