Nakoa's Woman (10 page)

Authors: Gayle Rogers

“Anatsa, I will not listen to you talk such nonsense. How can that bird singing have anything to do with you? Maybe you hear the wind at night moving the bells of the tipis, and the sound of them makes you dream something. But what is a dream?”

Anatsa looked at Maria strangely. “They are my dreams,” she said. “The Indian has always listened to the speaking of his dreams. Every brave seeks his medicine in a dream. If the bravest warrior dreams a bad dream before battle, he will not fight. The voice within him is a sacred voice, and is the voice of the Sun.”

Maria looked away. “I will not argue with you if this is part of your religion—your talk with the Great Spirit.”

“We all walk our own path,” Anatsa said, “and every path leads to the sun.”

Maria sighed. “I do not follow your words.”

“About Nakoa,” Anatsa said, “I cannot ask, if it is not in your heart to tell me.”

“He did not hurt me last night,” Maria said. “He slapped my face in great rage, but his touch was not strong, and when we had finished talking, our talk with each other was not angry.” Hotness came to Maria’s face, and she clasped her hands tightly. “He is not taking me—the way he was. He is going to make me his second wife.”

“Maria! Maria!” Anatsa exclaimed softly. “You can have a good life with us now! Maria, you will not be unclean, and as Nakoa’s wife…”

“Second wife,” Maria said, her voice bitter.

Anatsa heard the bitterness, and some of the gladness left her face. “You will be under the protection of Nakoa,” she said. “You will be kept clean. You can have a voice to speak to the Great Spirit! Nakoa will always be rich, Maria. Any girl in this village would give deep thanks to be Nakoa’s second wife!”

“I do not want to be farmed out.”

“I do not know your last words.”

“I do not want to be used by every man in your village, but I do not want marriage with Nakoa either. I do not want to be—”

“To be what?”

Two other women had come to the lake, and Anatsa whispered so that they wouldn’t hear.

“I do not want to be a second wife,” Maria said.

“You will have to accept this,” Anatsa said. “Accept this and be thankful in your heart that you are being taken in marriage. When it is announced that Nakoa will marry you after he marries Nitanna, Siksikai will not harm you. He is afraid of Nakoa, for he knows Nakoa would enjoy ending his life.”

Maria looked affectionately at Anatsa. “Why do you think of death and killing and shadowed dreams when your thoughts should be on marriage and children?”

“I will not marry,” said Anatsa.

“There were six notes even to that bird’s song. If you are the song of a bird, you have to take six steps, too!”

Anatsa smiled.

“You were born …”

“And I was crippled.”

“And you were crippled, and you fell in love.”

Color came to Anatsa’s thin face.

“There are three steps already!”

“And I have grown in friendship with a white woman.”

“Then you must take the fifth step, little bird! You must marry!” “Maria, Apikunni does not know me.”

“He looked you full in the face at the Kissing Dance. Is this usually done?”

“No.”

“Then you will take the fifth step and marry Apikunni.”

Anatsa laughed, the first time that Maria had ever seen her laugh. Her eyes shone. “Tell me how! You worked your magic on Nakoa. Give me some of the magic that you brought from the land of the rising sun!”

“I will! I will tell that you have a lover in the Mutsik, and you must tell no one that this is not true. I will tell the whole village this.”

Anatsa laughed again. “And how can you tell the whole village this?”

“By telling Atsitsi of course!”

Anatsa smiled, then shook her head. “I do not want it thought that I would go to a man’s couch without marriage!”

“Of course you do not. I am sorry for what I said.”

“I walk in the shadow of those who are whole, but I am not only my body. If I could, I would not give the body that I have to a man—to a man that… No, I speak with straight tongue—not even to Apikunni!”

Maria understood her faltering words. “I know that you wouldn’t,” she said. She looked at Anatsa and heard a soft Spanish lullaby, and then saw her mother’s face cold and waxen in her coffin and the white naked breasts of Meg Summers. She shuddered.

“Why do you tremble, Maria?” Anatsa asked.

Maria looked out at the lake. “It is those women in the water. They must be cold.” The two women were swimming. The Blackfoot were strong swimmers, and the women used a stroke that Maria had never seen before. They did not use the breaststroke of the white man, but drew one arm at a time entirely out of the water and reached forward and pushed back with it. They seemed to move faster with much less fatigue.

“That is not why you shuddered,” said Anatsa.

“Your words made me think of my mother. You are a lady, Anatsa. A true lady. I have only known two of them. My mother, and Ana, my baby sister.” And they are both dead. They are both dead, but the breasts of Meg Summers are alive and warm.

They walked slowly back to the village. Anatsa left her, and went toward the inner lodges, and Maria saw her nephew Mikapi run to meet her. Anatsa ruffled his hair affectionately, and then placed her hand upon his shoulders, as the two of them talked excitedly. Maria watched them until they were out of her sight, and then turned toward Atsitsi’s.

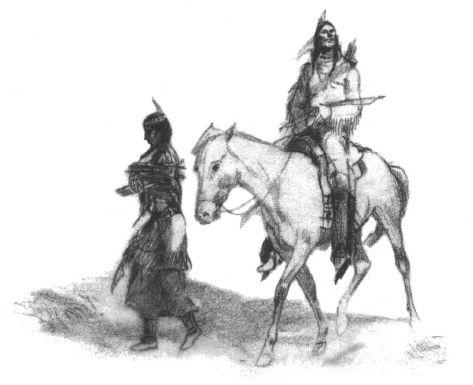

Apikunni and Anatsa

The spring of 1846 had been unusually warm and mild. Summer came early to the prairie; it touched the columbine, gaillardia, and the mountain golden rod, and they all bloomed before their time. Because the warmth of summer had come early, the running time of the buffalo, usually in the moon when the leaves turn, came in the moon of the flowers. Less than thirty miles from the village their shaggy forms blackened the prairie for miles around, and so it had to be the time for their hunting.

All the societies of the Ikunuhkahtsi, except the Knatsomita and some of the Mutsik, left with their women for the buffalo grounds. The warriors that remained behind were to guard the village. For in this year, known on the Indian time stick as the sun of early spring, there had been seen sure sign of an enemy.

The Blackfoot nation with its three tribes of Pikuni, Kainah, and Siksikauwa, and their two allies, the Sarcee and Atskina, protected their lands with studied vigilance—but their land was vast. Their holdings stretched from the northern branch of the Saskatchewan River in Canada, south to the mouth of the Yellowstone, and from the western summits of the Rockies east into the land of the Crow and the Dahcotah. Beyond this land was the Blackfoot enemy, the Crees to the north, the Assinoboines to the east, the Snakes, Kabspels, and Kutenais to the southwest and west. But most dreaded and hated of all was the Crow from the Badlands. For the Crow alone came boldly into Blackfoot land in the eternal Indian search for coups. To the Crow, a woman’s scalp, taken within sight of her village, counted as a coup equal to an Indian male’s, or the stealing of a great warrior’s horse.

In that moon of the flowers, in July 1846, at the time of the great buffalo hunt, came the first sign of the Crow. There was a stray dog found near the village with a pack of Crow moccasins tied to his back, bruised grass made by a camp was seen in a mountain meadow, strange moccasin markings were discovered in the mud of a mountain stream bed, and so it was clearly known that a Crow war party was waiting in the mountains for the taking of scalps. The Mutsik who remained in the village rode out on patrol of the camp’s surrounding territory, and when they rode back, they were met by the Knatsomita, who did not return to the village until daybreak. Separate war parties rode to the mountains. Braves, mounted on warhorses, wearing war shirts of two thicknesses and carrying skinning knives for the lifting of scalps, became a common sight to Maria. She saw at close range the ash war bow and the war quivers filled with barbed arrows, glued so lightly to the shaft that the point of the arrow would remain in the wounded man even after the shaft was removed. Each warrior’s quiver contained one hundred arrows; he could fire from fifteen to twenty in one minute.

During the new vigilance the women were told to use the lake and to walk to the river only in the light of full day. They were to travel in groups, and to follow only the paths guarded by mounted Mutsik. Anatsa and Maria went to the lake together, but when Anatsa’s sister Apeecheken became ill in her pregnancy, it fell completely upon Anatsa to bring wood back from the river. At first Mikapi accompanied her, but with the inconsistency of a child, he became bored, and let Anatsa go with the women while he rode with some of the men, or gamboled with the other young boys of the tribe. Even with the other women, Anatsa hated going to the river, because across from it were the Pikuni burial grounds, with their dead buried openly on platforms high in the trees. She had been to the grounds only once, and she would never go again. There the sky had a different color to her, the wind a different sound, and the sky and the wind were both hungry to imprison her there forever. She could not remember when she had started fearing the dead sleeping across the water. She must have been born afraid of their shadow.

On the second day after the hunters had gone to seek the buffalo, Anatsa walked to the river, lagging behind the other women. Maria was not with her, and walking in the hot sunlight, she began to feel terribly alone and lost from the village behind her and the women ahead of her. If the Mutsik were patrolling the path she did not meet them. Anxiously she struggled to catch up with the women.

The banks of the river were cool, and deeply shaded. Anatsa gathered the scrub wood from among the willow thickets and snowberry bushes, listening to the murmuring voices of the women working to her right. The river rushed loudly through the groves of aspen and cottonwood that bordered it, and its noise made her unaware that the other women had gone.

She straightened, and listened intently for their voices. There was no sound of them above the water. Hastily, without even enough wood, Anatsa turned to go back to the village. She passed a bush of serviceberries, now ripe and ready for picking. She could have gathered some; Apeecheken could eat berries if she couldn’t eat meat, but Anatsa was too afraid to stop. All of her body listened for a strange or an alien movement, and her heart began to beat frantically with the feeling that she was not in the thicket alone. Would the scalp of a crippled woman count as a coup? Why would it not? she thought. Her scalp would bear no mark of a crippled leg!

Through the shadows of the trees she walked quietly, trying to move without any sound at all. In the willows ahead of her she saw a slight motion, but it was so slight that it could have been just a movement of the wind or the quick touch of some light-footed animal. Anatsa stopped and hugged the wood that she had gathered to her breast. Someone stood behind the willows; she knew this. Her heart struck at her in terror. Minutes passed, and she still remained motionless. The wind moved suddenly through the aspens, making them glitter with the sunlight they hid from her, and then the cottonwoods moved too, more slowly and lazily. The river rushed monotonously on, washing the shore of the dead, its water keeping the restless spirits of the ghost hills from the Blackfoot camp. Oh, if she were dead, she would travel the great Wolf Trail and never come back to stir unrest among the living! She would never speak through the air and the wind that another would come soon to rest beside her.

Something ahead moved again, and Anatsa saw a tall man in buckskin. She screamed and dropping her wood, tried to run from the thicket. “Anatsa!” someone shouted, and she stopped running, panting wildly. Apikunni walked to her. “Why are you here alone?” he asked her angrily. “Why have you come for wood at all?”

Shaking violently, Anatsa looked down. “There is no one else,” she said finally. “Apeecheken is sick with her baby.”

“You could come with the other women,” he said sternly.

“I cannot keep up with them.”

“I could have been Crow,” he said, still angry. “This morning their prints were found across the river, in the burial grounds.”

With her head averted from him, Anatsa walked slowly back to her wood. He followed her, watching her limp, seeing her drag her almost useless leg. She knew that he watched her leg, and her face became hot with misery.

“The Crow do not enter a burial ground at night either,” he said. “They have been there when women were here, gathering wood.”

“I am sorry,” Anatsa whispered.

“You can’t even run!”

She looked up into his face for the first time. “Or walk,” she said quietly. Their eyes held for a moment.

“Tomorrow I will come with you, and I will see that you return safely to the village. Do not ever come here alone again!”

“All right,” Anatsa said softly. She started through the thicket, and on the prairie, she saw Apikunni’s horse. He followed her and mounted his horse, riding slowly beside her. For a while they didn’t speak, Anatsa becoming more and more aware of her dragging walk. “I do not want you to wait for me!” she said suddenly.

“I will ride with you every day like this,” he said shortly.

The wood began to scratch Anatsa’s arms. When she had learned that Apikunni had not gone to the hunt with Nakoa and most of the Mutsik she had felt joy, but now that he was so close beside her, and spoke to her, she fervently wished that the earth would open up and swallow her. The wood was miserable. If she stopped and shifted it so that she would be more comfortable, she would be with him longer, and she couldn’t bear it. Her growing misery was broken by the sight of Maria walking toward them, followed at a distance by the sweating Atsitsi.

“You get by-damn wood!” Atsitsi was shouting.

“If I get the wood, I’ll have my own fire!” Maria shouted back.

“Full of big Maria now because Nakoa take you after Nitanna! He never marry you, no matter what he say! He never marry you—big fool Maria!”

“Oh, shut up!” Maria shouted. She saw Anatsa and Apikunni and smiled. “Tonight Atsitsi and I are going to have two fires,” she said.

“Hers and mine! Now that I am going to be wife to Nakoa, she can get her own wood!”

Atsitsi had caught up with her. “White woman full of Maria now,” she said.

Apikunni and Anatsa looked puzzled, for they could not follow Atsitsi when she broke into English.

Atsitsi scowled at Apikunni and scratched herself. “Why do you ride with Anatsa?” she asked him.

“Crow have been at the burial grounds. Do not go to the river by yourselves. After I take Anatsa to the village, I will come back and ride to the river with you.”

Maria laughed. “No Crow, no matter how ragged and starved for coups, would get near me with angel Atsitsi protecting me. That is all she has to do just smell for them!”

“I protect you for hell!” Atsitsi raged, and sat down. “We wait,” she said in Pikuni, and Maria sat down too, but a good distance away.

Apikunni smiled at Anatsa as they left Maria and Atsitsi alone. “They have their own language,” he said. “Nakoa’s woman is very beautiful,” he added.

Anatsa felt like nothing beside the incomparable beauty of Maria. The wood had scratched her arm, and shifting its position, she scratched herself again. Her arm was bleeding.

“You have hurt yourself,” Apikunni said. He reached down suddenly and took the wood. She was so thin; he had never before known that she was so delicate. He had heard that she prepared skins for lodges and clothing faster than any woman in the village, yet how could she even flesh a hide and soften it when she was so frail? She looked terribly unhappy. “What is the matter, Anatsa?” he asked her gently.

“You should not carry my wood.”

“That is not why you look at the ground and act afraid to meet my eyes.”

She said nothing, and he saw the hot flushing of her cheeks.

“You are friends with the white woman,” he said, trying to put her at ease with him.

“Yes,” she said briefly, still averting her face.

“She is beautiful, but she will bring no happiness to Nakoa.”

“Why do you say this?” Anatsa asked.

“She is white.”

“What reason is that?”

“She will always want her own people. She will not accept the people of Nakoa, and if she cannot accept them, she cannot accept him.”

“Why couldn’t a white woman accept us?”

“We do not walk in the white man’s way or wear his dress, and because we do not he thinks of us as animals, no better than the buffalo that he destroys without reason on our prairie.”

“How do you know this?”

“Natosin has talked to me of the white men. He used to travel to the Mandan villages and visit with his friend Mantatohpa before the sickness brought to them from the white man killed them all. The white man came to the Mandans in trade, and because the Mandans accepted them, sickness from the white man’s boats killed every man, woman, and child in their village. Natosin was there when they died. That is when all of his wives and children except Nakoa died with the sickness too.”

“Did Natosin see the white man too?”

“Natosin met only one white man, a medicine man who came among the Mandans to draw the Indian. He lived among the Mandans and the Dahcotah and persuaded some Indians to go back with him to the white man’s land, and there the white man looked upon the Indian with mockery and set him apart from men. The white medicine man had accepted the Indian with open heart, but the whites don’t listen to the voice of their medicine men.”

“Maria does not look upon us as something apart from men.”

“Maria is held as Nakoa’s captive. She cannot be free in her thinking.”

“Maria does not think with the mind of others! This is done by people with fear in their hearts, and Maria knows no fear!” For the first time Anatsa completely forgot herself and was fully communicating with Apikunni. Her beautiful eyes were flashing in anger and Apikunni looked at her strangely. He had never seen her before.

“Why do you become angry?” he asked softly.

“The white woman knows no fear,” Anatsa repeated stubbornly.

“Or wisdom. What did she think Nakoa’s feelings would be when she scratched his face and went to the Kissing Dance and chose Siksikai as her lover?”

“Who has thought of her feelings? She is white, but she has the feelings of an Indian! He should not even force her to marry him!” Apikunni looked at Anatsa in astonishment. “She is his!” he said. “She is his!” Anatsa mimicked furiously. “She is his!”

“He saved her life. He wants her and she is a white woman!”

“Oh, oh! So she should be destroyed—like the white man kills the buffalo?” Anatsa was shaking in rage. Apikunni watched her wordlessly. Her face was flushed and she met his eyes fearlessly. Why had he thought her pale, a shadow of a woman? He began to smile down at her thin outraged face. “What should Nakoa do with this woman?” he asked.