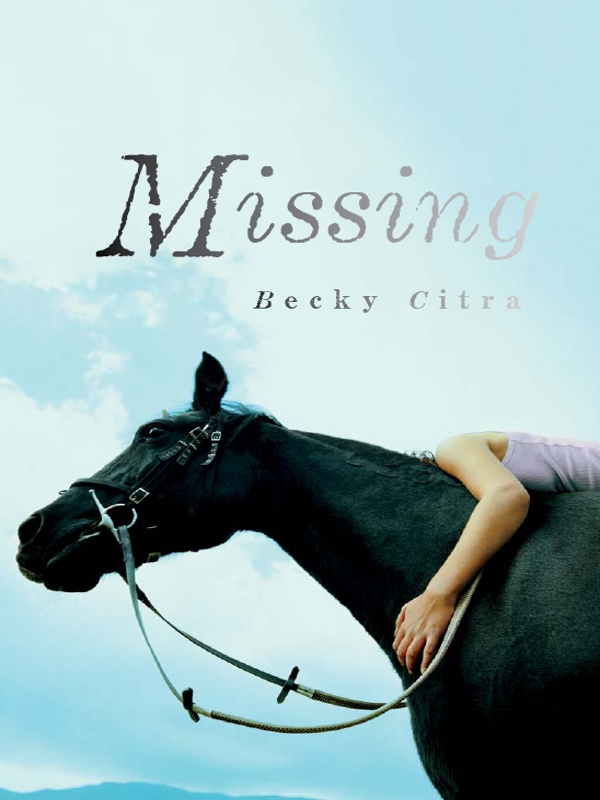

Missing

M

issing

B

ecky

C

itra

ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS

Text copyright © 2011 Becky Citra

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Citra, Becky

Missing [electronic resource] / Becky Citra.

Type of computer file: Electronic monograph in PDF format.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-55469-346-7

I. Title.

PS8555.I87M58 2011A Â Â Â Â Â JC813'.54 Â Â Â Â Â C2010-907947-7

First published in the United States, 2011

Library of Congress Control Number

: 2010941924

Summary

: When Thea's father gets a job at a guest ranch in the Cariboo, Thea earns the trust of an abused horse, solves an old mystery and makes a new friend.

Orca Book Publishers is dedicated to preserving the environment and has printed this book

on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council.

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs provided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Cover design by Teresa Bubela

Text design and typesetting by Jasmine Devonshire

Cover photography by Getty Images

| ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS | ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS |

| PO B OX 5626, S TN. B | PO B OX 468 |

| V ICTORIA, BC C ANADA | C USTER, WA USA |

| V8R 6S4 | 98240-0468 |

www.orcabook.com

Printed and bound in Canada.

14  13  12  11  ⢠  4  3  2  1

For my brother John

Contents

It's nearly the end of June, and I'm at the café, sitting in my usual booth at the back. I must look like the biggest loser. Nowhere to go after school but the café, where I work on homework. Not that there's anyone to see me. No one that matters anyway.

“How's the homework going?” says Dad. He's wiping the table in the booth next to mine, scrubbing at a particularly stubborn ketchup blob. Usually he's behind the grill, frying burgers and eggs, but the waitress has gone home early with a headache. Dad's boss, Sid, took over the grill and sent Dad out here. The café is mostly empty; there's just a woman and a small child eating ice cream at the window table.

Dad lingers to chat. “Want a Coke?”

“No thanks.”

“School go okay today?”

“Great,” I lie.

I don't fool Dad. “Give it a chance,” he says. “You can't expect to have a lot of friends instantly.”

I bend over my book so I don't have to lie anymore. Dad doesn't know what he's talking about. It takes time to make friends, and that's what I don't have. Sid's regular cook will be back next week and then Dad will be officially out of work. Again. He's been scanning the newspaper for jobs for weeks and leaving resumes around town, but there's nothing here. We'll be moving again.

And since when does Dad care anyway?

The page of math problems blurs over, and I blink hard. I've been like this all day. Fragile.

“Hey, Dusty, get in here,” calls Sid. Dad's jaw tightens for a moment. I guess he isn't having the best day either. He takes his time going back to the kitchen, and I concentrate on the next math problem.

Now I really feel like crying. I have a whole page of these stupid problems to do. I think longingly of the novel that I borrowed from the school library.

The Horse

Whisperer

. I've seen the movie three times, but I've never read the book. For some reason, I didn't know there was a book, and it was the best moment of my week when I spotted it in the trolley of books waiting to be shelved. It's fat, and I figure I should really save it for school. It would fill up a lot of empty lunch hours.

I turn back to my math book. Who makes up these problems? What do they have to do with real life? An hour later I've done as much as I can, which is a little less than half. I'm already behind in all my subjects, and my worst nightmare is that I fail grade eight and have to do it all over again. I've always thought of myself as an average student, but this school is way harder than the last one.

When we lived in the Fraser Valley, I went to the same school from kindergarten to grade four. I liked it a lot, and I had three best friends. After all the bad stuff happened, Dad didn't want anything to do with our old life. We came north and started moving from small town to small town in the Cariboo. That's when things got even worse. None of Dad's jobs last, and I want to go back to our old life, but I know Dad never will. I still miss my friends, though they've probably forgotten all about me, and I miss the Valley.

The café is empty now, except for Sid, Dad and me. Dad slides onto the seat opposite me with a mug of coffee. His face looks gray. Sid gives him ten-minute breaks and if Dad takes even one gazillionth of a second longer, Sid starts griping about how the café isn't made of money. It's the end of the night, so it's Dad's last break. Then he'll clean up the kitchen and we can go home.

The door opens and a man comes in. He's a big man with a red face, wearing jeans and boots that look brand-new, and a cowboy hat that doesn't fit his head quite right. Dad has his back to him and he doesn't turn around. A customer at this time of night means the café will be late closing. Sid doesn't ever turn down the chance to make some money.

But Sid wants to go home tooâthe air-conditioning is on the fritz and there are two half circles of sweat under his armpits. “Sorry, we're closing,” he says.

The man smiles and says, “I'm not here for a meal. I'm just spreading the word around town that I'm looking to hire someone out at my ranch. You must get a lot of people in and out of here during the day. Know anyone who's looking for work?”

Dad's listening now, I can tell, even though he's pretending to drink his coffee. As for me, I want to scream, “Yes! Over here!” I can't believe this. Some guy just wanders in here with a job tucked in his pocket. I don't even care what the job is. I'm sure Dad can do it. Maybe, just maybe, we can stay in one town for more than a few months.

Sid nods his head our way and says, “You might want to talk to Dusty.”

The man hesitates for a second and then approaches our table. He reaches out his hand and says in a loud voice, “Stan Tulworth. Everyone calls me Tully.”

Dad says, “Dusty Taylor.” He shakes hands and then adds, “And this is my daughter, Thea.”

“Thea. What a charming name. Short for Theadora?”

I nod, slightly embarrassed. Most people have never heard of the name Theadora. I'm hoping Tully will say more about the job. I'm trying to stay cool inside, but I can hear my heart thumping. I'm feeling so hopeful, but I should know better by now.

“Pleased to meet you both,” says Tully. “Can you give me a few minutes of your time?”

Dad shrugs and Tully, taking that for a yes, slides his bulk into the seat beside me. He spreads his hands on the table. He's wearing a large silver ring with a chunky black stone. “I bought the Double R Ranch,” he says without any preamble.

“Is that so?” says Dad.

“So you've heard of the place?” Tully asks.

Dad shakes his head. “Sorry. We're fairly new in town ourselves.”

Tully exhales loudly. “It's a big spread up on Gumboot Lake, about twenty kilometers out of town. A guest ranch. There's ten cabins along the lakeshore and a lodge. Last owner got rid of the horses and closed it up about three years ago. Put a caretaker in there while he kept it on the market.” Tully beams. “Then I bought it. In April.”

Dad takes a sip of his coffee.

“Thing is,” says Tully, “I'm planning to bring the guests back and breed quarter horses as well. Highquality horses.”

“You run a ranch before?” says Dad.

“No,” says Tully. “But I like a challenge.”

“Ah,” says Dad.

“The horses will have to wait until next summer,” says Tully. “This year I'm focusing on fixing the place up. Most of the cabins are pretty run-down. I'm looking for someone with some carpentry skills. I want to gut at least three of the cabins and fix them up real nice.”

I don't tend to think of Dad and me as lucky. But this is our lucky night. Dad is really good at building stuff, and he likes it way better than cooking hamburgers. My breath comes out in a whoosh. “Dad built a whole house once,” I say. It's true. It took eight months and it was the longest I had stayed in one school since I was nine.

“Is that so?” says Tully.

But Dad says, “I don't know.”

I know right away what he's thinking. It's the talk about horses. Ever since Mom's accident four years ago, Dad can't even stand to think about horses. I don't get how Dad can wipe out a whole part of our lives, but he has. He changes the subject if I even mention horses. A lump fills my throat.

Tully is waiting and Dad says, “I don't know,” again.

Tully takes a wallet out of his back pocket, opens it and slides out a business card. He lays it on the table. “Here's my card. I'll be around the ranch all next weekend. Come on out and we can talk.”

Tully stands up, shakes hands with Dad again, and then he's gone. Tully doesn't know Dad from a hole in the wall, but he has more or less just offered him a job. I'm trying to figure out what this means. If I were religious, maybe I'd think Tully was some kind of guardian angel. But I'm not, so I don't know what to think.