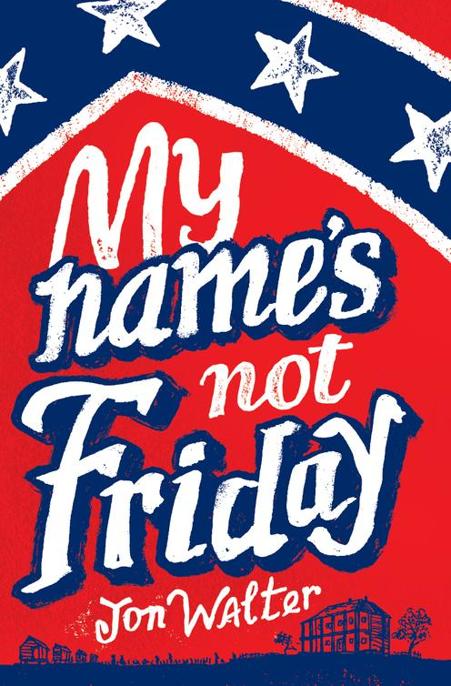

My Name's Not Friday

Read My Name's Not Friday Online

Authors: Jon Walter

To my lovely boys, Jonah and Nathaniel

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Civil War Mississippi

- P

ART

1

Heaven - Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- P

ART

2

Hell - Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- P

ART

3

This Wretched Earth - Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Author’s Note

- Acknowledgements

- Also by Jon Walter

- Copyright

I know that I’m with God.

He’s with me in the darkness. He’s close to me.

Not real close.

But close enough I know He’s there.

Somewhere.

I can feel Him – so I know He must be.

*

It was Him that brought me here.

At least, I think He did. Only it ain’t what I was expecting.

I never thought it’d be dark here – but it is. It’s real dark. Pitch-dark. And it can’t be night-time cos there’s birds singing. There’s a blackbird and a sparrow. There’s all sorts. And them birds don’t sing at night.

’Cept maybe they do in heaven. Maybe they sing here all the time.

*

If I shift my head, it hurts me inside and out. So I don’t try to move. I stay as still as I can.

It’s kinda damp here in the darkness. I got it up inside my nose. A musky smell. Like fur. Like rabbit. Yeah, maybe it’s like a rabbit.

And there’s another smell, a whiff of old shoes, like when you wear ’em for too long after they get wet. But I ain’t wearing shoes. I left ’em in the Sunday box and they ain’t no good to me there. Not any more.

I can feel the dust beneath my toes.

And there’s a bag on my head. The cloth’s against my cheek. That’s the reason I can’t see my feet. I got a bag on my head that’s been used to carry rabbits.

*

I still don’t move a muscle. But in my skin, in my head and my heart, I panic. I feel like a cornered rat, scrambling up against the wall of a deep, dark cellar, breathing fast enough I could’ve run a mile.

So I say to slow down, Samuel.

Slow down now and calm yourself. Take one step at a time. Give yourself the time to think this thing through.

*

I know I’m lying down. I got a sense of me stretched out upon the ground and it feels like I’m lying on twigs and stuff. Yeah, I’m sure I am. I got one sticking in my side and my hands are forced around behind my back and my wrists are sore cos of the rope that’s tying ’em close together. My arms ache too, all up around the shoulders.

I try to move an arm – start to wriggle and twist.

And that’s when I hear the footsteps, coming over to me on the hard ground, making me freeze like a rabbit in a trap, cos all I can think is that God’s coming, that it’s the foot of God upon the ground and He’s coming for me. He’s coming. And He’s wearing big boots.

Well, He lifts me up. My Lord, He lifts me up. He’s got big hands. He’s got strong arms. He flips me on my back and then flips me again, laying me over a mule like I’m some big ol’ bag of potatoes. I know it’s a mule cos it snorts when He lays me down upon its back, like it’s tired of me already. That’s mules for you. Always complaining. Even in heaven.

When He walks away, He don’t go far. I hear Him moseying about in the bushes, shuffling around like He’s collecting things together, putting pots inside of other pots, that sort of thing. There’s the creak of a leather strap being tightened on a saddlebag.

I’m finding it difficult to breathe now I’m slung over a mule with my hands behind my back. My chest begins to hurt and I have to take tiny little breaths that don’t fill me up with enough good air.

Why’s God want to put me on a mule? And why’d He need to tie me up? We made a deal, Him and me, but this ain’t what I expected.

I can’t ask Him. That’s the last thing I can do. It’d show a lack of faith, and I can’t show any weakness. Not now. I won’t show any doubt in my darkest hour. And so I don’t say a thing. I just lie where I am, listening to him walk about in the bushes, the twigs all snapping under His big clomping boots. One time He stops, stands still a while and relieves Himself upon the ground.

I try to wriggle a bit, try to slide down one side of the mule to get myself more comfortable, and I hope God’s not watching me cos I must look like a worm that’s just been unearthed, what with my ass in the air and wriggling for all I’m worth. He sees me though. Comes and stands nearby. And I stop wriggling.

God sucks His teeth. He slaps the saddlebag over the back of the mule, close enough that the thick leather edge pushes up into the top of my arm, and then He leads the mule on and the bones in its back begin to shift as it walks and that makes me even more uncomfortable. In fact, it’s just about the most uncomfortable thing I can remember – that mule’s bones on my bones, the both of us grinding each other up the wrong way and getting on each other’s nerves. If the mules here in heaven are as stubborn as the mules back at home, then this one’ll spit in my eye if he ever gets a chance. My Lord he will. He’ll try and kick me to kingdom come.

We walk like that for a long time. I don’t know where we’re going.

I’d always assumed that when you got to heaven you’d turn up right where you’re supposed to be. I hadn’t figured on having to travel nowhere and I’m wondering how long it’ll be before we stop. But we don’t ever stop. We just keep on walking till I’m hurting so much that I lift myself up to ease the aching in my bones.

And that’s when I fall off the back of the mule.

I hit the ground hard and that mule sees his chance and he kicks out, catching me in the stomach so that all the air rushes out of me.

‘Damn you, mule,’ I curse him. ‘Damn you to kingdom come.’

Straightaway I hear them boots. They walk right up to me

and I sit up quickly, turning my head first one way then the other, trying to get a sense of where God is, cos I’m afraid of Him more than ever on account of having just cussed His mule.

God sucks at his teeth again. I can sense He’s real close, probably crouching right down beside me with His face up close to mine. and He lays His hands upon my head and takes hold of the sack, intending to lift it up, I’m sure, and I quickly shut my eyes because I’m afraid to look upon the face of God, and we’re about to be right up close, my eyes looking into His eyes, and that don’t seem right to me. That don’t seem right at all.

I hold my breath. I squeeze my face so tight it’s as small as I can get it.

Two pink discs appear on the lids of my eyes. I feel the warmth of the sun on my face and I have the breath of the Lord in my nostrils, all smelling of bacon like he’s just had breakfast.

‘Open your eyes,’ He tells me.

He ain’t got the kind of voice you might imagine. He’s all high-pitched and squeaky. A bit like a girl only not a girl.

I shake my head.

I know it doesn’t do to disagree with the Lord, but I’m full of the fear of Him, full of the fear it’s not Him, and I try to look away.

He don’t sound pleased. ‘I said, open your eyes.’

My eyelids are like two heavy doors that I pull up on a chain, all creaking and stubborn. I lift my head to look at Him.

God is smiling at me.

Only not in a loving way.

He has a tooth missing. A half-chewed stick of liquorice

sits in the gap between His teeth, and His mouth has got a wicked smile, kinda lopsided, like He’s gonna laugh in my face at any moment.

Truth be told, He looks more like the Devil himself.

And I’m asking myself, How could this be? How could it have come to this?

But I know it only too well.

And it wasn’t my fault. Not none of it.

When I was first delivered into the hands of God I brought my brother with me. I was just seven years old, and when Mama died giving birth to him, there weren’t anyone left to look out for either of us. Not knowing she was dead, I’d wrapped him in our blanket, folded Mama’s arms against her chest and rested him there, thinking he’d be the first thing she’d see when she opened her eyes.

Once Old Betty arrived like she said she would – bustling in with a bag under her arm and the linen in her other hand – she took one look at Mama, put down her things and crossed herself before the Lord. She said she wished she’d got there sooner, but then forgave herself immediately, confessing that in all probability there was nothing she could have done that might have saved our mama’s life. ‘When God decides it’s time to go,’ she told me, ‘there ain’t nothing to be done about it.’

I learned the truth in that – felt it shake its way right through me till the snot ran from my nose.

‘Come on now.’ Old Betty put a hand upon my head to ease my pain. ‘Least the baby’s good.’ She took him out of Mama’s arms and lifted him high in the air, so his little legs

were waving about like he just couldn’t get away from her fast enough. ‘Did you smack him?’

I shook my head.

‘You shoulda smacked him. Always smack a baby soon as it’s born. Gets it out the way.’ She hit him harder than she needed, just once on his behind, to see if he would cry. He didn’t let her down. ‘You got a fine baby brother, Samuel. You see how strong he is? This one’s a fighter for sure.’

She gave him to me, saying he was mine to look after, but I held him at arm’s length like she’d just given me a lizard or some such thing hatched straight from its egg.

Yes. From the very beginning my brother was both strange and wonderful and I didn’t know what to make of him.

‘What you gonna call him, Samuel?’ Old Betty had put some water on a cloth and she wiped away the smears that had dried on his screwed-up little face. ‘You’re the only one left who’s got the right to name him.’

‘Joshua!’ I said, immediately. ‘His name’ll be Joshua. The same as my daddy.’

I couldn’t remember any more of my daddy than his name – it had been that long since I saw him – but it still felt right to me.

At the time we lived in a little shack of a house on the edge of a town called Haven. It weren’t so big and had only recently got itself a railway. There was a man there who gave me a fair price for everything we owned. That’s what Betty told me. She arranged everything. She took us on the steam train to meet a priest by the name of Father Mosely at another little town called Middle Creek, where he was starting up an orphanage for coloured boys in similar circumstances to our own.

Old Betty took safe keeping of our money, giving what

remained of it to the Father by way of a fee for our upkeep, though I doubted it could ever have been enough, cos in the six years that I lived at that orphanage, Father Mosely never missed an opportunity to tell us boys about the cost of our living there.

We were given food twice a day – once in the morning before lessons and once in the evening after we’d been to the chapel. We had a new set of clothes if we needed ’em, given to us at Christmas, with a spare shirt for Sunday. We had shoes too – a pair of hand-me-downs that we were allowed to wear across the yard when we walked to Mass – though we had to put ’em back in the box by the door once we came back in. I marked the inside of mine both times I got a new pair. That way Joshua could tell which ones to take by the time they came his way, and he walked in my shoes for a full six years.

By then I was the oldest and the best of the boys who lived under Father Mosely’s roof. He told me so himself while he was busy punishing Joshua with the end of his cane. Sister Miriam had caught my brother and Abel Whitley stealing apples from the kitchen, and Joshua had called her a sour old maid.

Father Mosely shook his head while he delivered the punishment. ‘Samuel, why did the good Lord have your mother deliver two boys so very different?’ He took a good strong swing and I saw my brother wince. ‘One of you is a thief who won’t even learn to spell his own name.’ Thwack. ‘And the other one’s a saint, the very brightest and the best I’ve ever had the pleasure to teach …’ Thwack.

It was one of the Father’s favourite speeches, how the both of us were two sides of the same coin – one good, one bad, but always inseparable.

Father Mosely had his hand on Joshua’s neck as he pressed him down into the table to deliver his fifth and final blow.

‘Sir?’

‘Don’t interrupt me, Samuel. I will not spare the rod. In case you hadn’t noticed, there’s a war on and I won’t tolerate the stealing of food. Not ever.’ I held my tongue while he struck the last blow, then set my brother free. ‘Teach him, Samuel.’ He pointed us towards the door. ‘Teach him to work hard and obey the rules, I beg you, cos he’ll be the death of me if he can’t find it in himself to behave and get on with his work.’

Joshua was crying so hard with the rage and hurt of being hit that he couldn’t keep his mouth shut. ‘It was only an apple!’ he shouted, and I quickly took hold of his ear and turned him around before the priest got hold of him again. ‘I’m sorry, sir,’ I called out as I led him away. ‘I’ll try and teach him, sir, I will. Only he ain’t a bad boy. Really he ain’t. You know he’s got a good heart. He surely has, sir.’

But we both knew that weren’t true. Joshua had been bad since the day he was born, and I think Old Betty must have known it when she slapped him.

I did the best I could with him. I’d take him aside and read to him from books, sometimes getting him to copy down the words, though he never had the willingness to learn. He was always looking out the window, always had something else on his mind, and besides it weren’t only Joshua that I had to look after. Being the oldest meant I had to look out for all the kids cos Sister Miriam used to blame me when they did wrong. She’d tell me I shoulda stopped ’em, though I never knew how. Sometimes I didn’t even know right from wrong myself.

Anyway, everything changed when we got a new teacher at the school. Miss Priestly was her name and she was different to the others who we’d had before. She told me I might become a teacher, the same as her, on account of how I was good with words and how I liked to help the others in the class. She didn’t use those exact words to me, preferring to put it in the form of a question.

‘Samuel,’ she asked me one morning when we were all in class, ‘are you supposed to be the teacher here?’

‘No, ma’am.’ I answered her correctly.

‘Then why are you helping your brother with the work I set?’

I thought that would have been obvious but I didn’t say it – not wanting to make her look a fool – but the fact was that Joshua couldn’t do this particular task. He don’t have a love of words the way that I do. He don’t see the shape of ’em, and anyway, being that much younger than me, he’s got less of ’em to choose from.

She had read out the following example: ‘

The old man had never been known to change his mind. No. Not ever. The whole town knew him to be as stubborn as a mule.’

She asked us to think of something that was more stubborn than a mule and we were all having difficulty. I was sitting next to Joshua. ‘This is stupid,’ he whispered. ‘Everyone knows there ain’t nothing more stubborn than a mule.’

‘You don’t have to tell me,’ I whispered back, but Miss Priestly heard me. That’s when she asked me about whether I was the teacher or not and I said that I thought it was good to help others less fortunate than yourself. To my surprise she smiled at me, all gracious and golden and she agreed. ‘Yes, it is.’ Then she asked, ‘What word would

you

use instead of a mule, Samuel? I mean, if you wanted to illustrate stubbornness.’

I had to think fast, but I got one and I told it to her in the full sentence, as it would be used if I were writing it down.

‘The whole town knew him to be as stubborn as a screw that weren’t for turning.’

‘That’s perfect, Samuel,’ she said. ‘I think it does the job very well, but next time, please wait until you’re a teacher yourself before you interrupt my lessons.’

I knew she meant that one day I might be good enough to teach the class myself, though it wasn’t long before any hope I had of teaching at the orphanage disappeared for good.

*

Sister Miriam had asked that I sweep out the floors and polish ’em to a shine so good she could see her face in it. That’s why I was late for class. I had finished up and was walking across the dry red clay between the old school building and the main house. It was a Wednesday. That meant mathematics all morning and I could hear them children singing their nine times table out loud, their little voices drifting out across the air in the old yard. We were good at our tables and there weren’t a child in that room who didn’t know ’em, ’cept for maybe little Jessie, on account of his only being five years old and never having gone to school till he came to us only a few weeks before.

I was walking across to the classroom when I heard the chapel door fly open with a bang and I turned to see Father Mosely come running outside, his hands in the air and his cheeks all red with the rage that was in his heart.

He comes out howling. He’s taking big staggering strides

towards the centre of the dusty yard and his black gown is open at the front and billowing in the breeze, so he looks twice the size he really is.

When he drops his gaze from the heavens, I must be the first thing he sees because he points his finger at me, a finger so straight and deadly it could have been a gun, and he shouts out to me, ‘Samuel Jenkins, you come here to me now.’

His finger turns a full circle in the air till it points straight down at his black polished shoes, and he reels me in so tight I might as well be a fish on the end of his line, cos before I know it I’m standing there toe to toe, the top of my head nearly touching the bottom of his chin, close enough that I have to put my head back to get a look at his face.

He takes a deep breath. I can see the sweat glistening in the lines across his forehead as he takes hold of my ear and twists it tight till I’m up on my toes. He walks me swiftly into the chapel and I’m taking quick little steps like a pigeon, maybe five of mine to every one of his and I’m doing my best not to squeal out loud because my ear is sharp with the pain of being turned right around and inside out, though to be honest it hurts me more to be treated like my brother.

The air is cooler indoors than out. The chapel is dark and there’s the usual smell of polished wood coming from the pews that we pass on our way to the altar. Father Mosely lets go of my ear and points his finger at the table. ‘Look!’

And I do look. I don’t have no choice.

‘There is a turd upon the table of the Lord!’ he tells me, and I can see it clearly in the light from the candles, a solid log, all big and brown. I find myself sniffing the air but there’s no smell to it, at least not that I can tell. But still, there’s no mistaking what it is, and the fear grips my heart because there’ll be hell to pay for this. I know there will. I’ve

seen it before. There’ll be someone made to sit in the chair of judgement, same as there was when the golden cup of Christ was stolen and they found it in Billy Fielding’s box of things and he was taken down by the Devil himself.

There’s one of us here will pay the price.

Father Mosely squints up his eyes and his mouth goes all small and puckered. ‘Do you know anything of this?’

I shake my head.

He walks behind my back and stands the other side of me. ‘Is this some sort of joke?’

‘Who would do such a thing?’ I ask him.

‘Who indeed?’ Father Mosely speaks with some satisfaction, like at last we’re getting somewhere. His voice is hard and unafraid. He’s gonna find the boy who did this – I know he will cos he has before. ‘Is there anything you want to tell me, Samuel? I mean, before we ask the others. Now that it’s just you and me alone.’

I shake my head again. ‘I don’t know why these things keep happening, Father. Honest. I don’t know why people have to do bad things.’

Father Mosely walks behind the table and stands leaning over the turd. He’s looking down on it with his hands clasped together in front of him. ‘Another good question, Samuel. Why do people do bad things?’ He nods his head as though he has the answer. ‘It seems to me that we only have to be weak. Weak enough that when the Devil comes calling, we let him in. We let him put ideas into our heads. We let him put his poison in our hearts.’ He fixes me with one of his looks, the one he does where his eyes get bigger and he can see right through you. ‘Do you let the Devil in, Samuel? Do you? Is the Devil in your head?’

I immediately shake my head.

‘Are you sure, Samuel? Are you sure you don’t let the Devil in? Because I know you hear him – I know he calls to you to do bad things, same as he calls to all of us.’

I close my eyes, just in case Father Mosely can see the Devil in me, cos I know he’s in there somewhere. I can hear him whisper to me:

You do let me in, Samuel. I come in with your dirty thoughts.

Father Mosely puts a hand on my head. ‘Pray to the Lord, Samuel. Pray that He protects you from the words of Satan.’

And I pray to Him. I pray to Him. I pray to Him.

When I next look up, the bright blue eyes of Jesus Christ are staring down at me from the crucifix above the altar. Father Mosely is holding a white handkerchief and a cardboard box, a little smaller than a shoe box. It’s got the words,

Mrs Harbury’s Delicious Candy

on the side and there’s a drawing of a pink rosebud. He scoops up the turd with a handkerchiefed hand and places it inside the box. He puts the lid in place and then sweeps past me, making for the open doors, the cardboard box held up in front of him as he calls for me to follow. ‘Come, Samuel. Let us find out who is weak before the Lord.’

We go out into the yard, and the classroom is quiet as we climb the steps of the school porch. I run ahead and open the door for Father Mosely so that he don’t even have to break his stride before going through into the classroom.