Moonlight Murder on Lovers' Lane (4 page)

Read Moonlight Murder on Lovers' Lane Online

Authors: Katherine Ramsland

Several letters were printed verbatim, which helped to swell the reach of the local papers. Everyone wanted to see what this supposed man of God had written to his married mistress. The murders acquired a romantic patina akin to Romeo and Juliet.

Neither James Mills nor Frances Hall formally identified their deceased spouses. No autopsy was ordered and funerals were conducted for both victims. The bodies had decomposed too much for full embalming, so the undertakers recommended quick disposal. As Edward was displayed in his ecclesiastical vestments, more than 200 people showed up for the service.

Some members of the minister’s congregation still believed in his integrity, a fair amount of gawkers attended the service, too. When it concluded, Edward’s body went into the Stevens family vault in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

To the surprise of many church members, Frances Hall sent a wreath for Eleanor’s funeral, which took place the next day before a much smaller gathering. She was buried in Van Liew Cemetery on Georges Road in New Brunswick.

Jim Mills at wife’s grave

On Monday, the investigation was transferred to Joseph E. Stricker’s office in New Brunswick, because some officials believed that the couple had been killed over the county line. Although this matter was still undecided, Stricker accepted the challenge. It was the start of what would become a political tug o’ war.

To cover all bases, grand juries were convened in both counties. Despite the appearance of an orderly approach, chaos was rampant.

Even worse, people still flocked to the crime scene to take souvenirs, making it difficult for police to search the area carefully for the murder weapon or other items. People not only stripped the crabapple tree, but had also dismantled the abandoned Phillips farmhouse. As a crime scene, it was pretty much worthless.

However, the investigation now aimed at exposing secrets and lies.

Chapter 10: The Bodies, Again

Nearly two weeks went by without a break. Stricker struck out at every turn. Beekman publicly criticized him and stepped back in without anyone asking him to. Beekman decided that autopsies should have been performed on the deceased, so he wanted them exhumed for another look. In a fumbling effort to get information without having to commit to anything, the Middlesex County Board of Freeholders offered a $1000 reward, to be paid only if the information proved that it was a Middlesex County crime.

Distrustful of the police, Frances hired a former New York County assistant district attorney, Timothy N. Pfeiffer, to protect her rights and to look further into her husband’s death. He hired a private investigator, which added yet one more nose sniffing around.

Officials scheduled the exhumations, and disinterred Eleanor’s body first. A doctor from each of the two counties went jointly to work.

They could see that Eleanor had decomposed quickly. The physicians examined her three bullet wounds and examined the cut across her throat. It was deep, slicing down to the spinal cord. They realized that the killer had been carrying a very sharp knife.

Autopsy table

Photo by Jimmie Johnson

They found that the windpipe had been severed, along with the esophagus, as if to silence the soprano. Eleanor had also sustained scratches on her arms, below the elbows, and had a wound on her upper lip. Although this autopsy revealed a few more items, it was still not exhaustive, and Eleanor was reinterred with a shocking secret still preserved.

In the meantime, Charlotte Mills gave out stories that her mother had believed that Frances had once tried to poison her. To protect herself, Charlotte retained an attorney.

Detectives learned that Frances had sent clothes to be cleaned shortly after the murders, so they visited the cleaner. They discovered that she had asked for a coat to be dyed black. Was this to cover up stains, they wondered? Like bloodstains? The cleaner did not recall any stains. They confiscated the coat as evidence.

Politics delayed Edward’s autopsy, but finally it was performed. Investigators had decided that he had been killed first with a single bullet. Abrasions were found on his hands, particularly on the back of the right index finger and left little finger. There was a small bruise on the tip of the left ear and a perforating wound on his right calf, five inches below the kneecap. However, no information from this examination moved the case forward.

The investigators pondered ways to get closer to their suspects, but everyone seemed to be hiding behind an attorney. They thought it might be easy to get Willie to talk, because he was so excitable, but first they had to get through the front door of that imposing mansion.

Chapter 11: First Arrest

Frances was entertaining several friends when police cars pulled up, so she didn’t notice they were there. Willie answered the door and was ordered to get into the car. He was not allowed to tell his sister anything. The police delivered him to the Somerset County Court House for interrogation.

Sometime later, Frances noticed that Willie was missing. No one knew where he was. Distraught, she called police to report his disappearance. Police began to search, but then Willie came home and said he had been detained. Frances’ attorney, Timothy N. Pfeiffer, was enraged. He was adamant that such an unprofessional incident must never happen again.

On October 8, a Sunday, one of the many avenues for investigation suddenly became fruitful. Detective Frank Kirby brought in four people for questioning: Pearl Bahmer, Raymond Schneider, and two of Raymond’s friends, Clifford Hayes and Leon Kaufman. There was more to this couple, detectives believed, than their apparently innocent discovery of the crime scene.

A story formed from their separate accounts about Schneider meeting Kaufman and Hayes around 10:30 PM on the night of the murders, not far from De Russey’s Lane. Hayes had brought a gun. Pearl was also there, with a man he didn’t know, and they had disappeared together. Around 11 PM, Kaufman left Hayes and Schneider and went home.

From these bare facts, detectives reconstructed a scenario. They charged Clifford Hayes with the murders.

The press statement indicated that the Hall-Mills homicide had been the result of mistaken identity. Hayes had thought that Charlotte was Pearl and that Edward was her “other man.” Hayes thought she’d been cheating on his buddy, Schneider, so he’d killed them as punishment. Case closed. It had been an unfortunate instance of two innocent people at the wrong place and the wrong time.

Officers pose to demonstrate where bodies lay

However, few who read the papers bought this explanation. It failed to account for why Eleanor’s throat was cut, the lovers’ letters were torn and scattered, and the corpses were posed. It also seemed odd that, if Hayes had been close enough to pose them, he had not realized that he had shot and cut the throat of a stranger, not Pearl.

Hayes was mystified about the accusation.

“Why would I stick around New Brunswick,” he asked, “if I was the killer?” In addition, his brother gave him an alibi.

Soon someone leaked the story that police had relentlessly interrogated Schneider for over 30 hours before he implicated Hayes. He’d just wanted the interrogation to stop, so he made up a story that had won him some relief.

Beekman ignored these problems. To his mind, the mystery was solved.

But Stricker expressed doubts. He still suspected the victims’ families, certain they knew more than they were saying. Their behaviors suggested secrecy.

Then Pearl Bahmer’s father—Pearl’s “other man”—claimed that Schneider was the killer. Schneider denied the accusation, but admitted lying about Hayes, so Hayes was released. The case was fast going cold.

Chapter 12: Scandal for Sale

On October 16, two bloodstained handkerchiefs picked up at the Phillips farm were turned in to the police. One had no identifying marks, but the other was a smaller handkerchief, initialed in one corner with the letter “S.” Might it stand for “Stevens”?

Around this time, Charlotte Mills said she had found a package of love letters from Edward to her mother, along with his “love diary” from the previous August. They had been hanging in a sewing bag from a doorknob in the living room of Mills’ apartment. Edward apparently had mailed his love letters directly to the Mills home.

Instead of turning these over to the police, James sold the lot for $500 to the New York

American

. Charlotte explained that since the prosecutor was not cooperating with them, they owed him no cooperation in return. She hinted that she had information about how her mother’s letters ended up at the crime scene. Inexplicably, investigators just dismissed her.

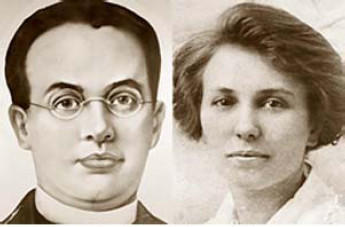

Rev. Hall and Eleanor Mills

Beekman and Stricker decided to interrogate members of both families, tardy though the questioning was. Appointments were set up for Frances, her brothers, and Charlotte. Henry Stevens drove in from the coast. He identified the handkerchief with the “S” on it as his, but insisted he had been nowhere near New Brunswick during the murders.

Frances was told to don the gray coat she had worn the early morning of Friday, September 15, the day after the murders, and to stand for the scrutiny of a woman who was present. No one explained who she was, and, after looking at Frances, she left the room without saying a word. The unidentified woman, Jane Gibson, would become an important witness at a later date.

Beekman told the press in his typically coy manner that they had obtained “new information,” but made no arrests.

Back to the crime scene: A chemist released an analysis of soil removed from beneath the bodies. These results established, from the measured volume of blood in the soil, that Mrs. Mills had been shot before her throat was cut. Also, the couple had been murdered precisely where they were found.

The investigation now belonged, undeniably, to Somerset County.

Beekman took over, although Stricker was not giving up easily. He continued to observe and to criticize.

Finally, Justice Parker of the New Jersey Supreme Court claimed jurisdiction. He deputized William A. Mott as Deputy Attorney General in charge. Mott’s top investigator was James F. Mason, and they set up headquarters in Somerville, New Jersey. Mason vowed to turn over every stone to resolve the case.