Mr Briggs' Hat: The True Story of a Victorian Railway Murder (30 page)

Read Mr Briggs' Hat: The True Story of a Victorian Railway Murder Online

Authors: Kate Colquhoun

Tags: #True Crime, #General

A small piece of theatre remained.

Do your hats make it into the second-hand trade?

Parry asked Daniel Digance.

He took offence, replying frostily,

My trade is of a first-class not second-hand. I know nothing of the second-hand trade in hats.

Solemnly, Parry then began to hand a series of old hats one by one to the witness, telling him as he did so that each one had been bought in the second-hand markets. Peering at their linings, Digance was forced to confess that all of them bore the mark of his own shop in the Royal Exchange.

*

The prosecution’s case ended so abruptly that several of the spectators seemed unaware that the defence had begun until they

noticed a change in the tone of Serjeant Parry’s delivery. The hectoring of his cross-examination had modulated to a low and almost inaudible voice that had the effect of stilling the fidgeting public as they strained to catch his words. Apparently overwhelmed now that the array of evidence marshalled against him had finally been exhausted, Müller ceased to scribble feverish notes, dropped his head into his hands and stooped down behind the front of the dock until he had almost disappeared from sight. Half an hour later, when he recovered his nerve and lifted his head, Parry was still only halfway through his opening address.

The prosecution had failed to put Müller at the scene of the attack, or to identify a murder weapon, and Parry had performed well in his cross-examination of the hatter Daniel Digance, making him look both a snob and a fool. His routine with the hats had been carefully choreographed, proving beyond doubt that the one found in Müller’s possession might easily have been bought in the second-hand trade. Lodged in the jury’s minds was the testimony of several witnesses that the prisoner had hurt his foot some days before the attack on Thomas Briggs, eliminating conjecture that it was injured during the jump from the moving train.

On the other hand, Parry had been unable to undermine materially either Jonathan Matthews or Elizabeth Repsch’s statements about Müller’s ownership of the battered hat and he had missed an opportunity to emphasise that the hat might, just as convincingly, have belonged to Matthews. It all now rested on what new evidence he might submit for the defence. Would he be able to present an alternative scenario for the discovery of Briggs’ watch in Müller’s travelling trunk? Would he offer a convincing alibi? Might Thomas Lee’s statement about the two men allow Parry to insinuate into the case enough uncertainty to set his client free?

Parry began with a measured attack on the unscrupulousness of newspaper reports, reminding the jury that

what has been

written has been read probably by every one of you gentlemen – certainly by almost every person capable of reading a newspaper in the country.

Gentlemen

, he continued,

the crime of which this young man is charged is almost unparalleled in this country. It is a crime which strikes at the lives of millions. It is a crime which affects the life of every man who travels upon the great iron ways of this country. A thrill of horror ran through the whole land when the fact of this crime was first published. Gentlemen, this is a crime of a character to arouse in the human breast an almost instinctive spirit of vengeance. It is a crime which demands a victim.

Parry considered that the press had prejudiced the case

on a massive scale

. The jury, he warned, must exert every effort to make a passionless analysis of the evidence. The law must bypass vengeance and aim only for unqualified truth.

Parry knew that the prosecution’s case was founded on circumstantial evidence and suspicion and he was at pains to admonish the jury against conjecture. They must, he declaimed, be as satisfied of Müller’s guilt as surely as if their eyes had seen him do the deed. The evidence must be complete. It must be certain. Any doubt whatsoever rendered

the chain of evidence incomplete and the jury ought not, and cannot act upon it

.

He reminded them that he had tested the prosecution’s case, questioning the competence of witnesses, demanding facts over hypotheses and suggesting competing theories to demonstrate how much doubt lay at the heart of the case. Neither of the two hats, he asserted, could be positively identified as having belonged either to Müller or to Mr Briggs. That Müller had once owned a hat like the one found in the train was not proof that the broken hat belonged to him. The silk hat might easily have been purchased in the second-hand trade where it was customary to cut them down or alter their shape and where many were stuffed with tissue paper to make them fit. Further, it was not unlikely that Müller had bought Briggs’ chain and watch at the

docks. Knowing that they may have been attained illegally, it was natural for him to have denied the fact at the time of his arrest.

Parry professed disingenuous indignation at the suggestion that Jonathan Matthews was on trial or that he had been involved in the murder. But he alerted the jury to the fact that Matthews’ evidence was so unreliable that

no body of sensible men would for a moment pay any attention to it … He is evidently actuated by a desire to obtain the reward and that has animated his whole conduct. I should be very sorry to charge him with being a party to the murder, but I should be very wicked if I were not to say that suspicion is pointing to him.

He reminded them that Matthews was unable to corroborate his account of where he was on the night of the murder. Additionally, Matthews appeared to have tried to mislead them all with his story about leaving his hat at Down’s while admitting that he also had a hat

exactly like

the one now in court. Matthews’ hat had a similarly striped lining: what had become of it? Matthews, concluded Müller’s counsel,

tells an untruth both before the coroner and the magistrates and never corrects that untruth until now when he knows we have a witness to show that Mr Down went out of business … Is Mr Matthews trustworthy?

Parry accepted that a suspicion existed that the smashed hat belonged to Müller, but he warned the jury that suspicion was insufficient. Müller’s vain boastfulness around his friends and his varied stories were not proof of his guilt. Additionally, Hoffa saw him with money before the murderous Saturday. If he had not bought the watch and chain with it, then what did become of those pounds? Since none of the witnesses could agree about what Müller wore on Saturday or during the following week, Parry contended that the prosecution had not established that a pair of dark trousers was missing. Indeed, he reminded them, several witnesses had testified that Müller wore both the pairs of trousers he possessed after the 9th and that neither showed signs of blood or of having been cleaned. These facts and others,

cautioned Parry, were open to interpretation and, since a verdict of not proven was not allowed under English law, the jury’s only course was to find the prisoner not guilty.

The barrister went on to characterise Müller as a

mere stripling

of a lad whose many friends had testified to his

kind and trusting nature

. Was it possible that powerful, sober Mr Briggs had been overpowered and dragged across the compartment by this pale youth? Parry claimed that the prisoner maintained a calm containment that none of the police involved in the investigation, nor his gaolers, had ever seen slip. Openly expressing his intention of going to America some weeks before 9 July, Müller had taken passage in his own name and sent a letter confirming the name of his ship to the Blyths. Were these the actions of a criminal?

Thus far, it appeared to the spectators hanging on Parry’s words that the barrister would rely solely upon the weakness of the prosecution and the undisguised conduct of his client. Then, to the court’s evident satisfaction he announced that he would call the

unimpeachable gentleman

Thomas Lee to prove that when the train left Bow Station two men had shared Briggs’ compartment. Further, he would prove an alibi through the testimony of a lodging-house keeper and an omnibus conductor who would swear that Müller was elsewhere at the time of the murder – in Camberwell, exactly as he had told Hoffa he would be when he left the Repschs.

Had Parry been defending a less serious charge than murder he would have been allowed to

summarise the defence’s case

again at the end of the trial. But in murder trials, this was proscribed – unfairly in the view of many prominent legal minds, who felt the proceedings were thereby weighted in the Crown’s favour. Knowing, then, that this was his only opportunity to address the jury, Parry’s impressive, hour-long oratory drew towards its conclusion with a moving entreaty to find the evidence against his innocent client unsatisfactory. Relying on his experience of juries

acquitting rather than sending a man to his death, he advanced on the twelve men in the jury box and appealed to their religious sensibilities.

Gentlemen, if ever there was a case in which care and caution ought to be exercised by Christian men … it is a case like this, where the life or death of a fellow creature hangs upon the balance … You possess a transcendent power to bid that young man to live or to die.

It was five o’clock by the time Parry returned to his seat. The next day he would call a handful of new witnesses. Eager to conclude the trial and concerned that the jury would be left with insufficient time to agree their verdict before Sunday interrupted them, Judge Pollock ordered the court to reconvene an hour earlier than usual the following morning.

At seven minutes past five o’clock Müller was removed from the dock,

apparently exhausted and depressed

by Parry’s emotive entreaty. By dusk on Saturday it would all be over.

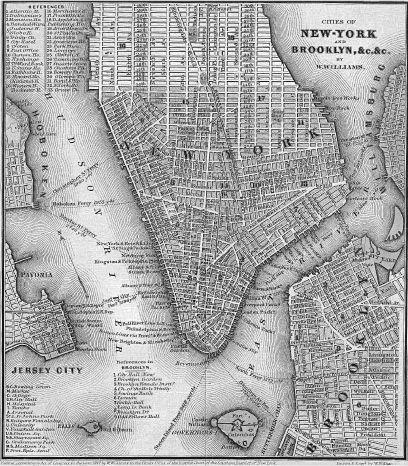

Map of New York, 1847. A warren of southern streets gave way to the twelve parallel avenues that stretched north to 44th Street.

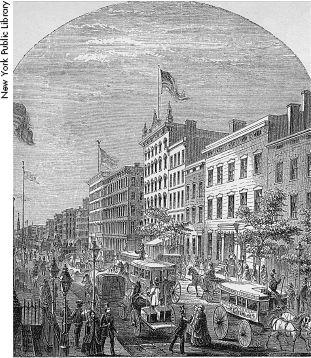

Broadway, 1862, bewilderingly alive with snapping reins and shying horses, fine shops, bright clothes, vagrant children and burly cops.

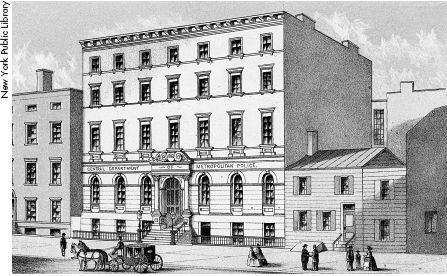

300 Mulberry Street, Manhattan, 1863. The New York Police Department’s headquarters.