Murder by Numbers (24 page)

Authors: Kaye Morgan

“Well,” he said, “as soon as you come up for airâ”

Michael bent to plant a kiss on the top of her head, then abruptly reared back with a loud “Ah-

choo

!”

“Looks like you're the one who needs air.” She ruffled her hair. “You never know where dog dander will collect, I guess.”

“As long as it's the dog,” Michael told her, “and not you.”

“Perish the thought,” Liza replied, with a sidewise smile. “Not when things are beginning to get interesting.”

Too Hard?

Take It Easy!

Do you sometimes wish there was a lemon law for sudoku? Or at least that some kind of truth in advertising applied to puzzles?

Rating the difficulty of sudoku stands as a thorny issue for prospective puzzle solvers. You're probably encountered it. Perhaps you're traveling, pick up a newspaper, and find a sudoku puzzle claiming to be a great challenge. Yet you blow right throughâit's way too easy. Or maybe there's one listed as moderate, but it refuses all your best techniques!

We have to face the sad fact that while crossword puzzles developed a fairly standard system of rating difficulty, sudoku hasn't. Of course, crosswords have been around a lot longer. Perhaps by the end of this century, sudoku scholars will write condescending pieces on this whole controversy. Here and now, however, the rating question is enough to cause civil war in Sudoku Nation.

At least the competing schemes make for some colorful language. Our British cousins, especially, come up with interesting grades. Starting off with “Gentle,” they quickly escalate to “Diabolical,” “Fiendish,” or “Horrible.” Not to be outdone, other representatives of Sudoku Nation have come up with ratings like “Maniac,” “Nightmare,” “Insane,” “Evil,” and “Mind-bending.”

Judging by the success of these titles, one thing seems clearâsudoku solvers must have a perverse, even masochistic, streak. When I first got this job, I thought I'd cash in on that with my G-ratings system: “Grungy,” “Ghastly,” “Grotesque,” and “Godawful.” For some reason my editor killed that idea, along with my next set of ratings: “Devious,” “Tricky,” “Are you Kidding?” and “I Want My Mommy!”

Hey, it's no worse than the suggestion from one of the programmers at Solv-a-doku for the highest difficulty level: “Captain, It's Goin' to Blow!”

The taglines may be funny, but they're also imprecise. Difficulty remains all in the eye of the beholder. One solver's “Fiendish” may be another solver's “Moderate.” So how can we get a rational handle on the problem?

In the beginning, people tended to equate difficulty with the number of clues in a puzzle. It seemed logical enough. The fewer clues in the sudoku, the more spaces to be filledâand the more work for the solver. Unfortunately, that logic isn't necessarily consistent.

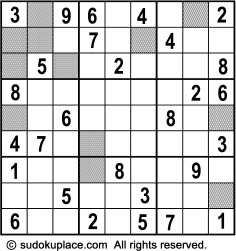

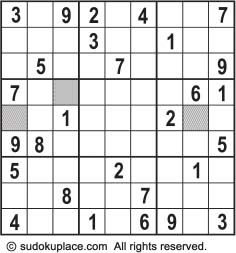

Mark Danburg-Wyld, a fellow Oregonian and sudoku colleague with puzzles in several newspapers, presents the shortcomings of the clue-counting method on his website, www.sudokuplace.com, and he's graciously allowed me to use two of his puzzles.

As you can see, the pattern is the same for both puzzles, the number of clues the same, and the upper left-hand box is identical. But what happens when you start scanning the clues for answers? The shaded spaces show how many results a solver can get.

Do the math, and you could say that Puzzle Two seems about four times harder than Puzzle One. So much for all clues being equal. Go to Mark's site for a discussion of the way he maps subsequent moves to generate his own rating system.

People who develop sudoku-solving programs often brag about how few microseconds it takes for their creations to grind out a solution. But these programs usually use the brute-strength, trial-and-error mode allowed by the computer's speed. That's not the way human beings solve sudoku.

More recently, though, programmers have attempted to mimic human logic, coming up with computer versions of the various solving techniques. By assigning point scores to each technique and additional points for repetitions, they can actually come up with numerical ratings for solved sudoku. A simple exercise that requires only hidden singles and listing candidates might get around 50 points. Puzzles that demand higher-order techniques like naked pairs and Row and Box/Column and Box interactions might score around 100. A puzzle that needs an X-wing to solve it might come in around 500. Repeated applications of X-wing or swordfish techniques could push a score up past

1000.

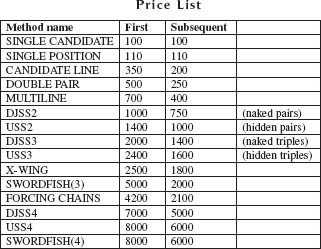

A participant at the Sudoku Programmers Discussion Site proposed the following price list.

The terminology may be different, but you can figure it out (or look it up). After running a number of

London Times

puzzles on his solver, the participant reported an average score of 4600 for “Easy” puzzles, and average of 5200 for “Mild,” 5600 for “Difficult,” and 6500 for “Fiendish.”

The sudoku section at the playr.co.uk site uses several numbers to rate its puzzles. First, the site organizes eighteen techniques into five levels of difficulty from simplest to most esoteric. Then they count how many separate techniques from each level went into solving a puzzle. A “Hard” rating might come in a 1.3.2âone first-level, three second-level, and two third-level techniques required. An “Extreme” puzzle might get a 2.5.2.2.1 rating.

Both systems are interestingâone counts successive uses of a technique, while the other offers a scorecard of the number of techniques used.

Interestingly, farther along in the string on the Sudoku Programmers Discussion Site, the same participant raised another yardstick of difficultyâthe number of valid moves available for each step along in the puzzle. Maybe I should send him the URL for Mark's site.

Moving away from the computer world, a new movement has arisen in the past few years using human solvers to rate a puzzle's difficulty by the amount of time they take. It makes senseâafter all, this is the way competitive sudoku is scored, and more and more competitions seem to be cropping up. There's even a book out offering puzzles with a time score to beatâsomething to make even “Easy” puzzles more challenging.

Yet even with a time-based rating, questions arise, as one participant on the Sudoku Addicts Discussion Board pointed out. Mightn't a more accurate rating scale take into account the average time along with number of puzzles submittedâand the number of incorrect puzzles?

I have to confess, my favorite response among all the discussions of difficulty was the participant who admitted that he never looks at scores, number of stars, or descriptive ratings. He just does the puzzle.

If you can take your sudoku one at a time, without getting snotty or worrying about bruised egos, at least you can enjoy the fun of the chase, whether you solve it or not. After all, for most of the folks in Sudoku Nation, puzzles aren't a job. Aren't we supposed to have fun?

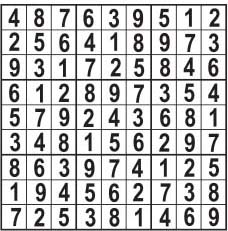

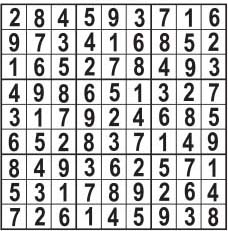

Puzzle from Chapter 2

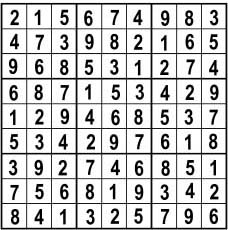

Puzzle from Chapter 7

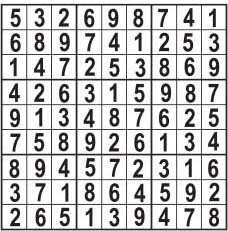

Puzzle from Chapter 12

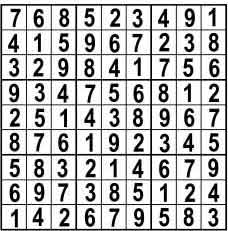

Puzzle from Chapter 14

Puzzle from Chapter 20