Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (31 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

Craven has described the film as growing out of his desire to take the American public’s thirst for violence to its logical conclusions. Craven believed this would expose the foundations of violence at the heart of Nixon’s silent majority. He purposefully sought to give

Last House

a photographic intensity resembling the raw footage coming from Vietnam by using high-speed, documentary-style film. The original script called for the murderers to be Vietnam veterans, while one of the slaughtered girls would die giving the “V” sign, with all its metonymic evocations of the peace movement.

52

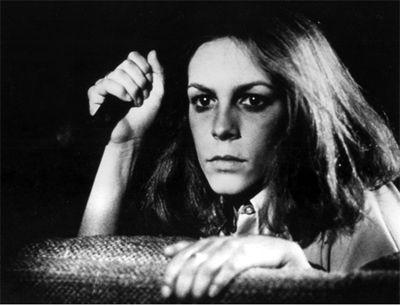

Hooper and Craven’s challenges to the dreams of America’s past and the hopes for its future were soon joined in John Carpenter’s

Halloween

(1978). Carpenter took urban legends about babysitters in danger and turned them into a critique of the American suburb. The film portrays the Halloween night return of Michael Myers, a mental patient who fifteen years earlier had brutally slashed and killed his older sister, to the small, quiet town of Haddonfield, Illinois. Pursued by psychiatrist Sam Loomis, Michael invades the quiet streets and four-bedroom ranch homes of Haddonfield, brutally slaying teenagers the same age as his sister. He meets his match in Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis, the daughter of

Psycho

’s Janet Leigh) who manages to best Michael by turning everything from coat hangers to knitting needles into weapons. Curtis’

portrayal made Strode into what horror scholar Carol Clover has described as the archetypal “final girl” of slasher convention, a gender-bending figure who slays, or at least holds at bay, the monster.

53

Jamie Lee Curtis—On the Set of

Halloween

Michael Meyers came home to a world that was supposed to be safe. Suburban life since the 1950s had increasingly become the image of middle-class success. In the master narrative of domestic life, hard work and frugality allowed an American family to purchase a suburban home that offered refuge from the world of commerce. At the same time, the home became a place to display the rewards of financial success, a showcase for the latest model of refrigerator, self-cleaning oven, and color television set.

54

The civil rights struggle had given another meaning to the suburban home. The phenomenon of “white flight” from urban centers created the perception of the suburb as an escape from social change. New school districts blossomed around the nation as the educational system integrated in the early 1970s, and new schools often became the epicenter for developing communities. The desire to flee the consequences of the freedom struggle generated the enormous and violent anger over busing, as white families who thought they had escaped their black neighbors watched their children’s court-ordered rides back to what was increasingly called “the ghetto” rather than the neighborhood.

55

Michael Myers’ assault on Haddonfield tapped into white middle-class anxieties that the secure world they had created could easily become a literal shambles. Carpenter pictures Haddonfield as in every way idyllic, except that one of its perfect families in one of its perfect homes produced a maniacal and unstoppable killer. In 1984, Wes Craven

would build on this theme with his

A Nightmare on Elm Street

. As the title suggests, a safe suburban street could easily become a slaughterhouse where, to paraphrase Malcolm X, the fulfillment of the American dream becomes a nightmare.

The legacy of the 1960s lived on in other aspects of the new American monster film. The critique of the alleged safety of the suburb is joined in the slasher film by a strong antiauthoritarian strain. The role of teenagers in these films has led many commentators to see them as parables of adolescent hormones run wild. In fact, the motif of teenagers in danger has been less an opportunity to explore adolescent sexuality than a chance to satire various kinds of established, institutionalized authority. Young people are generally left to themselves in these films, forced to cope with the monster alone. Parents, police, camp counselors, and ministers are frequently held up for ridicule as either ineffectual or participants in the mayhem.

Chainsaw

is paradigmatic in this respect, portraying countercultural teens as victimized by a family in a domestic setting—the American home turned slaughterhouse. In

Friday the 13th

, the killer turns out to be a middle-aged mom who despises the young for their treatment of her son Jason. In

Halloween

, Laurie Strode’s father (whom we see only briefly, in one scene) puts her in harm’s way by sending her to “the old Myers’ place” on an errand. In

A Nightmare on Elm Street

, the parents of an entire town endanger their children by keeping secret a horrible act of violence, the lynching of an alleged serial killer. The older generation’s acts of violence, and the secrecy that surrounds it, unleashes Freddy Krueger into the nightmares of their children.

56

Craven’s 1984

Nightmare

represents the crest of the slasher film’s creativity as a form. Independent auteurs such as Hooper, Carpenter, and Craven increasingly moved on to big-budget studio projects and left the indie slashers to lesser talents eager to cash in on the maniac with a knife craze. By the late 1980s, Reagan-era conservatism seemed to influence many of the films being made in the genre. Sequel after sequel drew less and less from their seminal sources of bloody inspiration and degenerated into simplistic morality tales of besieged communities seeking to destroy a monster, a reimagining of the themes of 1930s horror with less creativity and lots more blood and skin.

57

By the late 1980s the Reagan Revolution came to fruition in the rise of the yuppie mentality, a vision of youthful experience in which brutally ambitious MBAs fought their way to the top of corporate America. From Michael J. Fox’s Alex in television’s

Family Ties

to Michael Douglas’ Gordon Gekko in

Wall Street

, the yuppie worldview saw American

life as a wild frontier and men in Brooks Brothers suits as the new Davy Crocketts.

58

The serial killer remained the icon of this era though revisions of his image left behind some of the themes found in the slasher films. Increasingly, the monster wore the mask of success, American style.

Bret Easton Ellis’ 1991

American Psycho

transformed Norman Bates into a 1980s American yuppie turned (maybe) into a serial killer. Ellis’ novel tells the story of Patrick Bateman, a corporate-ladder- climbing monster whose obsession with the accumulation of status commodities and utter hatred of women leads him to commit a series of bizarre and brutal murders. While Ellis leaves unresolved the question of whether or not these murders actually occurred or only took place in Bateman’s mind, his graphic descriptions seem more than real to the reader.

59

Ellis’ title makes clear that Bateman represents a peculiarly “American” psycho. Bateman works for “Pierce and Pierce Mergers and Acquisitions,” a typical 1980s financial firm practicing slash-and-burn capitalism. His antifeminist obsessions and love of status symbols (a brilliant and unforgettable scene in the book and the film has Bateman wax poetic over the paper quality of his business cards) perfectly tied together the obsessions of the New Right, its freebooting entrepreneurialism, and reactionary response to the women’s movement.

60

A cult classic today,

American Psycho

had a bumpy ride to press. Simon & Schuster originally picked up

American Psycho

for publication. The rumors of the novel’s alleged misogyny set off intense and heated prepublication criticism from NOW and other women’s organizations. Simon & Schuster dropped the book one month before its planned publication date, though it was quickly picked up by Vintage Books and became a controversial best seller.

61

Ironically, during the period when Ellis’ book received a rough handling by censors at both ends of the political spectrum, images of serial murderers saturated American culture. Bateman’s deeply American psychosis mirrored a fascination with the serial killer that intertwined with the American culture of celebrity. This had been a facet of the serial killer’s appeal since Ted Bundy, whose crimes brought him enormous media attention while he waited for execution on Florida’s death row. Bundy became one of the first serial killers to create a romantic following. Women sent him flowers in prison and wrote him love letters. One admirer, Carol Anne Boone, moved from Washington state to Florida in order to be near him. They later married and had a child.

62

The growth of serial killer fandom led to the phenomenon of murderabilia, the auctioning of personal items and artwork belonging to “celebrity murderers.” The Internet helped to fuel this phenomenon. The murderabilia site murderauction.com has offered a John Wayne Gacy collection with a starting bid of ten thousand dollars, as well as less expensive single items such as a Henry Lee Lucas drawing of a vampire with a starting bid of seven hundred dollars.

63

Public obsession with serial murderers by the 1990s fed off new cultural realities. Historic changes in technology since the appearance of

Psycho

in 1960 facilitated the rise of a cult of celebrity. In the late 1960s satellite technology made possible the broadcast of multiple channels and the emergence of cable television. Entrepreneurs like Rupert Murdoch proved especially adept at transforming cable TV into one strand of a larger web of media outlets (including magazines and radio stations) that literally covered the globe. By the 1980s this media monster had become voracious for material to fill hundreds of channels playing twenty-four hours a day. The explosive growth of the Internet by the mid-1990s created an even greater need for fresh content. Serial murderers and their stories provided a simple narrative that did not ask audiences to confront larger social and political realities.

The cult of celebrity that centered on murderers invited satire. Oliver Stone’s 1994

Natural Born Killers

used the serial killer as a symbol of media madness, posing questions about the nature of the monster in a world that simultaneously hates, fears, and glamorizes the monster. Stone’s psychedelic imagery perfectly captured the frenetic pace of the twenty-four-hour news cycle. The film used the device of a TV sitcom to tell the story of one of the killer’s dysfunctional family background, mixing the inanity of a laugh track with the severe sexual and psychological abuse that allegedly created the murdering maniac.

64

The mid-1990s perhaps represent the apogee of the American fascination with serial murder. Talk shows, twenty-four-hour news outlets, true crime novels, a raft of movies, and innumerable television police procedurals dealt time and again with the knife, axe, and chainsaw-wielding maniac. This dark obsession in American culture did not disappear in the twenty-first century, although history would alter and complicate it.

Al Qaeda’s attack on the Twin Towers in 2001 gave America a new set of monsters. Anger and a desire for revenge led politicians and the public to load the terrorists down with monstrous imagery. As if ideologically inspired terrorists with no respect for human life were not fearful enough, political leaders and commentators referred to the terrorist network as a “cult of evil” and made use of satanic imagery to describe the threat. The idea of the terrorist as the monster became a common media trope.

65

Bomb-wielding terrorists did not completely replace the maniac with a knife. The 2006 Showtime hit

Dexter

recreated the serial killer for a post-9/11 world. The gruesome drama of the Emmy Award-winning series featured Dexter Morgan (played by Michael C. Hall) as a serial murderer that works by day for the Miami Police Department as a blood spatter expert. By night, he splatters quite a bit of blood on his own in the vigilante killings of “the guilty” who have slipped through the criminal justice system.

Dexter

represents both the best fiction ever produced about the serial murderer and a revisionist reading of America’s serial killer craze.

Dexter

, which has successfully run for four seasons at the time of this writing, asks the audience to identify with the serial murderer in a way that no other imaginative reconstruction of the genre has ever done before.

66

Dexter’s creators provide a significant number of cues that audiences can recognize from the national mythology of the mass murderer. We learn, for example, that Dexter endured a significant childhood trauma. Moreover, he believes, and we are urged to believe, that Dexter is a monster on a basic level. He makes numerous references to his “Dark Passenger,” a need to kill born out of a traumatic event. We also learn that Harry, his homicide investigator stepfather, recognized the signs of this inner monster in Dexter’s early childhood. Knowing that the beast could be controlled but not destroyed, he taught Dexter “the Code,” a complex mix of injunctions against killing the innocent, combined with precautionary measures to keep from getting caught.