Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation (19 page)

Read Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation Online

Authors: Trevor Wilson

46

UN Working Group,

Human Development in Myanmar: An Internal Report

(Yangon: UNDP, 1998), pp. 11–13.

47

For an overview of the human legacy of conflict, see for example, M. Smith,

Burma/Myanmar: the Time for Change

(London: Minority Rights Group, 2002), pp. 21–28.

48

International Crisis Group,

Myanmar: Aid to the Border Areas,

p. 3.

49

Ibid.

50

The source for this figure is the Ministry of Health, as quoted in:

Review of the Humanitarian Situation in Myanmar,

UN Country Team, pp. 32–33.

51

UN Office on Drugs and Crime, ‘2004 Myanmar Opium Survey — Results at a Glance’, Press Release, 11 October 2004.

52

For example, from 2001 to 2004, an international NGO, Health Unlimited, completed a whole-course immunization of over 50 per cent of children under two years of age in eleven Wa districts (total population 160,000) with the cooperation of the Wa, Myanmar, and Yunnan health authorities. For the experience of another international NGO in Myanmar, World Concern, see D. Tegenfeldt, “International Non-Governmental Organizations in Burma”, in

Burma: Political Economy under Military Rule,

edited by R.H. Taylor (London: Hurst & Co, 2001), pp. 109–18.

53

UN Office on Drugs and Crime, “UN confirms steady reduction in opium cultivation in Myanmar”, Press Release, 11 October 2004. Weather changes are also a factor, especially during 2003–04.

54

Alan Rabinowitz, “Valley of Death”,

National Geographic,

April 2004, pp. 102–17. For other local conservation efforts between 1999 and 2003, see Lasi Bawk Naw,

Biodiversity, Culture, Indigenous Knowledge, Nature and Wildlife Conservation Programmes in Kachin State, Myanmar

(Myitkyina: YMCA, 2004).

55

International Crisis Group,

Myanmar: Aid to the Border Areas,

p. 13.

56

Interview with Aung Kham Hti, 15 September 2004.

57

See, for example, Kyaw Yin Hlaing, “Burma: Civil Society Skirting Regime Rules”, in

Civil Society and Political Change in Asia: Expanding and Contracting Democratic Space,

edited by M. Alagappa (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), pp. 389–418; and the essays by D. Steinberg, M. Smith, Z. Lidell, and M. Purcell in

Strengthening Civil Society in Burma: Possibilities and Dilemmas for International NGOs,

edited by T. Kramer and P. Vervest for Burma Center Netherlands & Transnational Institute (BCN/TNI).

58

See, for example, Global Witness,

A Conflict of Interests: The Uncertain Future of Burma’s Forests

(London: Global Witness, 2003).

59

Statement by Mr. Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro: Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar

(New York: UNGA, 59th Session, 28 October 2004). p. 4.

60

Burmese Border Consortium,

Burmese Border Consortium Relief Programme: January to June 2004,

pp. 2–7.

61

Global IDP Project,

Myanmar (Burma) Country Report

(Norwegian Refugee Council, 1 July 2004).

62

Interview with Aung Kham Hti, 15 September 2004.

63

See, for example, “From the UN Secretary-General”, UNIC/Press Release/233-2004, 17 August 2004.

64

See, for example, “Myanmar leader assures turned-in armed groups of no policy change”,

Xinhua News Agency,

7 November 2004; G. Peck, “Ethnic Peace May Be in Jeopardy in Myanmar”,

Associated Press,

22 October 2004.

65

Interviews, 26 October, 2 November, 6 November 2004.

66

S. Montlake, “Burma’s disorientated rebels”,

BBC World Service,

8 November 2004.

67

See note 23.

68

See, for example, Kyaw Zwa Moe, “‘Game Over’ if NC Proceedings Not Changed, Says Ethnic Leader”,

Irrawaddy News Alert,

7 May 2004. The decision of UNA parties was also made on the basis of other alliances, including the United Nationalities League for Democracy and the Committee Representing the People’s Parliament.

69

MTA Homein Region Group, Ex-KNU Phayagon Special Region Group, DKBA and Haungthayaw Special Region Group, Burma Communist Party (Rakhine Group), Kayinni National Development Party Dragon Group, Kayinni National Unity and Solidarity Organization, Mon Splinter Nai Saik Chan Group. Another individual paper was submitted by the Pao National Organization, which had been active in the earlier National Convention, 1993–96.

70

The full list is: Shan State Army (North), New Democratic Army-Kachin, Palaung State Liberation Party, Kachin Defence Army, Kachin Independence Organization, Kayan National Guard, Karenni Nationalities People’s Liberation Front, Kayan New Land Party, Karenni National Progressive Party (Splinter, Hoya), Shan State Nationalities People’s Liberation Organization, New Mon State Party, Shan State National Army and Mon Armed Peace Group (Chaungchi Region).

71

The National Convention Working Committee argued that certain expressions or ideas were contrary to the existing “104 detailed basic principles”.

72

Military government officials reportedly do not want individual state constitutions since there could then be fourteen in the country: seven for the ethnic states and seven for the divisions.

73

Because the ethnic states adjoin neighbouring countries, minority leaders want special rights in this sphere.

74

For example, “Ceasefire groups must insist on equal rights say Burmese ethnic leaders”,

Democratic Voice of Burma,

1 November 2004; “Burma’s Ethnic Nationalities Council held meeting”,

Democratic Voice of Burma,

31 October 2004.

75

Ceasefire leaders, however, believe that there are a variety of ways in which the issues of demilitarization can be achieved, ranging from the creation of new political parties to different kinds of military or policing authorities.

76

Interview with David Taw, 6 September 2004.

77

UN Wire, 12 March 2003.

Reproduced from

Myanmar’s Long Road to National Reconciliation,

edited by Trevor Wilson (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006). This version was obtained electronically direct from the publisher on condition that copyright is not infringed. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior permission of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Individual articles are available at http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg

http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg

Sean Turnell

In 2004 Burma’s economy was convulsed in a monetary crisis. Triggered by the collapse of the country’s nascent private banking system the previous year, this latest drama has deeper roots in, and to some extent disguises, the longer-term malaise that has characterized Burma’s economy for four decades.

Burma’s economic stagnation, not readily identifiable from its official statistics, has a myriad of causes, including a policy-making process that is erratic, arbitrary, and usually counter-productive. Over and above policy, however, Burma lacks the fundamental institutions that history tells us are necessary for a functioning market economy. Principal amongst these institutional absentees is a regime of enforceable property rights.

In the following section, the state of Burma’s economy in 2004 will be assessed, beginning with an exploration of some relevant “numbers” — data that highlights the damage wrought by Burma’s latest monetary crisis, and data that casts doubt on the narrative of economic success suggested by the country’s official statistics. Next, the author examines some of the ostensible causes of the latest crisis, highlighting

macroeconomic and other policy failures. It is suggested that these are but symptoms of a more profound malaise which is founded in the failure of Burma’s government to establish a credible regime of private property rights. The absence of these rights presents the principal obstacle to private capital formation in Burma, not least as a consequence of the extent to which “money” itself is compromised.

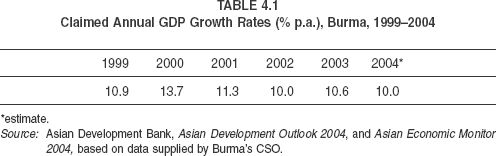

Burma has not published a full set of national accounts since 1999. However the country’s Central Statistical Office (CSO) does supply certain data, including its estimates of economic growth, to multilateral institutions such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Such data paints a rosy picture of Burma’s economy, as

Table 4.1

indicates.

If the CSO’s numbers are indeed an accurate description of Burma’s economy, then the country must assuredly be riding an economic miracle of epic proportions. Growth rates such as those shown in

Table 4.1

are almost unprecedented, with the exception only of the (doubtful) experiences of China today and the Asian “tigers” of selected memory. The figures would seem to be proof of an economy that is not only growing rapidly but, as the growth rates for 2003 and 2004 imply, also one that is extraordinarily resilient to misfortune — including the latest near-collapse of its financial system.

Alas, however, Burma’s official statistics bear little relation to the reality of the country’s economic performance. Subject to almost every conceivable obstruction to statistical best practice — from the low pay, scant resources and corruption of Burma’s civil service, to the existence of a “black” or shadow economy that stalks the recorded one, to the propaganda usefulness of “good news”, and to plain wishful thinking — Burma’s official statistics can only be regarded as suspect and more than usually requiring of a methodology founded on asking the question:

cui bono?

1

Of course, this does not mean that constructing an alternative, more reliable, statistical narrative of Burma’s economic performance is easy or even possible. The lack of reliable information out of the country necessarily precludes precision whosoever should claim it, and this author can only but be in agreement with Dapice, that economic analysis of Burma can only be “a series of more-or-less informed speculations rather than a standard exercise in processing data”.

2