Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight (11 page)

Read Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #Science, #Astronomy, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology

The boss, chief X-15 test pilot Joe Walker, was flying chase. Neil radioed him, “I have south lake in sight, Joe.”

Joe Walker came back, “What’s your altitude, Neil?”

“Got 47,000.”

NASA One joined in. “Yes, we check that,” confirmed flight control. “Have you decided what your landing runway is yet?”

Neil checked the ground beneath him. All he could see was desert and Saddleback Butte to his right. “Let me get up here a little closer. I can definitely see the base now,” he told the flight center.

Suddenly Neil had his own cheering section. “He’s going to make it,” said one flight controller.

“I’ll bet you a dollar he doesn’t,” said another.

“You’re on.”

“We show you 26 miles to the south lake and have you at 40,000,” NASA One reported.

“Okay,” Neil acknowledged, as he got busy ridding his X-15 of useless things that added weight and cut down his gliding distance. When he was done he keyed his mike and told flight control, “The landing will be on runway 35, south lake, a straight-in approach. I’m at 32,000, going to use some brakes to put her down.”

Using speed brakes to reduce energy confirmed that Neil’s return to south lake could not have been as close a call as some had thought, and the research test pilot, the calmest hand around, lined his X-15 up for a safe touchdown.

“I’m about 15 miles out from the end now,” Neil told the center. “I’m 290 knots.”

Neil opens his X-15’s canopy with a smile. (NASA)

Fellow test pilot Henry Gordon was flying chase, too. He called Neil, “I’m coming up on your right.”

“Okay,” Neil acknowledged Henry. “I’m going to land in sort of the middle of the south lake bed,” he told Gordon. “Brakes are in again, 280.”

“Rog, start your flaps down now,” Henry told him.

Neil’s X-15’s approach was as smooth as an Eagle gliding on mountain currents.

“Okay, you’re well in,” Henry told him. “Go ahead and put her down. The rocket glider made not a sound as it touched desert and Henry said, “Very nice, Neil.”

And it was very nice. Neil Armstrong brought his X-15 in so smoothly its nose wheel barely kissed dry desert before rolling to a textbook stop.

Neil had just racked up the X-15’s longest endurance mission (12 minutes, 28 seconds), and the longest distance flight (350 miles, ground track) a project record.

Could there be any more questions about Neil’s ability to fly?

We think not.

Neil Armstrong ready to be an astronaut. (NASA)

SIX

TRAINING DAYS

Project Mercury moved forward with the launch of Scott Carpenter. It was the project’s second orbital flight, while back at Edwards Neil Armstrong waited. He was staring at the phone when it finally rang.

“Hi, Neil, this is Deke. Are you still interested in the astronaut group?”

“Yes, sir,” he assured NASA’s director of flight crew operations.

Deke was another man of few words. “Well, you have the job, then,” he told Neil. “We’re going to get started right away, so get down here by the sixteenth.”

“Yes, sir, I’ll be there.”

Neil and eight others had been called by Deke. They would be announced as the Gemini Nine. Neil traded in his two cars for a used station wagon. He needed the larger vehicle to haul the family’s personal belongings. He and Janet packed up the big stuff and furniture and shipped it ahead for storage in Houston.

There were still loose ends to be tied up so Janet stayed behind a couple of days.

Neil took Ricky with him in the station wagon, and two days later Janet took a commercial flight. She arrived in Houston the same day as Neil and Ricky and for the next few months the Armstrongs would live in a furnished apartment. They were waiting for their new home to be completed in the El Lago subdivision—a housing project built to attract astronauts. It was only a few minutes from Neil’s new office.

The Gemini Nine were officially announced as NASA’s second group of astronauts September 17, 1962. They were Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Charles “Pete” Conrad, James Lovell, James McDivitt, Elliot See, Tom Stafford, Ed White, and John Young. Some would become legends. Some would give their lives. None would be forgotten.

Neil thought of his group as answering the call for volunteers to fly to the moon. Their predecessors, the Mercury Seven, had been remarkable in converting “Spam in the can” to a successful human space program.

What NASA had in the Gemini Nine were test pilots, well-educated and experienced for the job. What Neil saw was

passion,

like most early NASA folks who were willing to work their tails off.

Deke Slayton now had fifteen astronauts under his wing. He set the new pilots up for indoctrination and training, and figured the more they saw of the remaining days of Project Mercury the better prepared they’d be for flying the heavier, larger, advanced Gemini. The Nine would be the ones to develop the flight maneuvers and procedures needed for that bridge to the moon.

Then, on October 3, 1962, the rookies gathered at the foot of the Mercury-Atlas launchpad. They watched Wally Schirra and his

Sigma 7

spacecraft thunder into orbit. The Nine hung onto every report from Schirra as the Mercury astronaut displayed his skills. The third American to orbit Earth stayed up for six orbits—nine hours—moving through his scientific and engineering checklist with an efficiency that would turn a robot green with envy.

The Gemini Nine were so impressed with Wally’s flight they eagerly jumped into their grueling tour of Gemini’s contractors. They spent weeks getting acquainted with where and how their Gemini spacecraft and Titan II rockets were being built and tested. Once they had an educated feel for the hardware they would fly, they settled in for their individual training program.

The good news was training for the Gemini Nine wouldn’t be anything like that endured by the Mercury Seven.

They wouldn’t have to drop their pants and sit on a block of ice and whistle while eating saltines. They wouldn’t have to be stripped of all noises and sit in a soundproof room hearing only their hearts pounding.

“I don’t think the community of flight medicine and flight physiology knew very much about what they needed at the time,” Neil would tell me, adding, “There were widespread predictions that humans could not survive in space—for all kinds of reasons. I think they tested for everything, missing nothing,” he grinned, asking, “Have you ever felt the need to hold a full enema in your colon for five minutes?”

We laughed and Neil had one more thing to say. “It was not fun.”

* * *

Armstrong was content to spend his astronaut learning days with familiar exercises he’d experienced in naval flight training as long as he could study at night. “NASA felt we should know the difference between an aircraft and spacecraft,” Neil explained, “especially what made you stay in orbit.

“I had studied orbital mechanics at the University of Southern California, and none of us found the new studies a burden.”

They hit the books, and along with academics Neil and his group were called out for a number of other training disciplines.

To make sure they knew how everything worked, the Gemini Nine spent time crawling over and under Cape Canaveral’s launch facilities in Florida. The bosses thought it would be good if they learned how rockets and spacecraft were launched, and how to get off of one of the damn things if there was a problem. They learned that, too, but first they had to learn how not to disturb the rattlesnakes and feral razorbacks that had made much of the launch complexes their home.

Then, when they had launchpad etiquette down, they returned to Mission Control, Houston, to learn how they would be tracked and watched over in flight.

But no sooner than they were used to sleeping in their own beds again, they were off to Johnsville, Pennsylvania, to the Navy’s Acceleration Laboratory to ride the “Wheel.”

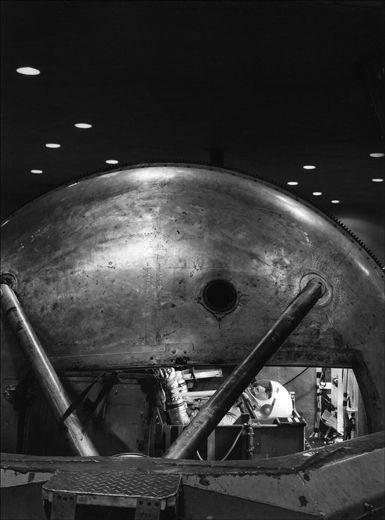

The Wheel was a huge centrifuge with a gondola, a mockup of the Gemini cockpit. This is where the astronauts experienced simulated reentries from Earth orbit. During these centrifuge runs, doctors would monitor them on closed-circuit television—one run simulated a G-pulling steep reentry. Neil was ready for this. None had anything close to his experience riding a centrifuge. When Neil felt the force of tremendous deceleration, he was able to keep moving his arms and legs until he approached 10 Gs (ten times his own weight). And as the g-forces mounted, his eyeballs flattened out of focus. When the centrifuge passed 15 Gs, Neil could no longer breathe.

The centrifuge wheel ridden by Armstrong. (Johnsville Centrifuge, NASA)

For jungle survival training in the Panamanian tropical rain forest, Neil and John learn how to build a dry floor for their survival hut. (NASA)

The operators stopped the damn thing and Neil stepped from the gondola. He rechecked all body parts. He wanted to be sure he didn’t leave any on the floor.

* * *

The Nine moved into additional training disciplines where they were taught how to wear pressure suits, and where they were introduced to weightlessness, vibration, and noise—even simulated lunar gravity.

John and Neil tough it out in their self-raised “Choco Hilton” in the Choco Indians’ tropical rain forest in Panama. (NASA)