Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (13 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

Polidori’s tale (for a time attributed to Byron himself) portrayed a very Byronesque character named Lord Ruthven who becomes a vampire after his death. As in German versions of the vampire legend, Ruthven searches for a forbidden bride (a motif that appears in Bram Stoker’s masterwork). Theatrical versions of “The Vampyre” became common, and it eventually worked its influence over Stoker’s tale in the 1890s.

18

Vampires would take some time to make their way to the United States but the other monstrous creation of that Swiss holiday more quickly shambled ashore. While Polidori dreamed of bloodsucking (and sexy) freaks, young Mary Shelley had nightmares of “the pale student of the unhallowed arts kneeling beside the Thing he had put together.”

Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus

would be first published in 1818 and would see quick, trans-Atlantic success.

19

“In less than a decade,” writes Susan Tyler Hitchcock, author of an important cultural history of Shelley’s tale, “

Frankenstein

had penetrated the public imagination and had become a story told, retold and reinterpreted.” Theatrical productions of Shelley’s monster story appeared in America as early as 1825. Her dark tale influenced a fascination in American pulp literature with dissection and dismemberment as well as the horrors of resuscitated life. Lurid American novels, such as John Hovey Robinson’s

Marietta; or, The Two Students: a Tale of the Dissecting Room and “Body Snatchers”

(1842), drew on the imagery of Frankenstein while also reflecting a debate in the emerging American medical profession over the ethics of dissection.

20

Although born of the same cultural moment, Frankenstein’s monster and the vampire are quite distinct horrors. The Creature is born in a lab and his creation is an industrial process; an assembling of parts. The vampire has clear supernatural origins in devil worship and black magic. He is not the creation of the Industrial Revolution but a memory of the times before it, a dark nostalgia. Differences aside, the fascination with both monsters grew out of the rapidly changing conditions of early capitalism. The Industrial Revolution seemed to suggest that technology had become Dr. Frankenstein, unleashing monsters to walk the earth. A society where technology had seemingly taken the place of the divine raised questions about the nature of the supernatural, questions that the vampire answered in terrifying fashion.

21

American readers took much more quickly to Frankenstein’s monster. The rapid changes brought by the market revolution created significant nervousness in the American public. This theme in Frankenstein,

especially when combined with the obvious metaphors of enslavement and rebellion, touched a cord in American audiences. Literary scholar Elizabeth Young shows that the image of Frankenstein as rebellious slave not only appears in relation to white anxiety over the Nat Turner Rebellion but also becomes “the embodiment of racial uprising” in political rhetoric and imagery. The story of a “monster” that rebelled against its master offered a very explicit metaphor for nervous whites.

22

The vampire would, appropriately, only lurk in the American shadows through most of the nineteenth century. However, he made his influence felt in ways that point to what would become his rock star status in twentieth-century American pop culture. For example, a number of Poe’s tales feature a vampire that lives off the psychic energy, if not the blood, of its victims. At least one unpublished vampire novel of the 1870s drew on the same European influences that were later so important to Stoker in the 1890s.

23

The American turn toward the gothic, with its dark castles and shambling creatures, represents only one facet of the nation’s monster obsession. America remained a settler society throughout much of the nineteenth century, expanding its frontier and seeking to secure a profit on the seas. Monsters of the deep appeared both in frontier lakes and along its coasts, frightening and appalling but also delighting the new nation. Not surprisingly for a seaboard nation tied to the economic engine of the Atlantic world, monsters from the depths haunted the waters.

Melville’s Monster

One of America’s greatest horror writers would reflect on the terrors of the seas. Early twentieth-century pulp writer H. P. Lovecraft’s short story “Dagon” tells the tale of a marooned sailor during the First World War who comes upon a strange megalith on a seemingly deserted island. Under “a fantastically gibbous moon” the sailor sees that the stone is covered in images of horrifying creatures who “were damnably human in general outline despite webbed hands and feet, shockingly wide and flabby lips, glassy bulging eyes and other features less pleasant to recall.” Already unsettled by these images, the unnamed sailor is then driven insane when “a stupendous monster of nightmares” slides out of the sea and embraces the monolith.

24

Lovecraft became a master at creating inhuman horrors connected to the ocean. His famous short story “The Call of Cthluhu” imagines a gigantic, apocalyptic monster sleeping beneath the waves, waiting for the stars to align so that it can rise and destroy all human society. In other tales, creatures from other dimensions, called forth by equally

monstrous humans, wreak havoc and threaten the existence of human life on earth. Terror in Lovecraft’s conception came from a philosophical sentiment in which human beings are expendable and unimportant rather than direct victims and prey. The vast heavens and the equally vast deeps contained monsters that will unthinkingly destroy us.

The American sea serpent of the early nineteenth century was a much less frightening creature. In no way did it represent a beast that could upset the order of things. The serpent instead became the center of scientific debate, playing a role in discussions about the nature of geological change and evolutionary biology. By extension, “serpent sightings” and their meaning became the basis for an emerging war between amateur and professional conceptions of science and a debate over the nature of scientific evidence. The creature also came to occupy a central place in American popular culture in what would become a well-worn path for the monster. In the United States, every frightening apparition and ravening beast has had an afterlife as a media celebrity.

Antebellum America remained fascinated with monsters of the deep long after the sightings of the sea serpent off Gloucester harbor. Between 1800 and 1850, American monster watchers reported over one hundred and sixty-six sightings of alleged sea serpents, both on the high seas and in American lakes. A market in fossils developed as monster hunters claimed to locate the remains of sea serpents in all parts of the new nation.

25

Sea serpent mania generated a significant amount of scientific interest. Debates over the existence of the creature claimed the attention of important nineteenth-century scientists, including Charles Lyell. Best known for his work on geology that complemented Darwin’s theory of evolution, Lyell collected numerous eyewitness accounts of the creature and, at one particularly enthusiastic moment, claimed that these accounts had caused him to “believe in the sea serpent without ever having seen it.”

26

The Boston Linnean Society shared Lyell’s interest, and after the 1817 Massachusetts sightings, began a serious effort to compile accounts and work up a zoological profile of the sea serpent. In their zeal to find definitive evidence for the creature, members of the society became convinced that a three-foot snake with strange markings represented one of the sea serpent’s young. This alleged find encouraged the speculation that the Gloucester serpent had come close to shore to spawn. Early American newspapers widely reported the society’s claims, causing significant embarrassment when further investigations by Harvard zoologist Louis Agassiz revealed the creature as a fairly common land snake

with a disease that gave it strangely raised bumps. The debacle helped lead to the dissolution of the Boston society in 1822.

27

This embarrassment for the New England natural history community did nothing to dampen the broader American enthusiasm for sea monsters that reached fever pitch by midcentury. In 1852 the American whaling ship

Monangahela

allegedly sighted a sea serpent over one hundred feet in length in the South Pacific. The ship’s captain, whose reports from sea filtered in to American newspapers throughout the year, described an epic chase in which the giant creature, after being hit with multiple harpoons, pulled the ship for sixteen hours before dying. In his letters to major American magazines, the captain promised to sail into New York harbor with the remains of the sea beast. The excitement over the serpent resulted in multiple stories in the

New York Times

and the

New York Tribune

. Unfortunately, the

Monongahela

was reported lost in the arctic seas in 1853.

28

Nineteenth-century belief in the sea serpent became a profession of faith in the unknowability of nature combined with, ironically, the willingness to accept unconfirmed personal experience (“eyewitness accounts”) as evidence. Belief in the creature lost traction by the second half of the century as scientists fully professionalized their disciplines by placing their work under the umbrella of major universities. Here they would form organizations that would issue credentials based on educational requirements and publish journals that vetted scientific research through the judicial process of peer review. These standards of proof replaced subjective experiences and alleged “eyewitness reports” in determining empirical truths.

The sea serpent fell back into the realm of myth in the wake of emerging scientific consensus about the nature of evidence. Contemporary historian Sherrie Lynn Lyons, in her detailed examination of this debate, describes how the sea serpent came to be seen as an insoluble problem by American science. No specimen of the creature existed. The numerous sightings and affidavits for the creature’s existence failed to meet established standards for discerning truth. Given these facts, science refused to say that sea monsters did not exist, but simply pointed out that the lack of fossil evidence or specimens to analyze in controlled settings made it impossible to assert that such a creature did exist.

29

Popular culture in the United States refused to shed its enthusiasm for the sea serpent as a source of entertainment and wonder, despite the scientific community’s refusal to credit its existence. In the second half of the nineteenth century, sea beasts may have been, by far, the most popular American monster. Their alleged existence offered Victorian America a sense of wonder at the marvelous unknown and even seemed

to strengthen and support religious belief. Sea serpent entrepreneurs could claim that the serpent was not only a natural animal, but a supernatural visitation, perhaps even one of the marvelous, unknown creatures described in scripture as Leviathan. Such ideas proved attractive to religious Americans who felt their beliefs about nature to be under assault after the emergence of Darwinian evolutionary theory.

Promoters quickly claimed fossil finds on an Alabama plantation in 1842 as evidence for a sea monster with sacred meaning. Herman Melville wrote in

Moby-Dick

about these remains, reporting the story that “credulous slaves in the vicinity took it for one of the bones of the fallen angels.” In fact, credulity was not limited to Alabama slaves when it came to these fossils. In 1845 a carnival promoter exhibited them in New York and New England, placed in an undulating shape, with head raised. This was the same physical position as most artistic renderings of serpent sightings in Gloucester harbor.

30

Advertising copy for the Alabama sea monster claimed that carnival goers would see a creature one hundred and fourteen feet in length. Handbills asserted that the creature did not represent a scientific specimen, but rather a sign rich with theological meaning. The advertisement for the beast went back to Ezra Stiles’ doctrine of monsters by claiming the creature to be Leviathan from the book of Job. In fact, scientists later concluded that the carnival monster represented an achievement

of ingenious taxidermy, a human construction made out of at least five different types of fossil remains.

31

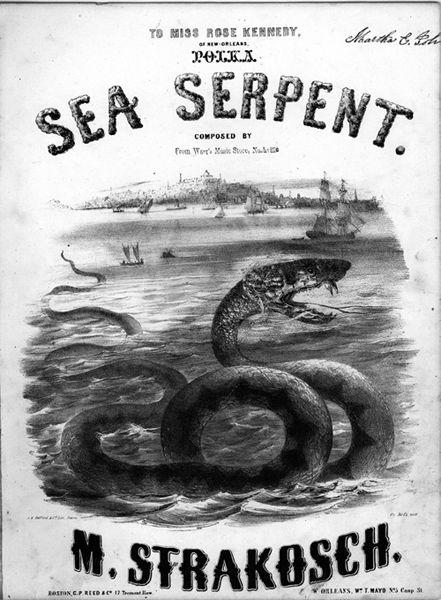

Exhibitions such as these underscore how much the sea serpent became a celebrity. Significant sightings became embedded in American popular culture of the period. An original composition known as the “Sea Serpent Polka” became a popular piece of sheet music, its cover replicating the image of the serpent well known from the Gloucester sightings and reenacted by carnival exhibitors. Captains, meanwhile, christened their ships “Sea Serpent” and sightings of similar creatures in America’s lakes became common.

32