My Share of the Task (52 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

O

n the second day of the listening tour, June 19, we visited eastern Afghanistan. We stopped off first at Bagram Airfield, north of Kabul, where I'd spent so much time between 2002 and 2008. What had been a mine-strewn former Russian base in May 2002 was now a bustling array of aircraft, buildings, and seemingly continuous construction. It served as the headquarters for Regional CommandâEast. Rare in this Coalition war, the RC-East headquarters was not a hybrid staff of many nations. Rather, it had the advantage of being formed around the headquarters of the 82nd Airborne Division, a cohesive team. My longtime comrade and friend Major General Mike Scaparrotti was commanding.

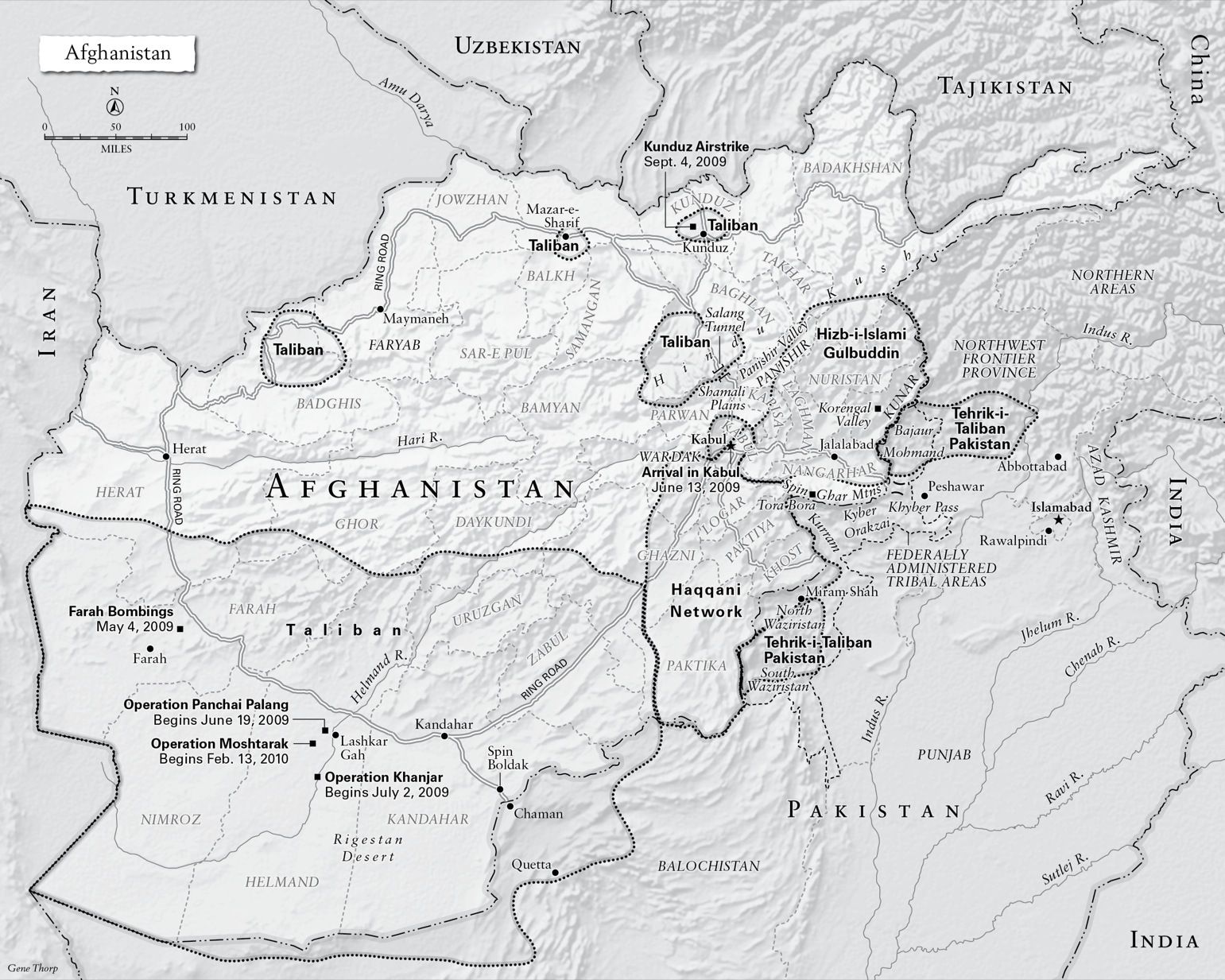

RC-East's area of operations was enormous and difficult. It encompassed the mountainous provinces of Nuristan, Kunar, (where TF 714 had conducted Winter Strike in 2003), Nangarhar and the Khyber Pass, and the Khost “bowl” that looked across the border into Pakistan's northern Waziristan region. Remote outposts sat perched on hilltops while patrols traversed steep, winding valleys.

In addition to its unique terrain, RC-East had the Haqqanis. Formed around their patriarch, former mujahideen commander Jalaluddin Haqqani, yet supervised by sons Siraj and Badruddin, the Haqqani network boasted between four and twelve thousand fighters. They operated out of the Pakistan frontier town of Miram Shah, where T. E. Lawrence had done Royal Air Force service in the late 1920s. Aligned with both the Taliban and Al Qaeda, the Haqqanis waged a semi-independent, vicious campaign against the Afghan government and ISAF to control a large chunk of southeastern Afghanistan.

After staying the night in Bagram, on June 20, we visited Khost and the 4th Brigade Combat Team of the 25th Infantry Division, commanded by Colonel Mike Howard. Mike, now in his forties, retained the wiry frame, red hair, freckles, and penchant for startling frankness that he had when commanding B Company under me in 2nd Ranger Battalion, thirteen years earlier. Mike had commanded two different battalions in combat in Afghanistan. That day, both he and his command sergeant major, Dennis Zavodsky, expressed frustration with the difficulty of delivering development aid to a skeptical population.

“The number one complaint from Afghans is that the Afghan government doesn't deliver on promises,” Mike stressed, as Zavodsky nodded.

It was a predictably sobering message. The countless challenges posed by the Taliban insurgency and Pakistan's apparent complicity had to be addressed. But many of Afghanistan's problems and solutions lay on her own doorstep.

My visit to RC-East confirmed the difficult environment in which they operated, and the threats, like the Haqqani network, they faced. The east's proximity to Kabul and the Haqqani's penchant for jarringly spectacular attacks made the decision to focus arriving forces in southern Afghanistan a difficult one. But in addition to the need to increase security in the Helmand River valley and around the strategic city of Kanadahar, I judged RC-East, and in particular Mike Scaparrotti, to be capable of operating effectively until additional forces were available.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

O

n Sunday, June 21, my ninth day in country, Karl Eikenberry and I chaired a civilian-military coordination meeting, one of the regular engagements designed to maintain the teamwork essential to any counterinsurgency campaign. In a private discussion we also reviewed the forthcoming strategic assessment I'd been asked to conduct. In retrospect, it would have been valuable if the U.S. embassy had also been directed to conduct a parallel analysis. Although we coordinated our review with the embassy staff, the failure to clearly identify and bring to the fore any differing assessments proved to be a problem during the White House's subsequent decision-making process on our ISAF strategy and troop request. We also discussed the civilian-military plan, designed to provide an outline for coordinated execution of operations, that our staffs were jointly developing.

That afternoon, we headed to RC-North, based in Mazar-e-Sharif, and commanded by German Brigadier General Joerg Vollmer. At the time, his area was the most stable part of Afghanistan, but its nine provinces and population of almost seven million was not the quiet domain of the former Northern Alliance that it once had been. Named the United Front by its founders, it was pejoratively labeled the Northern Alliance by its opponents to create a divide between the Pashtuns in the south and the ethnic Tajiks and Uzbeks in the north. In truth, RC-North included a broad ethnic mix, including numerous Pashtun enclaves established in the nineteenth century by Pashtun Afghan kings.

Coalition forces in RC-North were not routinely attacked, but they were stretched thin and unable to adequately secure threatened areas from Taliban infiltration. Such infiltration had by then begun in earnest, particularly in the province of Kunduz. Sitting astride Afghanistan's critical line of communication to the north, which included the vulnerable Salang Tunnel near Kabul, an unsafe Kunduz felt like someone choking the nation's windpipe. I quickly sensed the need to expand and strengthen our ability to secure key areas in the north.

Our trip to the north included a meeting, on June 22, with Balkh Province's governor, the Tajik former high school teacher turned mujahideen commander, Atta Mohammad Nur. This was the first of the contentious meetings I encountered, as Governor Atta, in his “welcome” speech to a room of about forty local leaders and my command team, pointedly complained about Western leaders classifying him as a warlord.

“

We and the people of Balkh Province have removed narcotics from our province but no one praised us, supported us or lent us a hand,” he complained. “Meanwhile, we are stepping up efforts to prevent the trafficking of narcotics throughout Balkh Province every year.”

As Atta continued his speech, my translator whispered in my ear. “He's not happy . . . He's saying Western officials unfairly criticize him, even though he's doing the right things for his province and Afghanistan.” I clenched my teeth to avoid smiling, amused by Atta's posturing to a new commander.

Atta's on-again, off-again support for President Karzai became a constant source of intelligence reporting and I viewed it as one barometer of Northern Alliance thinking. It also highlighted the domestic political maneuvering President Karzai needed to execute in order to build and maintain often fragile coalitions of support.

We'd traveled to and from Atta's provincial center in a ground convoy. Experiencing how an ISAF unit drove in populated areas of Afghanistan disappointed me. Even in a peaceful city like Mazar-e-Sharif, our units drove in an aggressive way they believed was essential to protect against car bomb attacks. But in reality, by forcing Afghan drivers off the road and pointing weapons at an Afghan family, we endangered and insulted the population whose support we needed. It was another practice we needed to fix.

That week, on Tuesday, June 23, I suspended our listening tour for a day for a visit by retired general Jim Jones, President Obama's national security adviser, accompanied by reporter Bob Woodward of the

Washington Post

. In a morning meeting in an ISAF conference room, with Woodward present, I was surprised when the national security adviser said that the administration would not consider further American forces until the full effects of the currently arriving units could be evaluated. Because the last units approved thus far were due to arrive in September, I judged it would be the end of 2009 before we could realistically assess their effect. I was working on what I thought was different guidance from Secretary Gates, to conduct a detailed assessment and an analysis of required resources, which I would submit in the middle of August.

In retrospect, I should not have been surprised. President Obama had voiced strong support for the effort in Afghanistan during his campaign, pledging to add two brigades, which he did. But since the inauguration, despite the partial approval of existing troop requests, and a thorough strategy review of the war culminating in the White House's spring announcement prescribing a better resourced, better coordinated counterinsurgency campaign, the administration had signaled that the U.S. commitment needed careful assessment. They felt we needed to recalibrate the strategy and objectives. I didn't disagree with that. In fact as I deployed to Afghanistan my gut feeling had been that we needed a new approach, not additional forces. But this early in assessing the situation, before I could draw fully informed conclusions, the delayed time line National Security Adviser Jones articulated worried me.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

T

he final leg of our listening tour took us to RC-West, commanded by an Italian paratrooper, Brigadier General Rosario Castellano. RC-West had traditionally been more secure than either the south or east, but had also been the site of the two most significant civilian casualty incidents within the past year. I was concerned about the relatively weak force levels there, the limited interaction they had with Afghan security forces, and the rise of some seemingly intractable resistance in several areas.

In stops across Afghanistan, over countless cups of steaming golden tea, I met with Afghan political leaders, tribal elders, soldiers, and shopkeepers. All were polite, but I sensed a wearied frustration from people whose inflated expectations in the fall of 2001 for political stability and economic progress had been largely unmet. In 2003, “How can we help?” or “What do you need?” still elicited detailed, hopeful answers. By 2009, the questions evoked polite nods but little excitement. They'd been asked too many times with little to show for it. Governance was weak, security was deteriorating, and our apparent ineffectiveness had disappointed once optimistic Afghans.

To be sure, Afghans were the architects and engineers of many of their problems, which they would reluctantly admit. But too often, ISAF and our civilian counterparts seemed disconnected from their lives, unwilling or unable to bridge the gap. To convince the population that we could, and would, win, we needed to engage dramatically more Afghans at every level.

I had hopes for a program first hatched by Scott Miller, Mike Flynn, and me in my office at the Pentagon earlier that spring. Watching from afar, I'd grown frustrated by what I thought was an unserious national approach to the war. As one solution to that, we decided to field a cadre of several hundred American military officers and NCOsâ“Afghan Hands,” after the “China Hands” of the 1930s and 1940sâwho would be trained in the languages, history, and cultures of Afghanistan and Pakistan, and then employed there over a five-year period. On rotations in country and back in the United States, their focus would be the same region or topic. We would send them back to the same districts each time, so that they would maintain relationships with the Afghans with whom they worked. Despite enthusiastic support from Chairman Mullen, the military services' reluctance to contribute personnel slowed the program. It would be early 2010 before the first Afghan Hands arrived and quickly dispersed throughout the country.

The listening tour ended on June 26. That night, the final leg home was in a Chinook helicopter. Earlier that day I'd asked Charlie Flynn to write down his impressions from the last eight days of moving around Afghanistan. As we sat next to each other, leaning close to talk over the rumble of the aircraft engines, Charlie said he'd already recorded his initial impressions. I told him I'd look at them tomorrow, but then told him what was weighing most heavily on my mind.

“It seems like we're fighting five very different wars, not one coherent plan.”

He smiled. Pointing with the small headlamp he wore so he could take notes on night flights, Charlie opened his notebook to show me the first point on the page. It matched my concern exactly: “5 Regional WarsâNot One Fight.”

As we flew on in darkness I thought how it was even more complex than that. While ISAF was fighting five distinct, uncoordinated campaigns we were actually facing something more like twenty-five wars, and scores of insurgencies. The monolithic image of the Taliban personified by the ominous image of one-eyed Mullah Omar was in fact a loosely connected collection of local insurgencies that were energized by local grievances and power struggles. The largely local nature of the insurgency gave it certain advantages, but also revealed its inherent weaknesses and, I thought, fundamental limitations.

During the Taliban's first big coordinated offensives in 2006 and 2007, the Taliban's senior leadership had dispatched trusted commandersâlike the one-legged Dadullahâand delegated the campaign to them. These commanders had managed dispersed but responsive units. But when many of these commanders died or defected, the tethers between the Quetta-based headquarters and the field units grew weaker. Since 2007, the movement had become less hierarchical, less centrally controlled.

As that trend had continued, by the summer of 2009 the Taliban was a heavily local phenomenon. While the senior leadership desired to overthrow the Karzai regime and institute a Pashtun-dominated Sunni theocracy, few Afghans who called themselves Taliban did so explicitly to bring this about. Affinity for the movement's ideology and vision for the country were not the primary motivations, though a sense of Islamic duty was inextricable. Rather, the Quetta-based leadership attempted to swell its ranks by leveraging Afghans' fear of recent experienceâwith bad government, warlords, foreigners, and, to some degree,

modernity itself. In other cases, young men went to fight, and hopefully command, because doing so offered a chance at prestige in the world they knew, a world that offered little else. Others sought a place in the movement to carve out local political power, so that what on the surface appeared like antigovernment insurgent violence was in fact score settling, or clashes over criminal enterprises.