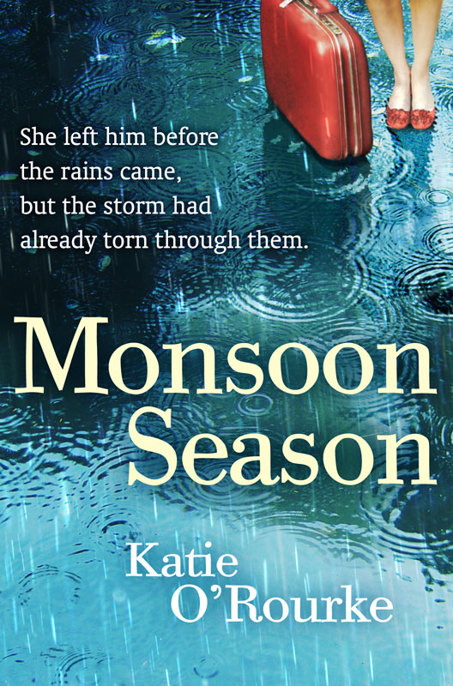

Monsoon Season

Authors: Katie O’Rourke

Katie O’Rourke lives in Tucson, Arizona, where she was inspired to write her first novel,

Monsoon Season

. Katie is currently renovating her new home, painting, and working on her next novel.

Katie O’Rourke

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Canvas,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2012

Copyright © Katie O’Rourke, 2012

The right of Katie O’Rourke to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual events or locales is entirely coincidental.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-78033-693-0

Printed and bound in the UK

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For my family, the one I was born into and the one I created, for teaching me everything I know about love.

Special thanks to my mother, whose storytelling has shaped my writing and my life.

RILEY

As soon as the bus pulled out of the station, I set my book in my lap. I’d already read the same sentence half a dozen times. I felt intensely aware of my body: the position of my legs (uncrossed), my feet on the metal bar in front of me, my palms face down on the pages of the open book. I was sitting up straight, as you have to in those kinds of seats, with my head tilted to the right so I could pretend to be looking out of the window. I feel like you always have to pretend to be looking at something when what you’re really doing is thinking about the tragedy of your own life. Otherwise people tend to assume that you’re crazy – whether you’re accidentally staring at someone or you seem to be casually examining the fabric of the seat in front of you. Looking out of the window is a pretty harmless occupation for your eyes. It makes people more comfortable.

I sat two rows from the front, my backpack on the seat next to me. It’s all part of my bus strategy. I pretend to be consumed by whatever book I’m reading so that other passengers won’t ask me to move my bag and let them sit next to me. It only works if you’re near the front. By the time they get to the back of the bus, they’ve run out of options.

Since leaving Tucson, I had been waiting for some kind of sign, or feeling that I was doing the right thing. The flight from Phoenix to Boston had been direct and unsettling. Humans aren’t meant to travel at that speed. There isn’t time for your mind to catch up with the idea of your body being in a new place. It isn’t natural. Sitting on this bus, my unfocused gaze vaguely registering the blur of trees along the Massachusetts Turnpike, I began to feel myself breathing for what seemed like the first time in days. I had been operating on autopilot so long that it came as a great relief, a startling realization, that I was alive. I was choosing this breath and then the next.

My hand cupped the side of my face, my fingertips exploring the slope of my cheekbone. There was no bruising, and although this meant fewer questions to answer, it seemed wrong, the absence of physical proof to confirm my reality. I felt black and blue all over.

That morning I’d sat across from Donna at the kitchen table. It was a lime-green diner table from the fifties. We’d picked it up from Craig’s List because it reminded Donna of one her grandmother had. The chairs didn’t match it or each other and the vinyl on mine had split along the edge showing the beige foam padding within, like a deep gash in human flesh.

I blew into my coffee mug, aware of Donna’s eyes on me. Reluctantly, I looked up at her. ‘Cry.’ She said it like it was an order.

I shrugged, looking back into my coffee.

‘I feel like you’re trying to hold it together for my sake, but I’d much rather you just fell apart.’

‘I’m sorry.’

Donna rolled her eyes. ‘Yeah. That’s what I want.’

I took a big swallow of coffee. ‘I broke a bowl this morning.’

‘Which one?’

‘The one with the chip in it.’

‘That’s kind of lucky.’

‘Yeah. I like to finish what I start.’

Donna laughed.

‘Don’t ever let it be said that I’m not tougher than an inanimate object.’

‘I wouldn’t dare.’ She sighed. ‘So your parents know you’re coming?’

‘Yeah. I sent an email first to tell them I got a cheap deal on a last-minute flight. I lie better in email.’

She nodded.

I chewed at a hangnail on my thumb. ‘So, am I the biggest loser you know?’

Donna reached across the table and grasped my wrist. ‘No, not the biggest.’

We smiled at each other.

I’d always wanted to live in Tucson. Ever since I’d seen Drew Barrymore and Whoopi Goldberg in

Boys on the Side

. They lived in this amazing adobe house, and the Indigo Girls played at the local cantina. With my college graduation approaching, and my classmates getting jobs, or at least going for interviews, I spent a lot of time thinking about Tucson. My father’s voice played in my head as I looked at Internet ads for roommates there: ‘What are you going to do with a major in philosophy?’

Somehow it had never occurred to me that, when I left school, I’d need to be marketable. I took classes that interested me; I read books my parents had never heard of, contemplated things they’d never considered. I discussed complex theories in the dining hall, eating food I hadn’t paid for. I stayed up late debating fascinating ideas, knowing I could sleep until noon the next day. I’d change the world eventually, but I never thought about how I’d pay the rent until then. I’d never really given much thought to the end of college. My graduation loomed ahead of me, like an appointment to fall off a cliff to my death. And it was a kind of death. I would never be this free again.

That was how I met Donna. She was a bartender in Tucson and the girl she’d been living with had married rather suddenly and moved out. She was barely able to cover the rent on her own. We emailed back and forth for a while, and I got a really good feeling about her. The fact that I ended up being right could have been a complete lucky coincidence. It seems I’ve been right about people about as often as I’ve been wrong.

I took the graduation money my grandfather had given me and one suitcase and took off a week after the ceremony. My parents and I had several arguments about it before I left. I couldn’t give them a satisfactory adult reason for leaving, but when I told them I’d already purchased my plane ticket, they backed off. They seemed to decide it might finally be time to let me make my own mistakes. I think they believed I’d be back in a matter of weeks.

Tucson isn’t really like it is in the movie. They must have filmed on the edge of town, or outside town, because things aren’t so spread out and there aren’t that many dirt roads. Most of the roads are four lanes travelling in each direction. Everything is on a grid and each street corner looks the same as the next. Everyone talks about cross streets. In New England, we always give directions that are three pages long and include things like ‘Turn left after the blue house.’ In Tucson, you just tell people the two roads that intersect closest to your address. Simple as that.

Donna picked me up at the airport in Phoenix. I recognized her immediately. I hadn’t been sure about that even though she’d sent me a picture. You never know how well a photograph represents the real person. I wonder sometimes whether I look the same as I do in pictures. People have always told me that I’m very photogenic. I take that to mean I don’t look as good in reality.

Donna had curly red hair and a nice tan. She didn’t have fair skin, the way a lot of redheads do: a girl like that couldn’t live in Arizona. She was waiting for me at Baggage Claim and she ran up and hugged me. I felt like we were old friends who hadn’t seen each other in a while. She insisted on carrying my bag out to the car and I insisted on paying for the parking and we chatted non-stop all the way to Tucson. I don’t remember what we talked about.

Donna got me a job as a waitress at the restaurant where she tended bar. Even though I’d never worked as a waitress before, her recommendation was enough. It was hard work, but I liked getting to talk to people all day. I thought of it as temporary; something to do until I got my bearings. It’s a good way to get the feel of a new city. When Donna and I worked the same shift, I’d get a ride with her, and when we didn’t, I’d take the bus. It all worked out.

When I called home, I didn’t get a lot of enthusiasm for my new job.

‘You’re working as a waitress?’ my father asked me, repeating the exact words I had just said, only in the form of a question. When he passed the phone to my mother she asked if I was planning on finding myself in the soup of the day.

‘You never know,’ I said, determinedly cheerful.

I knew it could have been worse. They had paid for my degree and all they expected in return was for me to have the kind of future that would impress the recipients of my mother’s Christmas-card updates.

I didn’t call home very often.

I met Ben at work on a Friday night. I’d only been in Tucson for a few weeks. He ordered a bacon cheeseburger and a Coke. It wasn’t the soup of the day, but as soon as we locked eyes, I had the feeling I’d found something I hadn’t even known I’d been looking for.

I waited for his friend to go to the restroom, then dropped by his table. ‘How is everything?’ I asked.

‘Fine. Everything’s fine.’ He reached for his glass, but didn’t lift it from the table.

‘Just fine? Not great?’ I looked at him with mock-concern, one hand on my hip.

He smiled. ‘Now that I think about it, everything’s great. Thanks.’

I smiled back. ‘That’s better.’

‘I haven’t seen you here before,’ he said. He was wearing faded blue jeans and a white T-shirt, speckled with yellow paint. He had an even, dark tan, and though his clothing and muscled arms spoke of hard work, his fingernails were short and clean.

‘It’s my first week. I just moved here,’ I said.

‘Oh? Where you from?’

‘Massachusetts.’

‘Wow. What brought you out here?’

‘Well, the job mostly.’

His brow furrowed.

‘I’m kidding.’

He laughed. ‘Sorry. I’m gullible.’

‘I’ll keep that in mind.’ I was clicking the top of my pen in and out. ‘I just felt like a change, really.’

‘Well, I’d say you’re in for one.’ He leaned forward in his seat. ‘You know, if you’re looking for someone to show you around—’ He cleared his throat.

‘Oh, yeah? What are your tour-guide credentials?’

‘Well, I’ve lived here all my life.’

‘That’s a pretty good one.’

‘I’m Ben, by the way.’

‘Riley,’ I said, angling my shoulder toward him and motion -ing to my nametag.

Ben slid his napkin to me. ‘Why don’t you give me your number?’

I held out my pen. ‘Why don’t you give me yours?’

Ben was writing as his friend returned to the table, raising his eyebrows and smirking. I stuffed the napkin into my apron, told them to enjoy their meals and left.

I called Ben two days later and he took me up Mount Lemmon. He told me there were five different ecosystems along the drive, but we counted only three. It was amazing the way the environment shifted so quickly: after miles of saguaro cactuses in all directions, I couldn’t find a single one.

Ben had dark hair and green eyes. He had certain smiles he only ever gave to me. When we ate at my place, he would clear the table and rinse the dishes so it wouldn’t be such a chore for me later. He wore short sleeves on cool evenings, but always brought his jacket along in case I got cold. He thumbed through the pages of the books piled on my nightstand. He readjusted the blankets in the middle of the night, sitting up to make sure my feet were covered. He told stories like it was the first telling, like I was the only one he’d ever told.