My Life So Far (53 page)

Applauding soldiers who had sung for me at the antiaircraft gun outside Hanoi.

(Tony Korody/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

I am standing next to the antiaircraft gun, singing a Vietnamese song back to the soldiers right before I sit in the gun’s seat.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

This should have been a red flag.

Quoc isn’t with me today, but another translator tells me that the soldiers want to sing me a song. He stands close and recites the words in English as the soldiers sing. It is a song about the day “Uncle Ho” declared their country’s independence in Hanoi’s Ba Dinh Square. I hear these words: “All men are created equal. They are given certain rights; among these are life, liberty, and happiness.” I begin to cry and clap.

These young men should not be our enemy. They celebrate the same words Americans do.

The song ends with a refrain about the soldiers vowing to keep the “blue skies above Ba Dinh” free from bombers.

The soldiers ask me to sing for them in return. I am prepared for just such a moment. Before leaving the United States, I had memorized a song called “Day Ma Di,” written by students in South Vietnam who are against the war. I launch into it

con gusto,

feeling ridiculous but I don’t care. Vietnamese is a difficult language for a foreigner to speak and I know I am slaughtering it, but everyone seems delighted that I am making the attempt. Everyone laughs and claps, including me. I am overcome on this, my last day.

What happens next is something I have turned over and over in my mind countless times since. Here is my best, honest recollection of what took place.

Someone (I don’t remember who) leads me toward the gun, and I sit down, still laughing, still applauding. It all has nothing to do with

where

I am sitting. I hardly even think about where I am sitting. The cameras flash.

I get up, and as I start to walk back to the car with the translator, the implication of what has just happened hits me.

Oh my God. It’s going to look like I was trying to shoot down U.S. planes!

I plead with him, “You have to be sure those photographs are not published. Please, you can’t let them be published.” I am assured it will be taken care of. I don’t know what else to do.

It is possible that the Vietnamese had it all planned.

I will never know. If they did, can I really blame them? The buck stops here. If I was used, I allowed it to happen. It was my mistake, and I have paid and continue to pay a heavy price for it. A traveling companion, someone with a cooler head, would have kept me from taking that terrible seat. I would have known two minutes

before

sitting down what I didn’t realize until two minutes

after

ward. That two-minute lapse of sanity will haunt me until I die. But the gun was inactive, there were no planes overhead—I simply wasn’t

thinking

about what I was doing, only about what I was

feeling—

innocent of what the photo implies. Yet the photo exists, delivering its message, regardless of what I was really doing or feeling.

I realize that it is not just a U.S. citizen laughing and clapping on a Vietnamese antiaircraft gun: I am Henry Fonda’s privileged daughter who appears to be thumbing my nose at the country that has provided me these privileges. More than that, I am a woman, which makes my sitting there even more of a betrayal. A gender betrayal.

And

I am a woman who is seen as Barbarella, a character existing on some subliminal level as an embodiment of men’s fantasies; Barbarella has become their enemy. I have spent the last two years working with GIs and Vietnam veterans and have spoken before hundreds of thousands of antiwar protesters, telling them that our men in uniform

aren’t

the enemy. I went to support them at their bases and overseas, and will, in years ahead, make

Coming Home

so that Americans can understand how the wounded were treated in VA hospitals. Now by mistake I appear in a photograph to be their enemy. I carry this heavy in my heart. I always will.

T

he next day, departure day, Quoc says to me, “I think you need to prepare yourself. There are some U.S. congressmen who are asking that you be put on trial for treason.” It is my broadcasts over Radio Hanoi that have triggered the charges. He shows me the transcripts of Reuters news reports. The photo on the antiaircraft gun isn’t even the issue. It hasn’t yet appeared.

I

do not know if what I have seen is a true reflection of Vietnam’s reality. I know that there is selfishness, bitterness, pettiness, and violence in that small nation, as in all nations. I can understand and sympathize with the very different perceptions that our soldiers and POWs bring back with them. I know that best feet were put forward for my benefit (though that still doesn’t explain that schoolgirl, the Arthur Miller play, and the eyes of the peasants in bomb shelters even after learning I was American).

But I have seen the signposts; I have gained a new understanding of what strength is. Bamboo is the metaphor. Bamboo is deceptive. It is thin and willowy, it appears weak alongside the sturdy oak. But ultimately it is bamboo, with its flexibility, that is the stronger. For the Vietnamese, the symbol of strength is the image of many bamboo poles tied together. Bamboo holds a forgiving, flexible, softer energy that can exist in men and women. Vietnam is bamboo.

I am softening. Can it have been only two weeks?

I

n a screening room in Paris on July 25, I showed the forty-minute film to the international press. It had been roughly edited in Hanoi by Gérard Guillaume. My central purpose for making this controversial trip to Hanoi was to bring back documented evidence that the dikes I visited had been bombed, a charge the U.S. government was vehemently denying.

It seemed that every news service in the world was in attendance. Simone Signoret was there as well—my unique support system. The conference was hosted by the well-known French photographer Roger Pic. I do not recall if I carried the film out of Vietnam myself or if Guillaume had it shipped from Hanoi, but unfortunately, somewhere between Hanoi and Paris the sound track was erased, so I had to show it without sound.

I explained carefully how the antipersonnel bombs entered the dikes at a slant and exploded inside the mud walls, doing damage that was invisible in aerial photographs and difficult to repair. I explained that monsoon season was almost upon Vietnam and that if the weakened dikes should give way, hundreds of thousands of people would drown or die from starvation. It was all there on the screen: the rubble of the cities and hamlets I’d visited, the damage to the dikes, the craters, the close-up of where an antipersonnel bomb had entered the side of the dikes, and the beginning of my meeting with the POWs.

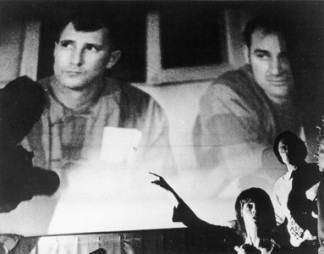

I showed the silent film again at a press conference in New York City—and that was the last I saw of it. It has disappeared. All that is left now is a photo that appeared in a number of magazines, of me at the press conference with the image of some of the POWs visible on the screen behind me. I do not know if the footage was stolen by spooks or lost innocently.

I told the press that I hoped people would realize, as I and other foreign visitors had, that the repeated bombing of civilian targets and dikes was intentional and must be stopped, and how the damage was concentrated where the dikes were most strategic. I told them that the POWs had given me messages for people back home, saying that they were afraid of being bombed and asking their families to support George McGovern for president. (I carried a packet of letters from POWs back to the States with me.)

At the Paris press conference, pointing to the film showing two of the POWs I met with.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

I was asked how I felt about being accused of treason. I tried to give a “bamboo”-type response and was quoted in the papers the next day saying, “What is a traitor? . . . I cried every day I was in Vietnam. I cried for America. The bombs are falling on Vietnam, but it is an American tragedy. . . . Given the things that America stands for, a war of aggression against the Vietnamese people is a betrayal of the American people. That is where treason lies . . . those who are doing all they can to end the war are the real patriots.”

T

om was waiting for me at the airport in New York City when I landed. He whisked me downtown to the Chelsea Hotel, where we holed up for the night like two refugees. I needed rest. I needed to be held.

Tom felt that because he had encouraged me to go, he was responsible for the trouble I’d gotten into, and he promised to try to make it up to me. Both of us realized that it had been a mistake for me to go alone. But I never felt that he was responsible. I hate buck passers.

As we lay in bed in our funky Chelsea Hotel room, I told Tom that I wanted us to have a child together as a pledge of hope for the future. We held each other and wept.

I

n the period of time right after my return, Representatives Fletcher Thompson (R-Ga.) and Richard Ichord (D-Mo.) accused me of treason. They said I had urged American troops to disobey orders and had given “aid and comfort to the enemy.” Representative Thompson, who was running for the U.S. Senate from Georgia, tried to subpoena me to testify before the House Internal Security Council (the updated version of the House Un-American Activities Committee made infamous in the fifties by Senator Joseph McCarthy), but his efforts were blocked. (He subsequently lost the election.) The committee issued me a subpoena, but when my lawyer, Leonard Weinglass, and I sent them a letter saying I was ready to appear, we were notified that they had adjourned the hearings and would contact us when a new date was set. We never heard from them again.

Soon thereafter, Vincent Albano Jr., chairman of the New York County Republican Committee, called for a boycott of my films.

I find it interesting that the government and news reporters knew that Americans before me had gone to North Vietnam

and

had spoken on Radio Hanoi. This was the first time, however, that the issue of treason was being raised.

T

he accusations about the bombing of the dikes that I along with others brought back from Vietnam caused an uproar within the administration. UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim held a press conference and said that he’d heard through private sources that the dikes had been bombed. Then Secretary of State William P. Rogers said: “These charges are part of a carefully planned campaign by the North Vietnamese and their supporters to give worldwide circulation to this falsehood.” Meanwhile, Sergeant Lonnie D. Franks, an intelligence specialist stationed at Udorn Air Base in Thailand was due to testify before the Senate Armed Services Committee about air force officers involved in bombing falsification of other targets. That investigation was eventually dropped, and only General John Lavelle, the commanding officer who had ordered (or overseen) the falsification, was held responsible.