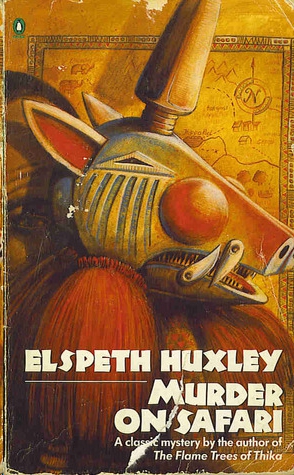

Murder on Safari

Authors: Elspeth Huxley

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Traditional British

MURDER ON

SAFARI

Elspeth Huxley

LMGEPRBT

MAlKSTREftM SERIES

Oxford, EnltalKI

Santa Barbara, California

Copyright й Elspeth Huxley 1938

First published in Great Britain 1938 by

Methuen Ltd

Published in Large Print 1988 by

Clio Press, 55 St. Thomas’ Street, Oxford 0X1 1JG, by arrangement with Elspeth Huxley.

All rights reserved

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Huxley, Elspeth, 1907

Murder on Safari

I. Title

823’.912(F)

ETOB1COKE

PUBLIC LIBRARIES

BRENTWOD

ISBN 1-85089-258-X

Printed and bound by Redwood Burn Ltd.

Trowbridge, Wiltshire

Cover designed by CGS Studios, Cheltenham

j brin

ForHea^^s\^^

FR1;CHAPTER

ONE

Vachell looked across the desk at his visitor with a slight sensation of surprise. He’d never met a famous white hunter before, and he felt that a member of such a romantic profession ought to be big and husky and tanned, and to dress in shorts and a broad-brimmed hat. Danny de Mare was at the top of his profession but he didn’t look husky at all. He was a rather small, slight man, with broad shoulders that dwarfed his height, and small hands and feet.

“Sit down, Mr de Mare,” Vachell said. “I read somewhere you’d gone up to the Western frontier on a job, but I guess I got the dates wrong.”

Danny de Mare sat down in a high-backed chair and faced Vachell, Superintendent of the Chania C.I.D.3 over an untidy, littered desk. His face was lean and sallow and a long, beaky nose gave it a bird-like look. His expression was alert, like an animal ready to pounce if anything moved unexpectedly; he reminded Vachell of a small, compact

i

hawk. His thick, dark hair, brushed until it shone, was grey at the temples. He wore a well-cut grey flannel suit with a white pin-stripe, a blue-andwhite spotted tie, and carried a soft grey hat.

“You were right,” he said. “I got down to

Marula late last night, and I go back to the

Western frontier district tomorrow. My safari’s camped on the Kiboko river, safely at anchor, I hope. As a matter of fact, I came to see you.”

‘ Vachell slid a box of du Mauriers over the table and crossed his lanky legs. He was a tall, lean young Canadian, with sandy hair brushed back

from a high-cheeked, bony face, and a large

mouth which seemed ready to expand at any

moment into a friendly grin.

“Anything serious?” he asked.

“There’s been a burglary, Lady Baradale —

she’s rich as Rockefeller, and paying for the whole outfit - says she’s lost a whole sackful of jewellery.

I’ve got a description of it here. She puts the value at thirty thousand.”

He took a sky-blue envelope out of his pocketbook and handed it over. A coronet was embossed

on the flap and inside were two sheets of notepaper with “On Safari, Chania” in red letters at

the top as an address. Vachell read through the list without speaking and rubbed the side of his nose with a nicotine-stained finger.

“She sure must like to put on the dog,” he

remarked. “What does she want with all this stuff on the Western frontier? There must be some

2

onative chief up there who’s going to have a coronation.

So some guy’s swiped the lot, has he?”

“Or she,” de Mare said. He spoke tersely,

giving every word its full value, in a pleasant baritone voice. There was nothing aggressive

about him, but his whole manner was quietly selfassured.

I’d better tell the story properly. Lady

Baradale sent for me the day before yesterday, about eight p.m. She said she’d just opened the portable safe she keeps in her tent to get out some jewels to wear at dinner, and she found that practically everything had gone.

“She was in a frantic state, of course. I wanted to hold an inquiry there and then, but she turned that down flat; said, I suppose with truth, that the thief had probably had all day to hide the stuff and all East Africa to do it in, and that it was better policy to say nothing and keep him guessing until the police arrived. So I agreed to drive down to Marula next day. I got in after midnight, and came here first thing in the morning.”

The Superintendent lit a cigarette and stared thoughtfully out of the open window. Sunlight flooded the small square of lawn that lay between his window and the row of eucalyptus trees that sheltered the road. Africans strolled without haste and apparently without objective along the highway.

The bark of a sergeant’s voice came to his

ears from the parade ground behind the headquarters of the Chania Police.

‘What’s your opinion?” he asked his visitor.

3

“She’s not the sort of woman to mislay thirty thousand quid’s worth of jewels through carelessness.

Enormously rich American — her money

comes from things like caffeineless coffee and tanninless tea, I believe — but she’s like God and the sparrow: knows every dollar by name. She

always locks her jewels into this travelling safe, and keeps the key herself. She told me that even her maid isn’t trusted with the key. But someone must have pinched it, because the safe wasn’t forced. There’s only the one key apparently, and you can’t cut duplicates on safari.”

“Who’s on the roll-call in this safari outfit?”

De Mare smiled. He had very white teeth, and

the smile made his face come alive. Vachell

noticed his eyes for the first time: light brown and large, with long, curved lashes. He looked much more human when he smiled.

“Uncle Tom Cobley and all,” he said. “Lady

Baradale first; she pays. I’ve told you about her.

Then Lord Baradale; he takes pictures, and plays about with camera gadgets, and thinks out Heath Robinson inventions. His daughter by a previous marriage, Cara Baradale. One of those hardboiled, prickly girls; I don’t know what she does.

Her fiance. Sir Gordon Catchpole; he decorates London interiors, I believe. Then there’s Lady Baradale’s maid, Paula, and Rutley, the chauffeurmechanic.

He’s as pleased with himself as a

peacock — he once had a small part in Hollywood, I believe, in fact Lady Baradale picked him up 4

there Ч and he’s got a filthy temper, but I must say he’s a good mechanic. That’s all the Europeans.

Then there’s a whole tribe of native

retainers Ч gun-bearers, trackers, cooks, personal boys, drivers, skinners, and just plain porters. No expense spared.”

“Do you look after all those babies singlehanded?”

Vachell asked.

“There’s a second hunter, of course Ч a young fellow called Luke Englebrecht, a Dutchman. A newcomer to our racket, but he knows his stuff; he was born in Chania and brought up rough, and it’s as natural to him to shoot as to breathe; his only trouble is, he’s a bit of a butcher. And then there’s me. Oh, and Chris Davis Ч you’ve heard of her, I expect. She brought her plane along to join the three-ring circus.”

“The dame who spots big game from a plane

and then comes back to tell on them?” De Mare nodded. “That’s always seemed kind of mean to me. Well, that’s nine Europeans Ч four to hunt and five to smooth their path through the bush.

How about the African staff?”

“I don’t think any of the gun-bearers or trackers are likely to have turned into jewel thieves. It isn’t as though the safe was forced; whoever did the job borrowed the key. I suppose it’s possible that one or two of the personal boys might be mixed up in it. Lord Baradale’s pet valet, a Somali called Geydi, for instance. I don’t trust him a yard.

When it comes to conceit he makes Rutley look 5

like a small child, and he’s ultra-sophisticated; he’s even been to England. But it’s no good my sitting here and trying to give you potted biographies of all these people. You’d better come up

to the camp and see them for yourself.”

Vachell smoked for a few moments in silence,

his eyes on two natives squatting on their hams under a gum tree across the lawn and tossing

coins. The chance of an assignment in the Western frontier district, away beyond the civilized parts of the colony, seemed too good to be missed. He was new to his job, to the colony, even to Africa. It would break new ground.

~ “I might get up there,” he agreed, “so long as it isn’t a wild-goose chase.”

“There’s one thing in the police’s favour,” de Mare said. “The stuff must still be up there, hidden somewhere in or near the camp. No one

has left in the last week, so there’s been no chance to get it away.”

“What about mail?”

“We send a lorry into Malabeya at intervals for supplies, but we haven’t done so since the theft.

It’s the nearest Government post, about a hundred miles away — too far to walk to post a letter. Lady Baradale’s got a suggestion about police investigation.

She thinks you’d find out more if you came

under false pretences — if no one knew you were a detective. Then people wouldn’t be so much on their guard.”

“What do I pretend to be?” Vachell asked. “A

6

man come to read the gas meter, or a college boy trying to sell Lady Baradale a subscription to the Saturday Evening Post to help earn my way

through school?”

De Mare looked grave and shook his head.

“Nothing so respectable. She wants to get rid of Englebrecht. She’s got nothing against him as a hunter; it’s a personal matter. She wants him to fade out and you’re to take his place, disguised as a white hunter. I could manage for a week without assistance, I think. I expect you’re a good shot, and if it came to a pinch you could deputize. How does the idea appeal?”

“It appeals like a swim in a pool full of starving crocodiles,” Vachell answered. “What do I do

when I meet a herd of elephants head-on? Make a noise like Sabu the elephant boy, or show an

honorary membership ticket in the White

Hunters’ Association? I’m here to chase criminals, not to be chased by wild animals.”

“We wouldn’t send you out after anything

savage,” de Mare said reassuringly. “A kongoni or two at the worst. A second hunter’s job is mostly checking over Fortnum and Mason chop-boxes

and writing requisition forms for new supplies of shoepolish, these days. You might pick up some sort of a lead, if you come as a hunter. If you come as yourself no one will want to gossip to you. I propose to leave Marula at four a.m. tomorrow.

I’d be delighted to take you if you decide to come.”

De Mare stood up, adjusting his tie. Again

Vachell felt irrationally surprised that he should be so small, slender and spruce.

“You’ll want rifles and some camp kit,” the

hunter added. “I’ll help you choose them — this afternoon, if you like.”

“I’ll have to think it over,” Vachell said.

De Mare nodded, and made towards the door.

“Lady Baradale will pay the extras, of course,” he said. “I’ll be in the lobby of Dane’s at two-thirty, if you want to do any shopping.”

His step, as he walked out, was light and

springy. The word jaunty came into Vachell’s

mind. Its slightly Edwardian flavour seemed to fit the hunter well.

Vachell had heard of him often, but had never run across him before. There were only three

white hunters in East Africa, it was said, worth a salary of г200 a month, and de Mare was one. He was middle-aged now — round about the fifty

mark — but they said he was as skilful a hunter and as infallible a shot as ever. He knew the game districts inside out, from the Sudan to Rhodesia.

He had other assets, too, just as important on modern safaris — social assets such as ease of manner, ability as a raconteur, and attraction for women. He wasn’t good-looking, Vachell reflected, but from all accounts women fell for him

like ripe coconuts. He had been married once, but there had been a divorce.

He had a reputation for reckless courage and for 8

a sort of bravado which belonged to a past age and generation. He had speared a lioness from a pony’s back, and once the Masai had permitted him to join a warrior’s lion hunt, armed with a long shield of buffalo hide and a native spear. The hunted beast had charged the line between de Mare and his Masai neighbour and had fallen a yard from either with two spears, the white man’s and the warrior’s, quivering in its body. He had hunted elephant in Abyssinia in the Emperor Menelik’s days, and once, according to legend, entertained an Ethiopian chieftain, who had been sent from Addis Ababa to arrest him for poaching ivory, to a sumptuous feast of raw meat in his tent, while the tusks for which the potentate had unsuccessfully searched all day were buried underneath the table at which the banquet had been held.

- There were stories, too, of his extravagance.

Sometimes, after a safari, he would spend a

month’s salary on a couple of wild parties in Marula, and he was said to be always in debt. He once got out of the country wearing a red beard and a turban, having disguised himself as a Sikh merchant and joined a party of his own creditors travelling down to the coast to intercept his flight.