Nagasaki (6 page)

Authors: Emily Boyce Éric Faye

There is no ideal way to begin a letter to a stranger. It’s true we are not total strangers, though we have only seen one another once ‘in real life’, and in the strangest of circumstances. I’ll waste no more time on the preliminaries, Shimura-san. Above all, I wanted to express my gratitude for your restraint at the trial. That’s the only word I can find for it, restraint.

She put her pen down at the end of this sentence, laying it across the paper at an angle like a fallen tree trunk blocking her train of thought. What could have felled it? A storm raging inside her skull? The woman hovered over the page, hoping to pick up where she had left off (just as staying in

the same position in bed can apparently help you go back to a dream begun earlier in the night). She wanted to seal the envelope by the end of the day and pass it on to the estate agent (having added the words ‘FAO Mr Shimura Kobo, the homeowner’). It would be a relief. Having waited so long for this moment, she would at last be able to explain herself. She would be able to tell herself she had recovered from her earlier shock at the ‘For Sale’ sign. The pad of writing paper bought before sitting down at this table struck her as dauntingly blank. How many pages must she fill? She wished there was a short cut so she could transmit her thoughts directly from her mind to his. In truth she wasn’t terribly fond of writing and had hardly ever done it. And yet she must.

Restraint, or moderation if you’d rather. Either way, it meant a great deal to me, both during the trial and afterwards, when I found myself alone with my thoughts.

Please understand, this letter asks nothing of you. You have well and truly seen the back of me; I unintentionally hurt you and will not do so again. Only, when

I saw the ‘For Sale’ sign at your door, my elation at having regained my freedom turned to sadness, and I selfishly said to myself: we’re on the same footing now, he and I, both banished from the same kingdom. Please forgive me for having had such a shameful thought, which I quickly dismissed but wanted to share with you all the same. I would also like to ask your forgiveness for all the trouble I’ve caused you; what you said at the trial has stuck in my mind: I can’t live there any more.

No doubt you will be wondering why I am poking my nose in, having been the cause of all this, and how exactly I can claim to have an attachment to something that was not mine but belonged to you. This will surprise you, but the truth is that, despite appearances, my attachment to that house was actually deeper than yours, and the reason I am writing is to explain how my moving into your house had nothing to do with chance, contrary to the impression given by the investigation.

As you heard during the trial, I found myself out of work two years ago. At my age, I had no prospect of finding another

job. Retirement was still a long way off, but I no longer had a place in the world of work. I was condemned to be neither one thing nor the other. Cursed are the single and childless! Once I was no longer entitled to unemployment benefit, I had to give up my lease. The first stirrings of shame drove me out of my neighbourhood.

After selling the handful of electronic devices and decorative trinkets that I had about me, I realised that everything that mattered to me could easily fit inside a small rucksack and a shopping trolley. I found myself on the streets in high summer, last year. The rainy season had come to an end a good week earlier. It was the ideal time to learn to sleep outdoors, and learn I did. At night, I settled down a few metres beyond the last houses on the hill, which often lay empty and were insalubrious – but I imagine you know the top part of town as well as I do – surrounded by cemeteries and temples harking back to bygone days, and I was not to be pitied. At that time of year, everything still seems easy. But I won’t go into the whole story of those strange few weeks which count, if not among the

happiest, then at least among the freest of my life. I went out walking in the cooler hours in search of food; when it was too humid, I simply floated above the city in the perfect shade of the bamboos.

What did I have left? At night, lying down, the same thought kept coming back to me: this whole thing is a prank. One big joke. Sooner or later, I’ll get an explanation. I’ll be offered excuses and I will know the truth. We will all achieve enlightenment. It’s destined to happen, only we don’t know when. You just have to be patient. And when the time comes, we’ll escape this absurd drama. The trail of breadcrumbs leads towards the emergency exit.

But the time didn’t come. Every night, I lay down full of confidence. It was all a bit of fun and everything would be back to normal in the morning … It simply wasn’t possible that everything could be so utterly senseless, the stars, the wind, humankind.

If there’s one thing I became sure of in the course of those weeks, it was this: there is no meaning. That is to say, it didn’t exist before we did. The idea of meaning was invented by humans as a balm to their

anxieties, and their quest to find it is obsessive, all-consuming. But there is no Great Architect looking down on us from on high. Sometimes, when this realisation made my head spin, I needed a lifeline; I would spread my things out in front of me, keepsakes I had not been able to part with. It was not that I expected them to save me. Yet a pale, cold light radiated from them, like a foundation for the universe; this light had something of the brightness of the stars, for the faces which appeared in my photos were most often those of people who had passed away; the factories where my few cherished possessions had been manufactured must have long ago closed their doors; as for the old key that had never left my side, it had been without a door to open since time immemorial.

Autumn was approaching. The early hours were cooler. Twice I had been caught in the rain as I slept and had been driven from my bamboo. Drenched, I had taken refuge in an abandoned shack a little way down the hill, and waited for the sky to plug its leaks. I couldn’t make the quiet life I had been leading last much longer, and

the knowledge worried me, even panicked me at times. It didn’t cross my mind for one moment that I might move into one of those hovels permanently; they disgusted me. From then on, I began to wander about in search of shelter. Anyone with time to watch the goings-on of a street soon works out who lives alone and what their habits are. For example, some elderly people leave their doors unlocked when they go out shopping. I ‘inspected’ several somewhat isolated houses down overgrown cul-de-sacs. To begin with, I only sheltered in them on nights when it rained heavily. A storm trapped me inside the home of a deaf woman for forty-eight hours. During the day, when the downpours were more spaced out, I continued my walks; in the course of my wandering, I sometimes ended up in the neighbourhood where I had spent my happiest years: between the ages of eight and sixteen. Oh what precious years they were! I kept a lookout for several mornings in a row. Some distance away, I saw a man leaving at around eight o’clock every morning from the house in which I had grown up. In all likelihood he was on

his way to work somewhere. Maybe … I was seized with the desire to see it again. The entrance to your house was really only overlooked by the property opposite. One morning, I was lucky and the old lady who lived there decided to leave the house. She walked slowly down the road, which was otherwise empty. Maybe … I thought I’d give it a go, walked a few paces and rang the bell. There was no one in. You lived well and truly alone. In spite of all the years that had passed, the locks had not been changed. And in any case, you had neglected to lock up that day. There was no need to put my key to use. Before I knew it, I was stepping inside the old kingdom. That is how I found myself in your home one early autumn day, Shimura-san.

It is said that certain breeds of sea turtle come back to die on the beaches where they were born. It is said that salmon leave the sea and come upstream to spawn in the rivers where they grew up. Life is governed by such protocols. Having completed a sizeable cycle of my existence, I was returning to one of my oldest habitats. Site of my eight-year-long ‘age of discovery’. An

age of wonder and untold promise. I dare say in recent times you rarely stopped to appreciate the view from the window of what had been my bedroom – and became yours, many years later. You had perhaps become blasé about it. But imagine what it meant for a little girl like me to take in the sight of Mount Inasa and the bay, the dockyards and all the boats, all at once. Leaning a little to the left, I could see Oura church where I had been baptised, or all the way over to the right, the distant northern neighbourhoods; strange, these Catholic areas razed to the ground by a Christian country’s bomb … There are so few Christians in Japan, it’s as if the raging atoms dumped by America had meant to play a tasteless trick on them.

I loved my bedroom, my balcony on the world, a world reborn after the deaths of many of my ancestors, one 9 August long ago. Eight of my years went by there. How I loved those rooms, those walls … It seems to me it should be written into the constitution of every country that every person should have the inalienable right to return to the significant places of their

past, at a time of their choosing. They should be handed a bunch of keys giving them access to all the flats, houses and gardens in which their childhood was played out, and allowed to spend whole hours in these winter palaces of the memory. Never must the new owners be allowed to stand in the way of these pilgrims of time. I believe this strongly, and should I become politically engaged again, I think it would be the sole focus of my manifesto, my one and only campaign pledge.

One Sunday in autumn, the year I turned sixteen, my parents drove to near Shimabara to visit some cousins. They never came back. A landslide caused by the storm we were having swept the road away beneath them, somewhere up in the mountains. And that was that. I was an orphan. My remaining family members took me in. I went to live with an uncle and aunt. I remember the day I moved out. I never dreamed I would one day come crawling back like a petty thief to hole up in the room my parents had once slept in.

Later, I managed to get into university, in Fukuoka. My studies did not go well. I

couldn’t stick at anything. Little by little, I came to see that the landslide was still going on inside me. It had taken its first prey one day in the typhoon; now it was my turn. The ground continued to crumble, only more slowly and insidiously this time. Piece by piece, it took apart the life I would have liked to lead. Whatever I did, everything fell from my grasp. Some part of the mechanism must have broken. I began to hate the way the world was going and got in with a certain crowd. In 1970, at the age of twenty, I joined the highly subversive United Red Army. The renewal of the security treaty between our country and the United States continued to ally us with the people who had dropped an atomic bomb on my family. The hatred I felt! I spent years hating. Everything else was beside the point. I devoted myself to my red dreams the way others devote themselves to oil painting. But I couldn’t even take my taste for the extreme seriously. We had a passion for failure while hurling victory slogans. One day, some of the group were arrested. I had to lie low. I ended up getting into drugs and my former self dissolved,

the self I had been trying to escape by becoming part of a collective movement. I was given a new identity, brand-new papers. I had a succession of salaried jobs and was never able to seize the second chance that my new name offered me. That’s all there is.

February 2009–April 2010

Éric Faye

Born in Limoges, Éric Faye is a journalist and the prize-winning author of more than twenty books.

Emily Boyce

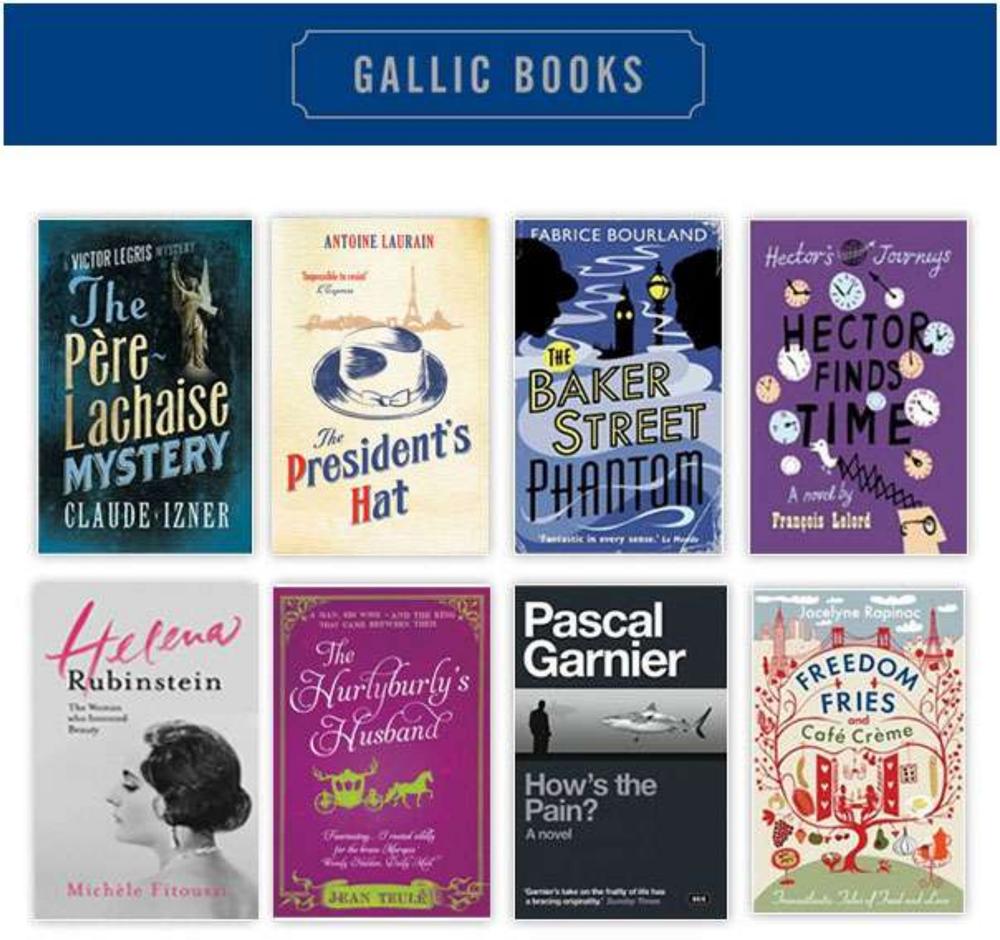

Emily Boyce is in-house translator at Gallic Books. She lives in London.

First published in France as

Nagasaki

by Éditions Stock

Copyright © Éditions Stock, 2012

First published in Great Britain in 2014

by Gallic Books, 59 Ebury Street,

London, SW1W 0NZ

This ebook edition first published in 2014

All rights reserved

© Gallic Books, 2014

The right of Éric Faye to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781908313751 epub