Mrs Midnight and Other Stories (24 page)

Read Mrs Midnight and Other Stories Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

By the middle of the second act Asmatov was a baffled man, uncertain whether he was witnessing a farce or a tragedy, or something that was quite horribly neither. The scene was laid in the house of assignation where one of the male clients has just died. The police appear, and an undertaker with a coffin. A horribly real corpse appears on stage, white and bloated in a bloodstained night-shirt and proves to be too large for the coffin. A bigger coffin is ordered. One of the bankers hides in the coffin and is assumed to be dead by his wife who shoots the undertaker and kills him. The corpse is manhandled in and out of coffins and hidden under tables and in cupboards. The other wife attempts suicide. By the time the curtain fell, half the audience were weak with laughter, the other half in a state of shock.

The curtain for the third act went up on Monsieur Fadinard’s bourgeois home again, but it was a scene of desolation. Coffins and corpses were being delivered to it, for no apparent reason, and the place was beginning to look like a charnel house. By the end of the act most of the main characters were dead, either killed by some bizarre accident or by each other.

The plot had become impossibly confused, but the last moments of the play, though barely comprehensible, were extremely memorable. Asmatov regularly dreamed about them for the rest of his life.

The last coffin to be brought onto the stage was accompanied by a weeping Madame Fadinard dressed in black, escorted by two policemen who had, by this time, arrested her for murder. The coffin, somewhat less than half size, was set up on an almost vertical stand facing the audience. It was then opened to reveal what looked like the corpse of the child Francine, pale and still as the night, clothed in an elaborate white lace gown. Asmatov could not tell if it was a wax doll of some kind being used, or the dwarf actress. He heard and almost felt a shudder pass across the audience.

The little coffin was covered with a red cloth. There came a tremolo from the fiddles in the pit and the shape beneath the cloth began to grow. A monkey bounded onto the stage and tore away the cloth to reveal a full sized coffin in its place. Long strands of white hair were sprouting from under the lid of the box. For several bars of music—a military march of some kind—the hair appeared to grow and long white tresses crawled across the carpeted stage towards the orchestra pit. There was a flash, a drum roll from the pit, the monkey leapt onto the coffin, tore open the lid and revealed the corpse of the General, grandfather to the young Francine, in his military uniform with the long white hair and whiskers that had poured out of the coffin. As the curtain slowly fell the coffin was picked up by six dwarfs dressed as guardsman and carried off stage to the strains of a solemn funeral march. There was a mutter of applause and laughter, then silence. When the curtain rose again the scene was empty of all coffins and persons. There remained only the corpse of the little girl Francine lying on the floor, dead, her doll beside her in its coffin. When the curtain fell again Asmatov wondered if there was going to be a riot. There was some applause, even the occasional ‘Bravo!’, but there were also shouts of protest, catcalls and boos. Asmatov himself felt exhausted; his expectations and feelings had been so remorselessly violated and confounded.

During the curtain calls that followed the hubbub died down, but there was not much clapping. The audience left the theatre in silence. Asmatov did not stay to see them out. He left by a side door and walked about the city.

He did not go into the theatre the following day. He stayed in his apartment and would not answer calls. He had felt strangely humiliated by the theatrical experience he had undergone because it had been so utterly beyond his comprehension. Besides, there was nothing he could do. The theatre was booked up for the next two nights; he must simply let events take their course.

He would rely upon Madame Asmatova, a plump amiable body whom everyone liked, to report back to him on the reaction of the town. She went out quite early that morning and returned at noon to inform him that the town was agog with last night’s events. Many people of course had not yet seen the show and some said that they would suspend judgement until they had witnessed it for themselves. Most people, however, regardless of whether they had seen

The Philosophy of the Damned

or not, had made up their mind about it.

A select minority declared that they had enjoyed a profound theatrical experience. Others, more sceptical of its artistic merits, remarked in a superior kind of way that, whether one liked it or not, the work they had seen was undoubtedly a sign of the times. It was noticeable that these people were a little reluctant to specify what that sign signified, and perhaps they were wise not to do so. The majority of those who had seen

The Philosophy of the Damned

or who had merely heard about it from those who had, decided that the play was depraved from beginning to end, some kind of obscene joke, and an insult to the people of Petropol.

This feeling grew after the second night and on the third day, following the final performance, Asmatov himself ventured out to hear what the audience had felt. It was a bitter cold night as Asmatov walked from café to café, from street corner to street corner, his face muffled against recognition, listening to what was being said.

The Philosophy of the Damned

was on everyone’s lips and the news was not good. Asmatov suspected a riot, or at the very least a vehement protest against Count Belphagore and his Apocalyptic Comedians. It was time for him to go to the theatre and see what was to be done.

Asmatov entered by the stage door to find all apparently deserted. The dressing rooms were empty and looked as though they had never been used. The stage was likewise swept and bare. Everything—scenery, props, costumes—had been cleared away with remarkable thoroughness. It was odd therefore that the trap door in the centre of the stage had been left open. Asmatov approached the hole and peered in.

The light was very dim and at first he could see little beneath him, but he could hear a low murmuring and rustling sound coming from below, as of many voices and bodies in subdued but agitated restlessness. A rank smell, half-human, half-animal emanated from the trap. Quietly, Asmatov let himself down into the space beneath the stage.

It was an extensive area, deep enough for a man to walk in comfortably, but full of stage machinery and equipment and lit only by a few oil lamps suspended from the wooden uprights which supported the stage above it.

As his eyes became accustomed to the dark, Asmatov saw that the whole of this area was crowded with vast crates or containers, most of them covered by cloths and tarpaulins. From within these containers came the sounds that he had heard. The noises troubled him because he could not quite fix in his mind whether they were human or animal. They were both; they were neither. He caught the odd articulate word, but even these were strangely enunciated, as if by a parrot or some other beast who barely understood their meaning. And yet in the depths of his being he grasped the burden of all these sounds, a burden of ceaseless gnawing agitation, the movement of creatures caught in a trap, who know they are caught and yet cannot stop struggling because that is all the life they have to offer.

With infinite reluctance Asmatov drew aside one of the cloths that covered the crates. What he saw amazed him. The crate was more like a wooden cage with the bars very close together but through them he could see that these vessels were packed tight with living beings. There were men, women, children, dwarfs, animals of all kinds, even birds and snakes and they shifted endlessly within their confines, uttering strange semi-articulate cries and grunts. Asmatov uncovered one crate after another, all packed with the same varied contents. None of the inmates of these wooden prisons took the slightest notice of Asmatov: all were intent on their ceaseless, futile inward movements, like sick sleepers who toss and turn, but never settle comfortably.

As Asmatov gazed upon this panoply of damnation, the words of Starets Afanasy came to him unbidden: ‘Keep thy mind in Hell and despair not.’ Just then he heard a sharp noise, a footstep; then he saw a light. A man carrying a bright gas lantern had entered the understage. It was Count Belphagore.

Asmatov saw him climb onto the crates and, bent double because of the lowness of the ceiling, walk across them, peering into their snarling depths. As the Count looked down at his suffering creatures, Asmatov could see his face brightly illumined by the lamp, his red hair and whiskers looking more than ever like the flames of a wind-blown bonfire. Belphagore’s expression was inscrutable; it seemed to Asmatov to be deeply, almost restfully absorbed in the contemplation of his brood. Once he pushed something down through the bars of one of his prisons and was rewarded by an orgy of groans and howls. At that moment the Count’s face lit up with ecstatic delight. Asmatov recoiled in horror, making a slight noise as he did so. The noise immediately alerted the Count. He looked up, at once fiercely watchful, like a fox who has just scented a rabbit.

Asmatov ducked down behind the crates, as above him he heard the Count leaping from one to the other, searching for him. Belphagore was muttering words in a strange tongue, not Italian, a guttural language that rumbled in the throat. Such a language, thought Asmatov, might be spoken by wild beasts one to another, could they speak. He knew now that the Count was intent on hunting him down.

Asmatov was stout, ungainly, fearful and already out of breath, but he had one slender advantage over the Count: he knew the theatre as well as he knew his own home. While Asmatov wove his way carefully around the crates he could hear, and even feel the Count leaping about above him, growling and occasionally sniffing the air. There was a little side door which opened into the orchestra pit from the understage, and it was towards this that Asmatov was tentatively crawling, trying hard to suppress his gasps for breath in the fetid air. Then he knew that the Count had sensed his direction. This was no time for caution. Asmatov made a leap for the little door and got through it with the Count hard on his heels.

Asmatov was surprised to find the orchestra pit cluttered with abandoned musical instruments. It took him only a moment to realise that he could put this to his own advantage. As the Count burst through the door to the pit, Asmatov seized a cello by the neck and advanced on him, driving the spike at its base directly against Count Belphagore’s chest. The Count gave a hoarse roar as he felt himself penetrated by the spike. Meanwhile Asmatov had leapt onto the conductor’s podium, seized the brass rail that separated him from the auditorium and, at the second attempt, had vaulted over it. As he ran up the central aisle of the auditorium he had just enough sense to realise that it might be wise to get out of the theatre by a side exit. Somewhere behind him the Count was roaring and thundering after him, but further and further away now.

Asmatov slipped out of the theatre by a pass door at the side and into an alley. Snow was falling, a rare event for Petropol, even in November, softening the streets, robing the town in purity. Asmatov put his coat collar up and hurried along in the direction of St Basil’s Square. As he approached it he began to hear the sound of a crowd murmuring. Then he was out of the narrow alley and into St Basil’s.

A large number of Petropolitans, some carrying torches, others with pickaxes and other crude offensive weapons were gathered on the steps of the Opera House. Around them snow was falling gently from a black sky. Asmatov kept his distance from them as he skirted the square, but he could see that one man was addressing them from the glass panelled portals of the theatre itself.

Behind the glass all had been blackness; then there was a flash of light, and Asmatov saw that Count Belphagore had entered the foyer. He was holding his gas lamp aloft, but unsteadily, and, as the light swung, the man’s red hair flamed in the blackness. He staggered like a drunkard, his eyes were wild; he looked like a madman. When they saw this the crowd became frantic. They rushed for the doors of the theatre and started to smash their way in.

Asmatov saw no more. He was making for his apartment on the other side of St Basil’s Square. He had a wife and child to think of.

***

Very early the following morning Asmatov with his wife and daughter made their way unobtrusively to the harbour and boarded the little steamer for Constantinople. A few days later the Red Army swept into Petropol. It would be idle, as well as a cliché, to say that the rest was history, because it always is, but the history of Petropol was one that Mr Asmatov, a man who knew his capacities and limitations, chose never to read. He was attending to his own history.

By the year 1923 Asmatov with his wife and daughter had found their way to England, and he had become the Front of House Manager of the Bijou Theatre in Godalming. It was a modest modern building which boasted, for the greater part of the year, a permanent repertory company offering the good citizens of Godalming a pleasant diet of comedies, farces and thrillers. Every week there was a new play which was, at the same time, always exactly the same. Asmatov’s daughter, Elena, had embarked on a moderately successful career as an actress and his plump wife had reconciled herself quite comfortably to the tea and small talk of an English Provincial Town. As for Asmatov, he looked back to the days of the Imperial Opera House, Petropol as another age. If he thought of Count Belphagore and his Apocalyptic Comedians, he could believe in them only as a kind of dream he had once had. But, as Mr Asmatov, who was a wise as well as a modest man, occasionally reflected, it is often in dreams that reality begins.

THE MORTLAKE MANUSCRIPT

I

What is it about dealers in rare books and manuscripts? One would have to go a long way to meet one who was

not

a little strange, and Enoch Stapleton was no exception to the rule.

When I first met him he must have been in his late thirties, though there was something ageless about him. He was a pale skinned man with very light blonde hair, and, though not technically an albino, he gave that impression. I was reminded of some exotic plant that has been left to grow too long in darkness, not exactly fat, but somehow flabby. Etiolated, I believe, is the technical term. At whatever time of the day or night that you visited him at his flat, he would always open the door to you in slippers and a pair of old fashioned pale blue and white striped pyjamas. He was, of course, unmarried and had, as far as I knew, no ‘partner’ of any description. His sexual orientation was a mystery to all those who knew him, and possibly to himself as well.

He took a lot of cultivating, but once he had decided that you were not a ‘yahoo’—the term he used for anyone beyond his particular pale—he could be extraordinarily helpful. His knowledge of the book and manuscript world was vast, and he had a great talent for persuading the possessors of valuable collections to disgorge their riches for sale or examination. Some normally reclusive and eccentric people can be extraordinarily charming when they want to be: Enoch was one such.

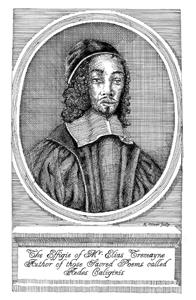

An Oxford colleague, Professor Stalker, had put me on to him when I began my researches for a book about the poet Elias Tremayne (1611-1660), the so-called ‘Black Metaphysical’. I had chosen Tremayne, partly, I admit, because no-one else had ‘done’ him recently—academics have to take these sordid factors into consideration nowadays—but also because I genuinely admired his work. There are moments in his only published book of verse

Aedes Caliginis

(‘The Temple of Darkness’, 1659) when he equals Donne, Crashaw and Vaughan, even at times touching the sublime heights of the great George Herbert himself. His cast of mind, however, was melancholy in the extreme, even by the standards of his time, hence, one presumes, his sobriquet. There is a touch of scepticism, even nihilism about his writing which seems rather modern. Take the opening stanza of perhaps his most famous poem ‘Life Eternall’.

When I doe contemplate Eternitie

It seems to mee a ring of endlesse Night

Not rounded with Delight

But circled with dark palls of coffined Death

Wherein no soule may draw sweet breath,

Save by the mercie of obscure Divinitie.

Notwithstanding his rather unconventional philosophical views, Tremayne was an ordained clergyman in the Church of England and for the whole of his relatively short adult life was vicar of the parish of Mortlake in Surrey where the Elizabethan magician Dr Dee had lived and died less than half a century earlier. Other than these meagre facts, little was known about him, or so I thought.

Tremayne’s reputation had always been comparatively obscure, but there had been moments when he emerged from the shadows. He was greatly admired by some of the 1890s poets, in particular Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symons. Baudelaire professed to be an enthusiast, and I was told that he is mentioned somewhere in one of Meyrink’s books. Tremayne’s small circle of devotees had been diverse and select.

I decided that even if I could not find out anything new about the man himself, I could at least explore his legacy and influence, which was where Enoch Stapleton came in. He was a renowned expert on the writers of the 1890s. If anyone could point me to the sources of Tremayne’s influence on the decadents, he could.

So I spoke to Enoch several times on the phone. He had e-mail, but only used it on sufferance and regarded today’s twitterers and bloggers of cyberspace as ‘yahoos’. Finally, after an exchange of letters, I was allowed to pay him a visit at his flat which was the top floor of a very undistinguished semi-detached villa in Cricklewood. After getting over the initial shock of the pyjamas, I had somehow expected his apartment to be squalid and chaotic. On the contrary: though all the rooms I saw were crammed with filing cabinets and bookshelves; everything in them was spotless and orderly. What pictures he possessed were monochrome engravings or etchings. The walls were painted a neutral mushroom-coloured hue, the only real colour on show deriving from the rich bindings or bright dust-jackets of some of the books. The impression given off was ascetic and obsessive. This last quality was underlined when I expressed a desire to relieve myself and he showed me to what he called ‘the guest lavatory’.

We sat at a table by the window on hard chairs, each with a cup of weak, milky tea—the only beverage he ever offered—and discussed Tremayne. I discovered that he knew a great deal more about the man than I did, which made me feel rather fraudulent. However, I told myself, I was a scholar, an Oxford don no less, while Enoch was a mere antiquarian, which meant that his knowledge, though extensive, lacked system and discipline. It was a distinction which comforted me at the time, less so now.

I asked about Tremayne’s connection with the 1890s men.

‘Of course,’ said Enoch, ‘you know Tremayne was an occultist.’

I nodded glumly. I had guessed as much from some of the obscurer images in his poems, and had rather hoped this was to be

my

discovery. But apparently it was known already.

‘His poem “The Tree”. You know it, of course.’

I nodded. It was Tremayne at his most knotty and metaphysical and I could make very little of it.

‘It’s almost impossible to make head or tail of it until you realise that the ten verses correspond to the ten Sephiroth of the Cabbala. Tremayne is trying to equate them with the wounds of the crucified Christ. Take the first verse:

An earthlie wounde, eternall diadem,

Pointes of the thorne, one pointe in Paradise.

Those rubie drops transmute to many a gem

Upon the crowne wherein the Deathless dies,

Th’ Unmanifest yet shines for mortall eyes.

‘Not Tremayne at his best, I grant you, but it begins to make sense when you realise that he is equating the Crown of Thorns with Kether, the Crown, the supreme sphere or “path” on the Sephirotic Tree. And of course there is another general equation with the “tree” of the cross. There’s a woodcut from a Syriac New Testament printed in 1555 which does much the same thing. You’ll find it reproduced in Gareth Knight.’

He darted to a bookcase, pulled out a volume with a rather anaemic dust jacket and showed me. I was convinced.

‘Then of course, there’s the stuff about him in Aubrey. You know about that, I suppose?’

I was beginning to be irritated: not so much by Enoch’s omniscience, as by his mistaken assumption of mine. But he anticipated my thoughts.

‘You may not. The material was discovered muddled up with some of Anthony à Wood’s papers at the Ashmolean by Oliver Lawson Dick shortly before he committed suicide, and he intended to add it to his standard edition of Aubrey’s

Brief Lives

. Unfortunately he died before he could. I only know about it because some of Dick’s papers passed through my hands at one point, but I believe it has been published in a journal somewhere. I’ll look it out for you. As usual Dick has edited it down very efficiently from scraps written by Aubrey at different times and on different pieces of paper. No wonder Anthony à Wood called Aubrey “magotie-headed”.’ Enoch went to a filing cabinet and, after a brief search, fished out a single sheet of photocopied typescript.

‘Here we are. You can keep that. I have another copy.’

I read:

ELIAS TREMAYNE

Naturall s. of Sir Thos. Tremayne of Pengarrow in Cornwall. He was a man of melancholique humour and black complexion, but of a very good witt. His mother thought by some to have been a Blackamore whom Th. Tremayne brought home from his voyages. At Oxford (Univ. Coll.) shewed himself most ingeniose and took holy orders. Found favour with W. Laud A. B. Cant [William Laud, Charles 1st’s Archbishop of Canterbury] and appointed to the living of Mortlack, but thereafter, though much in hopes of preferment, was disappointed,

causa ignota

[for an unknown reason].

Scripsit:

Aedes Caliginis

(Oxford 1659) sacred poems, but some so darke and tainted with esoterique doctrine, they invited much cencsure. Moreover, he had been of the King’s party in the late Civill Warres. Mr Ashmole did shew me once a treatise of Mr Tremayne’s in M.S.,

De Rerum Umbris

[Concerning the Shadows of Things] which he did not lett me read. Later he told me he had destroyed the M.S. which he sayd he was loath to do, but he greatly feared lest it fall into the hands of giddy-heads and those who foolishly dabble in

quod latendum

[what should remain hidden].

Old Goodwife Faldo (a Natif of Mortlack) told me that Mr Tremayne did often aske her histories of Dr Dee whom she had known when he did live in that place. It was rumoured that Mr Tremayne had an M.S off an old servant of Dr Dee’s house which this person had kept (or purloyned) from the same, and that the sayd M.S. contained a relation of a magicall encounter not to be found in Mr Ashmole’s collection. Moreover it showed by many Alchymicall signes and formularies how certain wonderfull giftes may be obtained through intercourse with angells and daemons. (She sayd.) When I asked if this M.S. was extant still, Goodwife Faldo replyed that she knew not, but that certain persons in Mortlack tell how in the last year of Mr Tremayne’s life (anno 1660) a very tall black man did come and take away his papers, leaving Mr Tremayne much affrighted. Thereupon he fell into a great distresse of mind and dyed. But this mere whim-wham and idle gossip, no doubt.

Here at least was a scrap more information on the man’s life, and it was sufficiently unknown to count as a discovery. An academic with a reputation to burnish knows how to make bricks with very little straw.

‘I expect the “black man” who removed his papers was some Puritan busybody,’ I said. Enoch said nothing, but I could tell that he was irritated by my remark. There was a pause.

‘Those papers may not have disappeared altogether,’ he said. ‘There are clues to their subsequent history. Horace Walpole is said to have had some Dee material, and then there is an item in a catalogue of Bulwer Lytton’s manuscript collection which has never been properly identified. The catalogue entry reads something like: “Mortlake MSS. Occult writings in the autograph of Dr John Dee with additional comments by a later 17th c. hand.” Could that be Tremayne’s? Then in about 1900 A.E. Waite mentions something called “The Mortlake Manuscript” in a letter to his friend Arthur Machen. It is obviously of occult significance. He says something like “Perdurabo”—that was Crowley’s magical name in the Golden Dawn—“claims he has the Mortlake Manuscript and will make use of the keys”. I don’t know. These things could mean nothing, but a number of us have been on the lookout for the Mortlake Manuscript for some time now. We believe it could be out there.’

‘Who is “we”?’ I asked, rather expecting an evasive reply, which I duly received.

‘Just a figure of speech. Would you like me to keep you informed of progress? It might be useful to have an Oxford don to authenticate it.’

I merely nodded. This was no time to take offence at his condescension.

I kept in touch with Enoch Stapleton and he fed me scraps of information that he turned up about Tremayne. There was an essay on the Metaphysical Poets in which Arthur Symons praises Tremayne, and the unpublished preface to

The Angel of the West Window

by Gustav Meyrink which contains the following cryptic sentences:

It was the cleric Tremayne who best understood Dee until these present times. I have but once been afforded a brief glimpse of that elusive document

The Mortlake Manuscript

, but it was sufficient to convince me. Who among those of us who have seen it would not give all their worldly goods for a further study of such a priceless treasure?

‘Meyrink must have seen it when he became associated with The Golden Dawn,’ said Enoch. ‘Perhaps Crowley himself showed it to him, though there’s no record of them ever meeting. As you know, both Meyrink and Crowley were interested in Dee. Crowley actually believed he was the reincarnation of Dee’s medium and nemesis, Edward Kelley. That Meyrink reference from about 1930 is the last we hear of the Mortlake Manuscript. . . .’ Enoch stopped and looked at me intently. ‘You don’t seem very interested,’ he said.

‘No. I am. I am. I’m just not terribly into this occult stuff. It all seems to me such dreadful rubbish.’ I paused, suddenly realising that I might have caused offence. ‘Forgive me. I don’t mean to be rude.’