Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 (4 page)

Read Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 Online

Authors: William Boyd

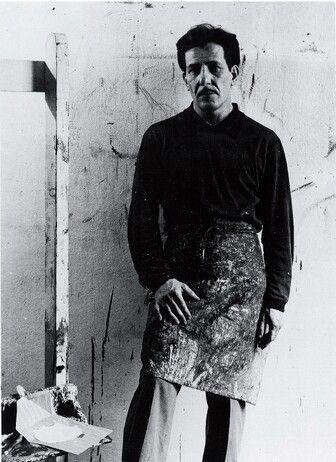

Frank O’Hara with Franz Kline at the Cedar Tavern, March 1959

Janet Felzer abandoned the Aperto Gallery in Hudson Street and moved uptown to Madison Avenue (and 78th Street) where she opened the Janet Felzer Gallery in 1954 with another landmark show including works by Philip Guston, William Baziotes and Martha Heuber (Todd’s sister). Nat Tate moved north with Janet Felzer, and in the 1954 exhibition he had one large solitary canvas called

White Building

. This announced the start of another sequence, this time in oil, a series of façades of a house with crudely painted doors and windows in black almost invisible under a screen of thinned white oil paint. ‘Like ghost houses,’ Mountstuart remarked. The deliberate monochrome was again individual, owing nothing to Kline, Motherwell or de Kooning – with the first of whom Nat had now become friendly. They were in fact, as Mountstuart recognised, images of Windrose, painted from photographs, of a large size (5´×8´) and, according to Janet Felzer, Nat completed ‘at least eight or ten’ over the next few years. Barkasian bought them all, hanging them in sequence in the capacious entrance hall at the house, where they were, reputedly, most impressive. None has survived.

Franz Kline, 1956

Mountstuart was a particular admirer of the

White Building

sequence, intrigued by the way the much erased and repainted and then overpainted simplifications of window embrasure, arch, column, frieze and portico somehow defied obliteration by the layers of white, turps-thinned oil paint that was repeatedly laid over them. What looked like a scumbled and overworked gesso field with blurry grey/black markings revealed itself, after some moments of staring, ‘to be a real record of a real house in a real place’. Mountstuart thought also that these spectral canvases ‘were a profound statement of time and time passing, of the brave refusal of man’s artefacts to be completely overwhelmed by oblivion’.

The mid ’50s marks the period of Mountstuart’s closest contacts with Nat Tate. He weekended at Windrose several times and came to know the Barkasians. The photo of an uncomfortable looking Peter Barkasian on the beach at Fire Island was taken by Logan Mountstuart in 1957. A measure of this new relaxation was the sale to Mountstuart of three drawings from the

Bridge

sequence. Barkasian realised that he could not, with Nat’s mounting renown, maintain a monopoly on the artist’s work. Consequently, Janet Felzer was allowed to sell a few drawings and some gouache studies for the

White Building

oils. As Nat Tate’s profile was steadily raised there were many more offers made than there were works available. Nat was not a fast or prolific artist, indeed it was sufficient for him merely to show from time to time; unlike most of his contemporaries he had no economic incentive: Barkasian’s generous allowance was maintained and he paid Janet Felzer the market rates for Nat’s work and, as Felzer explained to Mountstuart, she could hardly complain. In terms of the commission she made, Nat Tate was virtually her most successful artist. Even so, she continued to encourage and push him, persisting with the idea of a solo show, but Nat was reluctant, happy merely to hang with other artists in her gallery.

This was, perhaps, the period of his life when he was at his most content, accepted and admired by his peers, finally free of Windrose, living on his own in Manhattan, with a lively group of artists and friends, most of whom were savouring the fruits of their success and international acclaim. Nat Tate cut a slightly different figure from his peers – a tall, fit-looking young man, he was well groomed, disdaining the jeans and dungarees favoured by other artists of the New York School. In the summer he was always deeply tanned, Mountstuart remembered, also commenting that he seemed to choose his clothes with care – such as midnight-blue suits with cream linen shirts – and that he had a predilection for light, self-coloured ties, ivory, silver-grey, pale banana yellow. He was handsome – and he knew it – but there was nothing predatory or narcissistic about him. ‘Sometimes he seemed almost embarrassed by the stares he attracted from both males and females,’ Janet Felzer noted, ‘as if to say “Why are they looking at me? What have I done now?” ’

Peter Barkasian on the beach at Fire Island, 1957. © The Estate of Logan Mountstuart, 1958

By the mid-1950s, the era of Abstract Expressionism and Action Painting was well under way. Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning led the pack, closely followed by other artists such as David Smith, Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell. The New York School was into its well-heeled, drink-fuelled, fame-driven stride. Like many artistic move

ments that claim the attention of the media, a deal of self-

conscious myth-making occurred and stereotypes duly emerged (the artist as visionary drunk, the artist as surly macho brute, the artist as brawling suffering genius), as well as many a brief minor talent, seeking their moment of glory. Much of the initial socialising – the drinking, the talking, the sex – centred around the Cedar Tavern on University Place and 8th Street in Greenwich Village.

Regulars at the Cedar Tavern, 24 University Place, October 1959

Frank O’Hara at the Museum of Modern Art with (left) Roy Lichtenstein and (right) Henry Geldzahler

As Elaine de Kooning said, ‘around 1950 everyone just got drunk and the whole art world went on a long, long bender.’ The Cedar Tavern, a drab, shabby place (which is still there, still remarkably authentic), is in a way the symbolic artefact of the period – playing the kind of role the Café Flore does in the annals of left-bank Parisian Existentialism – eternally conjuring up an image of famous artists drinking at the bar, talking and quarrelling about art, turkeycocking, eyeing up the art groupies that were drawn to the place, curiously circling them. It was a charged, exciting time, and for Nat Tate a first real taste of escape, of true independence. Like everybody else, like every other artist he met, Nat began drinking heavily, joining the long, long bender that was going on around him. Gore Vidal met him at this time and remembered him as an ‘essentially dignified drunk with nothing to say. Unlike most American painters, he was unverbal. “He was a great lover,” Peggy Guggenheim told me years later. “Almost in a class with Sam Beckett who had bad skin. I loved Sam for six months. A record for me. Nat for – oh, six weeks at the outside.” ’

4

For Nat Tate, Frank O’Hara remained a mentor-figure and friend. It is not clear if they were ever lovers (O’Hara was living with Joe LeSueur from 1955) but the relationship took on more professional dimensions when O’Hara, as curator, selected two of the

White Building

paintings for the 4th São Paulo Bienal in 1957. There is an uncollected poem O’Hara wrote around that time called

What if we hadn’t had such great names?

that captures some of the flavour of those heady days in the ’50s, when the art world looked to New York for its inspiration, and the city’s artists, it seemed, could do no wrong.

What if we hadn’t had such great names?

What if we had been called

Gilbert Kline, Jonathan Pollock, Cyril