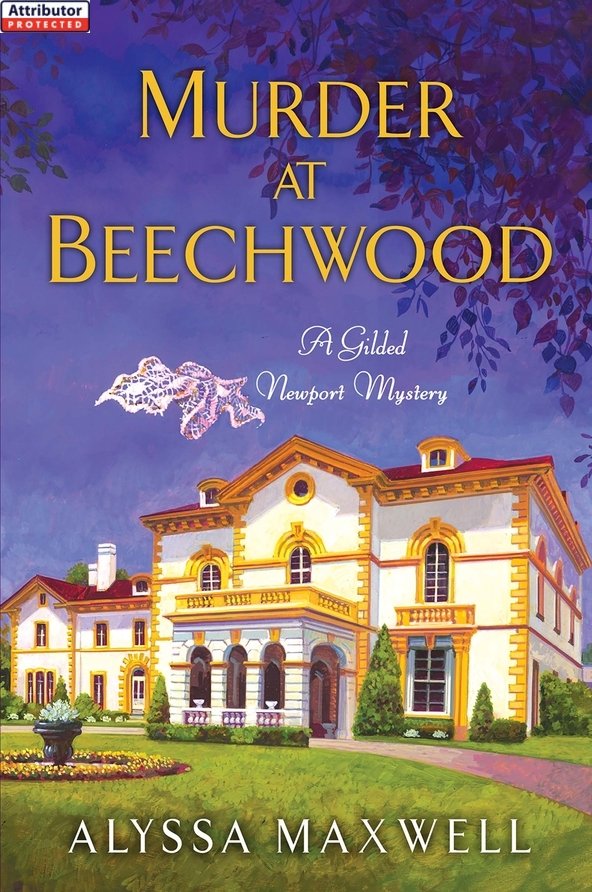

Murder at Beechwood

Read Murder at Beechwood Online

Authors: Alyssa Maxwell

P

RAISE FOR

A

LYSSA

M

AXWELL

AND

H

ER

G

ILDED

N

EWPORT

M

YSTERIES

!

RAISE FOR

A

LYSSA

M

AXWELL

AND

H

ER

G

ILDED

N

EWPORT

M

YSTERIES

!

Â

Â

Â

M

URDER AT

M

ARBLE

H

OUSE

URDER AT

M

ARBLE

H

OUSE

Â

“Maxwell again deftly weaves fictional and real-life

characters into her story.”

characters into her story.”

Â

â

Publishers Weekly

Publishers Weekly

Â

Â

M

URDER AT THE

B

REAKERS

URDER AT THE

B

REAKERS

Â

“Intriguing characters and a solid murder mystery.”

Â

â

RT Book Reviews

RT Book Reviews

Â

“Will keep you guessing.”

Â

âHistorical Novels Reviews

Books by Alyssa Maxwell

Â

Â

MURDER AT THE BREAKERS

MURDER AT MARBLE HOUSE

MURDER AT BEECHWOOD

MURDER AT MARBLE HOUSE

MURDER AT BEECHWOOD

Â

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

A Gilded Newport Mystery

M

URDER

A

T B

EECHWOOD

URDER

A

T B

EECHWOOD

ALYSSA MAXWELL

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

To my beautiful daughters, Sara and Erin,

with all my love. You might not have lived in

Newport, but you are Newporters

all the same. I'm so proud of you both.

with all my love. You might not have lived in

Newport, but you are Newporters

all the same. I'm so proud of you both.

Chapter 1

Newport, Rhode Island, June 29, 1896

Â

I

sat up in bed, my heart thumping in my throat, my ears pricked. I'd woken to a high-pitched keening, an eerie, unearthly sound that gathered force in the very pit of my stomach. There had been no warning in last night's starry skies and temperate breezes, but sometime in the ensuing hours a storm must have closed in around tiny Aquidneck Island. I knew I should hurry about the house and secure the storm shutters, yet as I continued to listen, I heard only the patient ease and tug of the ocean against the rocky shoreline, the sighs of the maritime breezes beneath the eaves of my house, and the argumentative squawking of hungry gulls flocking above the waves.

sat up in bed, my heart thumping in my throat, my ears pricked. I'd woken to a high-pitched keening, an eerie, unearthly sound that gathered force in the very pit of my stomach. There had been no warning in last night's starry skies and temperate breezes, but sometime in the ensuing hours a storm must have closed in around tiny Aquidneck Island. I knew I should hurry about the house and secure the storm shutters, yet as I continued to listen, I heard only the patient ease and tug of the ocean against the rocky shoreline, the sighs of the maritime breezes beneath the eaves of my house, and the argumentative squawking of hungry gulls flocking above the waves.

With relief I eased back onto my pillowsâbut no. The sound came againâlike the rising howl of a growing tempest. Throwing back the covers, I slid from bed and went to the window. With both hands I pushed the curtains aside.

And stared out at a brilliant summer dawn. Long, flat waves, tinted bright copper to the east, mellowed to gold, then green, and then a deep, cool sapphire directly beyond my property. The sky was still a somber, predawn gray, but clear and wide, with a few stars lingering to the west. Like polished silver arrows, the gulls dove into the water with barely a splash and swooped away to enjoy their quarry.

I could only conclude I had been dreaming, even when I'd thought I was awake. Well, I was certainly awake now. I grabbed my robe, slid my feet into my slippers, and quietly made my way downstairs.

I needn't have muffled my footsteps, for as I entered the morning room at the back of the house I found Katie, my maid-of-all-work, as well as Nanny, my housekeeper, already setting out breakfast. The inviting scents of warm banana bread and brewing coffee made my stomach rumble.

“You're both up early,” I said.

“Mornin', Miss Emma,” Katie replied in her soft brogue.

Nanny's plump cheeks rounded as she bid me good morning, her half-moon spectacles catching the orange flame of the kerosene lantern. “Something woke me. I'm not quite sure what.”

“That's so oddâme as well.” I picked up the small stack of dishes and cutlery on the sideboard and carried them to the table, noticing the web of small cracks in the porcelain of the topmost plate. Katie looked at me uncertainly, then half shrugged and made her way back to the kitchen.

She had been in my employ for a year now and had yet to grow accustomed to the informal machinations of my household. At Gull Manor we never stood on ceremony; there was no strict order of things, but rather a daily muddling through of tasks and chores and making ends meet. That was my lifeâby my choice and by the gift of my great-aunt Sadie, who had left me the means to lead an independent life.

Part of that gift included this house, a large, sprawling structure in what architects called the shingle style, with a gabled roofline, weathered stone and clapboard, mullioned windows framed in timber, and enough rooms to house several families comfortably. Set on a low, rocky promontory on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, Gull Manor was a very New England sort of house, one that seemed almost to rise up from the boulders themselves and have been fashioned by the whim of rain, wind, and sea. Yes, it was drafty, a bit isolated, and required more upkeep than I could afford to maintain it on the proper side of shabby, but it was all mine and I loved it.

Katie returned with a sizzling pan of eggs, and I asked her, “What about you, Katie? What brought you down so early?”

“Oh, I'm always up before the sun, miss. A leftover habit from being in service.” She placed the frying pan on a trivet on the sideboard and whirled about. “Oh, not that I'm not still in service, mind you. . . .”

“It doesn't always feel like it, though, does it?” I finished for her.

“No, miss. And for that I'm grateful. Now . . . I'll go and get the fruit. . . .”

Nanny, in a faded housecoat wrapped tight around an equally tired-looking nightgown, heaped eggs and kippers on a plate, placed a slice of banana bread beside them, and went to sit at the table. I did likewise, and when I'd settled in and picked up my fork, I hesitated before taking the first bite. “Have you seen our guest yet this morning?”

Nanny shook her head. “That sort doesn't rise with the sun.”

“Nanny! That's unkind. Please don't refer to Stella as âthat sort.' We agreedâ”

“We agreed, but I still worry that you're crossing a line, Emma. Out-of-work and disgraced maids are one thing, but . . .” She pursed her lips together.

“Prostitutes are another,” said a voice behind me.

Nanny glanced beyond my shoulder and I twisted around to see the figure standing in the doorway. Stella Butler wore my old sateen robe buttoned to her chin. Her ebony hair, tamed in two neat plaits, hung over each shoulder, making her look anything but a jaded woman. The bruises with which she had arrived at Gull Manor had faded, thank goodness. High cheekbones and slanting green eyes marked her a beauty, but today that beauty struggled past obvious fatigue and the downward curve of her mouth. She met our gazes with defiance, but the spark quickly died. She bowed her head and released a sigh.

“I'm sorry. I'm grateful to you, Miss Cross. I promise I won't stay long and I'll pay you for every scrap of food I eat.”

I stood and pulled out the chair beside my own at the round oak table. I gestured to the well-worn seat cushion. “You'll stay as long as you need, and as for payment, I'm sure we'll work something out, something mutually beneficial.”

Nanny harrumphed. Without another word Stella scooped up a small portion of eggs and a slice of banana bread I deemed too thin, and returned to the table. I was about to admonish her to take more, that she needed to keep up her strength, but thought better of it. Stella obviously had her pride, and if she was going to carve out a better life than the one she'd been living, she would need pride as much as strength.

“I'll be back in a moment,” I told them. “I'm going to see if the newspaper came yet.”

“I would think the storm kept the delivery boys from venturing out at their usual time,” Stella said without looking up.

“You too? This has been the strangest morning.” I glanced out the window. The sun had fully risen, gilding our kitchen garden and the yard beyond. A few fair-weather clouds cast playful shadows over the water. With a shrug I headed for the front of the house, my slippers scuffing over the floor runner. Ragged edges and the occasional hole suggested the rug needed replacing, but it would be some time yet before I could justify the expense.

It was as I reached the foyer that the wind suddenly picked up again, sending an unnerving shriek crawling up the exterior façade to echo beneath the eaves. I hadn't been dreaming. What kind of a strange storm was this?

Bracing for a blustery onslaught, I opened the front door.

“Nanny! Nanny!” I shouted and fell to my knees. Here was no gale battering my property, or any other part of the island on which I lived. The keening and the cries I'd heard, that had yanked me from sleep, were not those of a summer squall.

They were those of a baby, tucked into a basket and left on my doorstep.

Chapter 2

“L

and sakes . . . What on earth?”

and sakes . . . What on earth?”

Nanny bent over me as I gathered blankets and whimpering child into my arms. Gently I lifted itâhim? her?âfrom the basket and stared in mute astonishment at the little face, red and wrinkled and damp from tears.

Watching from the doorway, Katie gasped and Stella let out a whispered oath. The silence that followed declared them as shocked as I.

“Oh, Nanny,” I said, staring at this tiny person in disbelief, “how long can it have been here? I heard it crying . . . but I didn't come. I never thought . . . Who would leave a baby on a doorstep?”

Nanny being Nanny, she placed her hands on my shoulders and helped me to stand. “Let's get this child in the house and see if we can't figure out what on earth is going on here.”

Â

The first thing I did, after handing the child over to Nanny, was run to the alcove beneath the staircase, where my uncle Cornelius had had a telephone installed for me. First, I telephoned Jesse Whyte, a detective with the Newport police and an old friend. He wasn't at the station, however, and when the man on the other end of the wire asked if I wanted to leave a message, I hesitated, then said I'd call back and quickly hung up.

I stood for a moment with my hand on the ear trumpet where it dangled from its cradle. Why had I been unforthcoming with a member of the police? Didn't I have to report this incident? Yet the very thought of revealing too much too soon, and to the wrong people, raised a prickly warning at my nape. I trusted Jesse Whyte implicitly, and I would wait for him before making my next move, whatever that would be.

However, there was one other person I trusted. I lifted the ear trumpet and turned the crank.

“Operator. How may I place your call?”

“Good morning, Gayla.” I knew I would have to trade pleasantries before I could proceed. Gayla and I had known each other all our lives.

“Oh, hello, Emma. How's everyone out your way?”

“We're just fine, Gayla, thanks.” I noticed my foot tapping and held it still. “And you?”

“My father's gout is acting up again.”

“Sorry to hear it.” She started to go on, but my impatience was building. “Gayla,” I interrupted, “would you connect me with Dr. Kennison, please?”

“Oh, dear. No one's sick, are they?”

“No, no. It's . . .” I thought a moment, crossed my fingers, and improvised. “Nanny is due for her appointment, is all. But she's fine. So . . . please, Gayla.”

“All right. Hold the line. . . .”

The next half hour passed in a blur of activity. Katie had carried the basket into the house and discovered a feeding bottle and containers of Mellin's powdered baby milk that had been tucked in with a small supply of diapers.

“At least someone thought of his immediate needs,” she said, though her tone implied that this

someone

hadn't risen much in her estimate. She proceeded to loosen the swaddling and peeked inside. “He's a boy!” Delight twinkled in her eyes.

someone

hadn't risen much in her estimate. She proceeded to loosen the swaddling and peeked inside. “He's a boy!” Delight twinkled in her eyes.

Meanwhile, Stella had gone upstairs to rummage through the spare bedrooms for light blankets and extra linen we could fashion into swaddling and yet more diapers. Aunt Sadie never had children, so there would be no ready supply of baby necessities stored away in a cedar chest in the attic. As Nanny sagely pointed out, you never could have enough linen on hand where an infant was concerned, and at this point we didn't know how long our visitor would be staying with us.

One thing was certain: This child had been dropped off once, and it wasn't going to happen again, at least not on my watch. I wouldn't be leaving him at the police station or packing him into my buggy for a drive up to St. Nicholas Orphanage in Providence. Gull Manor had already proved itself a haven for strays, and this poor mite was nothing if not that.

In the parlor, I reclaimed him from Katie's arms and sat with him on the sofa. Being no stranger to infants, Nanny had boiled water and mixed a quantity of the Mellin's, so that when he began whimpering again she had the bottle cooled and ready. “By my estimate,” she said, twisting to tighten the seal of the rubber nipple, “he's no more than two or three weeks old. A month at the most.”

“So young!” Stella entered the parlor and deposited the results of her search on the sofa. “Who would do such a thing?”

“Someone desperate,” I replied, looking down as if speaking to the child nestled in my arms. “Someone who had no other choice.”

My gaze strayed from the child to Katie, who sat on the floor at my feet, her face turned up to me.

“Someone with nowhere else to turn,” she whispered. Tears filled her eyes and my heart broke for her, for I knew she was remembering the unborn child she had lost a year ago last springâthe child who had been forced upon her by an unprincipled youth, and who had resulted in her being fired from her position at The Breakers, the home of my Vanderbilt relatives on nearby Ochre Point.

While Katie blinked her tears away, I carefully tipped the bottle and touched the nipple to a pair of rosebud lips. Those lips immediately opened, drew the nipple in, and latched on with a strength that startled me and made me grin. Sucking noises filled the silence.

“Desperate or not, it's horrible to abandon a baby on someone's doorstep.” Stella tossed her head, sending one braid swinging over her shoulder. “Only a selfish, wicked person would do such a thing.”

Nanny turned to her with a patience she hadn't previously shown the young woman. “You don't understand. The person who left this child knew about Gull Manor. That's why she came here. It's why

you

knew to come here. Because Emma would never turn away anyone who needed her help. That's what Gull Manor means here in Newport.”

you

knew to come here. Because Emma would never turn away anyone who needed her help. That's what Gull Manor means here in Newport.”

“That's right, you're safe here,” I said, this time intentionally speaking to the child. He took no heed, too intent on drawing nourishment into his tiny body. All the while, the bottle moved subtly against my palm to the rhythm of each greedy suck. “You may be small, but you're determined, aren't you?”

By the time the milk was nearly gone, those little greenish blue eyes, which had been staring up into mine as if to impart some vital wisdom, began to droop. The others had settled around the room to watch, but now Nanny came to her feet.

“Unless I miss my guess, this little one is in need of a diaper change and a nice long nap.” She reached for a folded linen square from the top of the pile we'd made. Stella had also managed to gather an assortment of safety pins, which she'd deposited on the sofa table.

With a twinge of panic it struck me that I had never changed a diaper in my life. In fact, this was the first time I'd fed a baby, and while he had really done all the work, I surmised such would not be the case with diaper changing.

“I'll do it.” Katie accurately interpreted my hesitation. She stood and reached for the baby. “I'll take him into the kitchen.”

I hesitated in handing him over. “Have you ever done this before?”

She showed me an indulgent smile. “I'm the second oldest of six, Miss Emma.”

“I'll help.” Stella followed her out of the room, surprising me. I hadn't previously suspected her of harboring maternal instincts. Or was that simply my preconceived prejudice, based on her life previous to arriving at Gull Manor? I loathed to think I'd been judging Stella, that I had in any way blamed her for falling into the oldest profession. As Aunt Sadie had taught me, a woman did what she must to survive, and it behooved the more fortunate among us to help where and when we could.

“What are we going to do?” I asked Nanny once we were alone.

“Do?” She tucked a wiry gray curl into her kerchief. “I believe we're doing it.”

“Yes, but, Nanny, we can't keep this baby.”

“Can't we? Whoever it belongs to either doesn't want him or can't keep him.”

“But even if that's true, there could be relatives who would take the child in if they knew he existed. We can't assume no one wants him.”

“Then what do you propose we do?”

Before I could reply, Katie called out my name from down the corridor. A moment later she passed through the doorway with one arm outstretched, a bit of lace dangling from her fingers. “Look, Miss Emma. This was tucked into the baby's blanket. I don't know how we didn't see it sooner.”

“Where is he? Did you leave him alone?” Frissons of alarm shot through me.

She frowned slightly. “Of course not. Stella's finishing up with his diaper. Seems she grew up with four younger brothers and sisters.”

“Oh, yes, of course. I'm sorry.” I wondered at my strong and instant reaction to the idea of Katie having left the baby unattended, that the person in whose charge I had left him had returned without him. It seemed I harbored some surprising maternal instincts as well, and the smile dancing in Nanny's eyes told me she'd noticed, too.

I held out my hand. “Let me see what you've got there.”

Katie dropped into my palm an embroidered handkerchief edged with laceâno ordinary lace, mind you, but an intricate pattern shot through with golden silk threads. Puzzled, I searched for an initial worked into the embroidered design, but there were only flowers.

“This was costly,” I said.

Katie nodded her agreement. “Do you suspect the mother might be a lady of quality?”

“I don't know. I suppose a maid could have gotten hold of this handkerchief, but the question would be why?” I fingered the tiny yellow and pink flowers and curling pale green vines embroidered on the linen portion of the handkerchief. This was meant to dangle from a manicured hand during a ladies' tea or luncheon, or to ward off a sheen of perspiration during a garden party. “This isn't here by chance. I'm fairly certain of that.”

“A clue, then,” Nanny said, reading my thoughts as she so often did. “Someone wants us to know where this baby came from.”

“A rather obscure clue, though. With no initial or crest of any sort, this could belong to anyone and have come from anywhere, even off island. For all we know, someone brought the child over on the morning ferry.”

“Not so, at least not this morning.” Nanny reached to take the handkerchief and crossed the room to hold it in the brighter light of the front window. “We all heard what we believed to be a squall before sunup. The morning ferry wouldn't have arrived yet.”

Katie's hand flew to her throat. “You don't suppose the poor lad was outside all night?”

“All night?” The very suggestion sent me hurrying out of the room and nearly colliding with Stella, on her way back to the parlor with the baby. We both stopped short, yet the slight jarring the baby received didn't disturb him in the least. His eyes remained closed, his lips working as if still sucking on the bottle.

“Are you all right, Miss Emma? You're as white as a sheet.”

I waved away Stella's concerns while my own burgeoned. “I'm fine, but I'm going to call Dr. Kennison again. What in the world can be keeping him so long?”

But I'd no sooner reached the alcove and lifted the ear trumpet when a knock sounded at the front door.

Â

“He's fine, Emma. Lungs are clear, his heart's strong. Has a good grip, too. I'd say this is one healthy little fellow.” Dr. Kennison folded his stethoscope and slipped it into the medical bag at his elbow, the black leather worn and cracked from years of steady use.

I sighed with relief as I leaned over the kitchen table and rewrapped the swaddling blankets snug around the baby's pink body, which had only begun to grow plump in the way babies did at several weeks old. Our young man had awakened briefly during his examination, whereupon he surveyed the doctor with a puzzled frown, squeezed the offered finger, blew a bubble between his lips, and drifted back to sleep.

Poor thing. How long had he cried before I finally found him this morning? “You don't see any signs of exposure, then, Doctor?”

“Emma, relax. Even if he had been outside all night, which I very much doubt, don't forget it's summertime. The air wouldn't have done him a lick of harm.”

A few minutes later I walked him to the door. “So for now you'll keep mum about this, Doctor? I'd like a chance to discover who he is and why he was left here before too many people learn of his existence.”

“If you think that's best. Now, mind you mix his formula exactly according to the directions. I can't tell you how many undernourished infants I see whose mothers added too much water, trying to stretch their supply.”

“We'd never do any such a thing.” The very notion appalled me and I instinctively hugged the baby closer. “We'll take the very best care of him.”

He reached out a finger to stroke the baby's head. “I'm sure you will. If you need me, telephone. Otherwise I'd like to see him again in about a week. Say, Thursday?”

Beyond him through the open door a cloud of dust formed at the end of my driveway, and seconds later a police buggy came into view. “That's Jesse. Someone must have told him I called the station. Well, good-bye, Doctor, and thank you.”

The two men exchanged greetings before Jesse made his way to my front door. “Morning, Emma.”

“Good morning, Jesse. Did they tell you I telephoned, or can you read my mind now?”

As with Gayla, I'd known Jesse all of my life. We both hailed from the Point, the colonial, harborside section of Newport that had changed little in the past century. Though he was some ten years older than me, we'd forged a friendship based on our common origins and, more recently, through our mutual efforts to solve crimes and see justice done. Jesse hadn't necessarily approved of my involvement in local criminal matters, but neither had he turned down the vital information I'd been able to offer him.

Other books

Breathless Awakening (The Breathless Series) by Aybara, K

Lacy (The Doves of Primrose) by Kedrick, Krista

Following Christopher Creed by Carol Plum-Ucci

Stone Dragon (The First Realm) by Testamark, Klay

Stay by Mulholland, S.

Sisters of Shiloh by Kathy Hepinstall

Clochemerle by Gabriel Chevallier

La llamada de Cthulhu by H.P. Lovecraft

Sacrifice by Luxie Ryder

Number the Stars by Lois Lowry