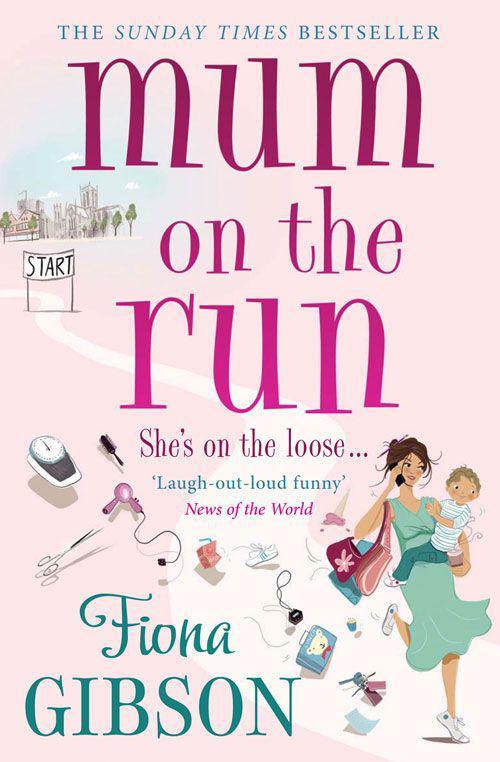

Mum on the Run

Authors: Fiona Gibson

FIONA GIBSON

Mum On The Run

For dearest Jen and Kath for all the laughs

Contents

‘Thank you, everyone, for coming along to our Spring into Fitness sports day. Now, to round off our afternoon, it’s the race we’ve all been waiting for

. . .’

No it’s not. It’s the race that makes me consider feigning illness or death.

‘. . . It’s the mums’ race!’ exclaims Miss Marshall, my children’s head teacher. She scans the gaggle of parents loitering on the fringes of the football pitch.

‘Go on, Mum!’ Grace hisses, giving me a shove.

I smile vaguely while trying to formulate a speedy excuse. ‘Not today, hon. I, um . . . don’t feel too well actually.’

‘What’s wrong with you?’

‘I . . . I think I’ve done something to my . . . ligament.’

Grace scowls, flicking back a spiral of toffee-coloured hair that’s escaped from her ponytail. ‘What’s a ligament?’

‘It’s, er . . .’ My mind empties of all logical thought. This happens when I’m under stress, like when a client blanches after I’ve cut in layers – even though she’s asked for layers – and insists that what she

really

had in mind for her ginger puffball was ‘something, y’know, long and flowing, kinda Cheryl Cole-ish . . .’

‘It’s in your leg,’ I tell Grace firmly.

‘What happened to it?’ Her dark brown eyes narrow with suspicion.

‘I . . . I don’t know, hon, but it’s felt weird all day. I must have pulled it or stretched it or something.’

She sighs deeply. At seven years old, rangy and tall for her age, Grace is sporting a mud-splattered polo shirt festooned with rosettes from winning the relay, the three-legged race

and

the egg-and-spoon. I’m wearing ancient jeans and a loose, previously black top which has faded to a chalky grey. Comfy clothing to conceal the horrors beneath.

‘Come on, all you brave ladies!’ cries Miss Marshall, clapping her hands together. Here they go: Sally Miggins, casting a rueful grin as she canters lightly towards the starting line. Pippa Fletch, who happens to be wearing – like most of the mums, I now realise – clothes which would certainly pass as everyday attire (T-shirts, trackie bottoms) but are suspiciously easy to run in. No one would show up at

Spring into Fitness

in serious running gear. That would be far too obvious. The aim is to look like you hadn’t even

realised

there’d be a mums’ race when you’ve been secretly training for months.

‘Come on, Laura,’ Beth cajoles, tugging my arm. ‘It’ll be fun.’

‘No it won’t,’ I reply with a dry laugh. Beth, the first friend I made on the mum circuit around here, is athletic and startlingly pretty, even with hair casually pulled back and without a scrap of make-up. I was presentable too, back in the Iron Age, before I acquired a husband, three children and a worrying habit of hoovering up my children’s leftovers. Waste not, want not, I always say.

‘Oh, don’t be a spoilsport,’ Beth teases. ‘It’s only to the end of the field. It’ll all be over in about twenty seconds.’

‘Yeah, you

promised

, Mum,’ Grace declares.

‘I can’t, Grace. Even if I was feeling okay, which I’m not with this ligament thing, I’m wearing the wrong shoes for running.’

Beth glances down at my cork-soled wedges. ‘Good point,’ she sniggers. ‘I’ll let you off . . .

this

time. But next time you forget your kit I’ll be sending a note home.’

‘Yes, Miss,’ I snigger. Beth grins and strides off towards the starting line.

‘Take them off,’ Grace growls.

‘What? I can’t run in bare feet! I might step on something like broken glass or poo or . . .’

‘No you won’t. It’s just grass, Mum. Nice soft grass.’

‘Grace, please stop nagging . . .’

‘Amy’s mum’s taken her shoes off. Look.’ Grace points towards the cluster of super-fit mums, all laughing and limbering up as if this is something one might do for pleasure. Sure enough, Sophie Clarke has tossed aside her sandals and is performing professional-looking leg stretches on the damp turf.

‘Any more mums keen to join in?’ Miss Marshall calls out hopefully. A trim thirty-something, she exudes kindness and capability. She manages to look after 270 children, five days a week. I find it an almighty challenge to raise three. I am in awe of her.

‘Anyway, I didn’t promise,’ I add. ‘I said I

might

. . .’

‘You did! You said at breakfast.’

Hell, she’s right. She and Toby were bickering over the last Rice Krispies, despite the fact that our kitchen cupboard contains around thirty-two alternative cereal varieties. ‘If you stop arguing,’ I’d told her, ‘I’ll do the mums’ race today.’ She’d whooped and kissed me noisily on the cheek.

It’s okay

, I’d reassured myself on the way to school and nursery.

She’ll forget.

I’d forgotten that children never forget, unless it’s con nected to teeth cleaning. I know, too, that I’m a constant disappointment to her, making promises I can’t keep. Pathetic mother with her colossal bra, non-matching knickers and carrying far too many souvenirs of her last pregnancy (stretch marks, wobbly tum), especially considering the fact that Toby is now four years old.

Across the field, Finn, my eldest, is sitting on a plastic chair between his best friends Calum and James. He, like Grace, is of athletic build: lanky with well-defined arms from drumming, and strong legs from playing football in his dad’s junior team every Sunday. Toby too exhibits signs of sporting prowess. Only this morning he bowled my powder compact across the bathroom and into the loo where it landed with a splash. Shame there’s no medal for that.

And

he denied responsibility. Told me that Ted, his hygienically-challenged cuddly, had done it.

Finn glances at me, then at the clump of mums all eagerly poised at the starting line. While Grace is desperate for me to do this, I know he’s praying I won’t. I don’t want to aggravate things between us even further. At eleven years old, he has become sullen and distant these past few months, and seems desperate for puberty to kick off big-time. Yesterday, I heard him bragging to James in his room that he’d discovered a solitary hair on his testicles. Other recent acquisitions are a can of Lynx and a tube of supposedly ‘miracle’ spot cream.

‘Mummy,’ Grace barks into my ear, ‘

everyone’s

doing it except you.’

‘No they’re not,’ I retort. ‘Look at those two ladies over there.’ Hovering close to the fence is a woman who’s so hugely pregnant she could quite feasibly go into labour at any moment, and a lady of around 107 in a beige coat and transparent plastic rain hat. ‘They’re quite happy to watch,’ I add. ‘Not everyone’s madly competitive, Grace.’

Her eyes cloud, and her lightly-freckled cheeks flush with annoyance. ‘Come on, Laura, shake a leg!’ trills latecomer Naomi Carrington. Naomi

is

wearing running gear. Tight, bubblegum-pink racing-back top, plus even tighter black Spandex shorts which hug her taut, shapely bottom like cling film, as if this were the sodding Commonwealth games. Her breasts jut out, firm and pointy like meringues, and she swigs from a bottle of sports drink. ‘I’m really unfit too,’ she adds. ‘Haven’t trained since last year’s Scarborough 10k. Mind you, I managed forty-nine minutes. That’s my PB . . .’

‘What’s a PB?’ I ask.

‘Personal best. Fastest-ever time.’ She throws me a ‘you are a moron’ look. ‘I know, not exactly a world record,’ she chuckles, ‘but pretty impressive for me. And I’m hoping to do even better this year.’

‘I’m sure you will,’ I growl, feeling my lifeblood seep out through the soles of my feet. If I ever attempted a 10k, the only way I’d cross the finishing line would be in a coffin.

She grins, showing large, flat white teeth which remind me of piano keys. Naomi is the proud owner of a perfect body, the whole town knows that – thanks to her stint as a life model for the Riverside Arts Society. Dazzling paintings of her luscious naked form were displayed in the Arts Centre café for what felt like a hundred years.

Perhaps I

should

run the race. I’ve felt spongy and wobbly for so long, maybe this is my chance to snap into action and do something about it. It could be the start of a new, sleek me, who wears racing-back tops and talks about PBs. I breathe deeply, trying to muster some courage, the way I imagine elite athletes do before world-class events. Across the pitch, Finn is poking the damp ground with the toe of his trainer. I know he’s wishing his dad were here. Jed would have entered the dads’ race and won it. He, too, would have been sporting a red rosette by now. But Jed isn’t here. He’s a senior teacher at another primary school – one far rougher than this – whereas I work part-time as a lowly hairdresser and can always take time off for school-related events. Lucky me.

Naomi is stretching from side to side, which causes her top to ride up (not accidentally, I suspect), exposing her tiny, nipped-in waist. Grace is chewing a strand of long, caramel-coloured hair, perhaps wishing she had a different mum – a properly functioning one with meringue breasts, like Naomi.

I swallow hard. ‘You really want me to do this, sweetheart?’

She looks up, dark brown eyes wide. ‘Yeah.’

‘Okay. Promise you won’t laugh?’

She nods gravely. Something clicks in me then, propelling me towards the starting line, despite my wrong shoes and bogus sprained ligament and the fact that Finn will be mortified. ‘Mum’s doing the race!’ Grace yelps. ‘Go, Mum!’ I daren’t look at Finn.

‘Well done, Mrs Swan,’ Miss Marshall says warmly. I bare my teeth at her.

‘Good for you,’ Beth says, giving my arm a reassuring squeeze.

‘You know I can’t run,’ I whisper. ‘This’ll be a disaster.’

‘It’s just for fun,’ she insists. ‘No one cares about winning.’ I muster a feeble smile, as if a doctor were about to plunge a wide-bore syringe into my bottom.

‘Your shoes, Mrs Swan,’ Miss Marshall hisses. ‘You might like to . . .’

‘Oh, God, yes.’ I peel off the lovely turquoise suede sandals which I bought in a flurry of excitement when my sister Kate came to stay. She chose snug-fitting skinny jeans; I headed for footwear because trying on shoes doesn’t involve changing room mirrors or discovering that you can’t do up a zip. As I scan the row of women, all raring to go, I realise I’m the fattest mum in the race. What if my heart gives out and I’m carted off on a stretcher? Beth grins and winks at me. Naomi, who’s set her sports drink on the ground behind her, assumes an authentic starting position like Zola-bloody-Budd. I ignore her and focus ahead. The pitch doesn’t usually look this big. Now the finishing line seems so distant it might as well be in Sweden. ‘On your marks, get set . . .

go

!’ Miss Marshall roars.

Christ, don’t they give you a warning, like some kind of amber alert? These aren’t women but

gazelles

, charging off in a blur of limbs and kicking up mud behind them. I’m running too. At least I’m slapping down each bare foot alternately and trying to propel myself with my arms like I saw Paula Radcliffe doing on TV.

The pack zooms ahead. Are they on steroids or what? They must have taken some kind of drug. If I survive this I’m insisting on tests. Right now, though, a sharp pain is spearing my side, making my breath come in agonising gasps. ‘Go for it, Laura!’ cries one of the dads, in the way that people cheer on the unfortunate child in the sack race who’s staggering behind, swathed in hessian, and finally makes it to the finishing line streaming with tears and snot after everyone else has gone home.

There’s cheering, and I glimpse Naomi punching the air in triumph at the finishing line. My bra straps have slipped down, and my boobs are boinging obscenely as I thunder onwards. I glance down to assess their bounceage, and when I look up something’s terribly wrong, because Jed is standing there. Jed, who should be at his own school, not witnessing the ritual humiliation of his wife. Worse still, he’s standing next to Celeste, that new teacher with whom he’s clearly besotted, although he acts all blasé (

overly

-blasé, I’d say) whenever her name pops up. Gorgeous, honey-skinned Celeste who, to top it all, is half-sodding-French.

I keep running, telling myself that they can’t be here, laughing and standing all jammed up together. It’s just some terrible vision caused by over-exerting myself. And they say exercise is good for you. No one mentions the fact that your chest feels as if it could burst open and you start hallucinating.

I glance back to check. Celeste is gazing up at Jed and fiddling with a strand of her hair. Anyone would think she’s his cute, doe-eyed girlfriend in her polka-dot skirt and sweet lemon cardi. She reaches out to pick something – a stray thread, perhaps – off Jed’s top.

Grooming

him, like a mating monkey. It’s sickeningly intimate. He smiles tenderly at her. Whenever I try to pick something off him, he bats me away as if I’m a wasp.

I charge on like a heifer, boiling with rage, my boobs lolloping agonisingly as I try to recall the last time Jed smiled adoringly at me. I can’t remember. It’s so horrifying to see him looking at her that way that for an instant I forget where I am. I lose my footing, skid on the muddied pitch and lurch forwards with arms outstretched, belly-flopping onto the ground with a splatter.

Dear God, kill me now.

I lie still, waiting for my life to flash before me. A lump of dirt, or possibly a live bug, has worked its way up my nose. With my eyes squeezed tightly shut, I’m poised to transcend to some heavenly Celeste-free zone, where no one is ever forced to take part in a mums’ race.