Mrs Dalloway

Authors: Virginia Woolf

PENGUIN BOOKS

Mrs. Dalloway

Virginia Woolf is now recognized as a major twentieth-century author, a great novelist and essayist and a key figure in literary history as a feminist and a modernist. Born in 1882, she was the daughter of the editor and critic Leslie Stephen, and suffered a traumatic adolescence after the deaths of her mother, in 1895, and her step-sister Stella, in 1897, leaving her subject to breakdowns for the rest of her life. Her father died in 1904 and two years later her favourite brother Thoby died suddenly of typhoid. With her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, she was drawn into the company of writers and artists such as Lytton Strachey and Roger Fry, later known as the Bloomsbury Group. Among them she met Leonard Woolf, whom she married in 1912, and together they founded the Hogarth Press in 1917, which was to publish the work of T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster and Katherine Mansfield as well as the earliest translations of Freud. Woolf lived an energetic life among friends and family, reviewing and writing, and dividing her time between London and the Sussex Downs. In 1941, fearing another attack of mental illness, she drowned herself.

Her first novel,

The Voyage Out

, appeared in 1915, and she then worked through the transitional

Night and Day

(1919) to the highly experimental and impressionistic

Jacob's Room

(1922). From then on her fiction became a series of brilliant and extraordinarily varied experiments, each one searching for a fresh way of presenting the relationship between individual lives and the forces of society and history. She was particularly concerned with women's experience, not only in her novels but also in her essays and her two books of feminist polemic,

A Room of One's Own

(1929) and

Three Guineas

(1938). Her major novels include

Mrs. Dalloway

(1925),

To the Lighthouse

(1927), the historical fantasy

Orlando

(1928), written for Vita Sackville-West, the extraordinarily poetic vision of

The Waves

(1931), the family saga of

The Years

(1937), and

Between the Acts

(1941). All these are published by Penguin, as are her

Diaries

, Volumes IâV, and selections from her essays and short stories and

Flush

(1933), a reconstruction of the life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning's spaniel.

Elaine Showalter is Professor of English at Princeton University, and the author of

A Literature of Their Own: Women Writers from Brontë to Lessing

(1977),

The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830â1980

(1985) and other books on women writers and feminist literary criticism. She has lectured widely in the United States and England on women's literature, psychiatric history and literary theory, and has edited

The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature and Theory

. Her most recent books are

Sexual Anarchy

(1990) and

Hystories

(1997).

Stella McNichol is the author of a critical study of

To the Lighthouse

(1971) and of

Virginia Woolf and the Poetry of Fiction

(1990), and the editor of a group of Virginia Woolf's stories,

Mrs Dalloway's Party

(1973).

Julia Briggs is General Editor for the works of Virginia Woolf in Penguin.

VIRGINIA WOOLF

WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES

BY ELAINE SHOWALTER

TEXT EDITED BY STELLA McNICHOL

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi â 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by the Hogarth Press 1925

This annotated edition published in Penguin Books 1992

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 2000

27

Introduction and notes copyright © Elaine Showalter, 1992

Other editorial matter © Stella McNichol, 1992

All rights reserved

The moral right of the editor has been asserted.

Printed in England by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Set in 10½/12½ pt Monophoto Garamond

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject

to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

EISBN: 978â0â141â90410â8

Diary

:

The Diary of Virginia Woolf

, 5 vols., ed. Anne Olivier Bell (Hogarth Press, 1977-84; Penguin Books, 1979â85)

Letters

:

The Letters of Virginia Woolf

, 6 vols., ed. Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautmann (Hogarth Press, 1975)

Essays

:

The Essays of Virginia Woolf

, 6 vols., ed. Andrew McNeillie (Hogarth Press, 1986â)

CE

:

Collected Essays

: 4 vols., ed. Leonard Woolf (Chatto & Windus, 1966, 1967)

In 1961, when I first read

Mrs. Dalloway

as a student at Bryn Mawr College, Virginia Woolf's place in twentieth-century fiction was still under-estimated and her feminist concerns were largely unrecognized. My lecture notes begin: âMarch 8: Virginia Woolf. More limited intellectually than James Joyce. Interested in the moment and in certain philosophic theories of time. In

Mrs. Dalloway

we are immediately confronted with Clarissa and must face haunting questions concerning her. Has she made the right decisions in life? Is she a support to her husband?' Clearly these ladylike questions were the ones our professor believed

should

haunt respectable young women thinking about their own decisions in life.

Woolf's literary standing has changed drastically over the past thirty years, but the character of Clarissa Dalloway remains puzzling.

1

As Margaret Drabble has pointed out, like her predecessors Jane Austen and George Eliot, Woolf âchose on the whole to describe women less gifted, intellectually less audacious, more conventional than herself.'

2

Indeed, in writing her fourth novel, at a moment that marked her own sense of artistic independence and maturity, Woolf chose as her heroine a London society lady whom even she thought âtoo glittering & tinsely.'

3

Woolf's contemporaries found Clarissa class-bound and slight.

Furthermore,

Mrs. Dalloway

demands our judgment of its heroine from the moment we encounter its eponymous

title. By her emphatic use of âMrs.', Woolf draws our attention to the way in which the central woman character is socially defined by her marriage and masked by her marital signature. Walking in London, Clarissa Parry Dalloway experiences âthe oddest sense of being herself invisible; unseen; unknown . . . this being Mrs. Dalloway; not even Clarissa any more; this being Mrs. Richard Dalloway' (p. 11). Woolf was well aware that, as feminist theory now puts it, âthe name of the husband is one of the strongest insignia of patriarchal power.'

4

Is Mrs. Dalloway a sad example of the way women have been rendered invisible by the state and the law; or is she perhaps rather a defiant figure who offers a critique of patriarchal power? Critics have strongly disagreed in the way they see Clarissa. At one extreme, the novelist Paul Bailey argues that âat her most interesting she is a snobbish, vain, repressed lesbian who has dabbled in culture, but for the greater part of the novel she is only a shadow, poetically enshrined.'

5

At the opposite extreme, the feminist critics Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar describe her as âa kind of queen' who âwith a divine grace . . . regenerates the post-war world.'

6

Yet a contemporary feminist reading which would substitute a liberated Ms. Dalloway for Woolf's ambiguous heroine, or would make Clarissa a priestess or goddess, seems to miss the point as well. Woolf's deliberately realistic title places

Mrs. Dalloway

in sharp contrast to James Joyce's mythically titled and structured

Ulysses

which she was reading when she began her own novel. Clarissa is not Penelope or Athena, but rather an ordinary woman on an ordinary day. Indeed, what is so moving and profound about the book is the way Woolf sees behind people's social masks to their deepest human

concerns, without elevating them to the level of myth. Virtually all the characters in the novel have failed to live up to their early dreams and ambitions. Clarissa fears that her life has been superficial and passionless. Richard Dalloway has not succeeded in politics as he had hoped. Peter Walsh, a Socialist and would-be writer, has not fulfilled any of his literary ambitions. The most rebellious character, the âwild, the daring, the romantic' Sally Seton has married a bald manufacturer from Manchester. The intellectual Doris Kilman has become an embittered religious fanatic. Septimus Smith, who had dreamed of being a poet, suffers from an inability to love. Yet the meaning of each life is larger, more diffuse, and less predictable than these simple statements will allow. Clarissa will not label people as successes or failures, or say âof any one in the world now that they were this or were that' (p. 8).

Like

Ulysses

,

Mrs. Dalloway

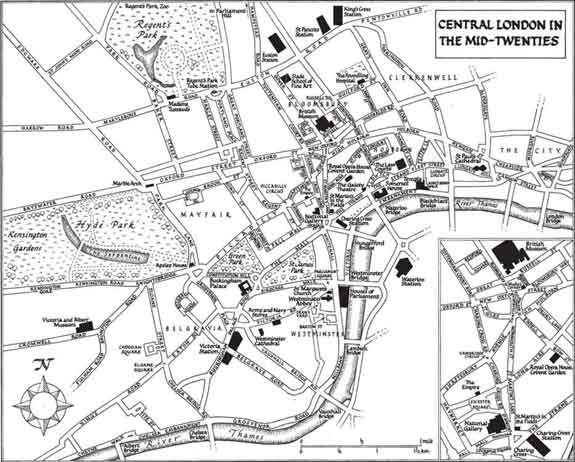

takes place on a single day, Wednesday, 13 June 1923.

7

It follows the heroine from early morning through to night of a London day on which she gives a large formal party. Although she has just turned fifty-two, Clarissa's mind keeps returning to the past, to another June day in 1889 when she was eighteen, and involved in an adolescent romance with Peter Walsh. She is obsessed with these memories, and with her decision not to marry him, in part because Walsh is due to return to London after a long absence in India, and in part because her own daughter Elizabeth is turning eighteen. Thus the female life cycle of sexual flowering and marital decision is about to repeat itself in another generation. At the beginning of the novel, Clarissa is convinced that the drama of her own life has

come to an end; âthe five acts of a play . . . were now over' (p. 51). As a woman who has come to the end of her childbearing years, Clarissa finds herself constantly aware of mortality and loss. But by the novel's end, she has come, if only fleetingly, to accept the loss of the âtriumphs of youth' and to face the next stage of her life.