Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children (3 page)

Read Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children Online

Authors: Ransom Riggs

Tags: #Mystery, #Fantasy, #Young Adult, #Paranormal, #Horror, #Thriller

The street ended at a wall of scrub pines and Ricky hung a sharp left into my grandfather’s driveway. He cut the engine, got out, and kicked my door open. Our shoes hushed through the dry grass to the porch.

I rang the bell and waited. A dog barked somewhere, a lonely sound in the muggy evening. When there was no answer I banged on the door, thinking maybe the bell had stopped working. Ricky swatted at the gnats that had begun to clothe us.

“Maybe he stepped out,” Ricky said, grinning. “Hot date.”

“Go ahead and laugh,” I said. “He’s got a better shot than we do any night of the week. This place is crawling with eligible widows.” I joked only to calm my nerves. The quiet made me anxious.

I fetched the extra key from its hiding place in the bushes. “Wait here.”

“Hell I am. Why?”

“Because you’re six-five and have green hair and my grandfather doesn’t know you and owns lots of guns.”

Ricky shrugged and stuck another wad of tobacco in his cheek. He went to stretch himself on a lawn chair as I unlocked the front door and stepped inside.

Even in the fading light I could tell the house was a disaster; it looked like it’d been ransacked by thieves. Bookshelves and cabinets had been emptied, the knicknacks and large-print

Reader’s Digests

that had filled them thrown across the floor. Couch cushions and chairs were overturned. The fridge and freezer doors hung open, their contents melting into sticky puddles on the linoleum.

My heart sank. Grandpa Portman had really, finally lost his mind. I called his name—but heard nothing.

I went from room to room, turning on lights and looking anywhere a paranoid old man might hide from monsters: behind furniture, in the attic crawlspace, under the workbench in the garage. I even checked inside his weapons cabinet, though of course it was locked, the handle ringed by scratches where he’d tried to pick it. Out on the lanai, a gallows of unwatered ferns swung browning in the breeze; while on my knees on the astroturfed floor I peered beneath rattan benches, afraid what I might discover.

I saw a gleam of light from the backyard.

Running through the screen door, I found a flashlight abandoned in the grass, its beam pointed at the woods that edged my grandfather’s yard—a scrubby wilderness of sawtoothed palmettos and trash palms that ran for a mile between Circle Village and the next subdivision, Century Woods. According to local legend, the woods were crawling with snakes, raccoons, and wild boars. When I pictured my grandfather out there, lost and raving in nothing but his bathrobe, a black feeling welled up in me. Every other week there was a news story about some geriatric citizen tripping into a retention pond and being devoured by alligators. The worst-case scenario wasn’t hard to imagine.

I shouted for Ricky and a moment later he came tearing around the side of the house. Right away he noticed something I hadn’t: a long mean-looking slice in the screen door. He let out a low whistle. “That’s a helluva cut. Wild pig coulda done it. Or a bobcat maybe. You should see the claws on them things.”

A peal of savage barking broke out nearby. We both started then traded a nervous glance. “Or a dog,” I said. The sound triggered a chain reaction across the neighborhood, and soon barks were coming from every direction.

“Could be,” Ricky said, nodding. “I got a .22 in my trunk. You just wait.” And he walked off to retrieve it.

The barks faded and a chorus of night insects rose up in their place, droning and alien. Sweat trickled down my face. It was dark now, but the breeze had died and somehow the air seemed hotter than it had all day.

I picked up the flashlight and stepped toward the trees. My grandfather was out there somewhere, I was sure of it. But where? I was no tracker, and neither was Ricky. And yet something seemed to guide me anyway—a quickening in the chest; a whisper in the viscous air—and suddenly I couldn’t wait another second. I tromped into the underbrush like a bloodhound scenting an invisible trail.

It’s hard to run in a Florida woods, where every square foot not occupied by trees is bristling with thigh-high palmetto spears and nets of entangling skunk vine, but I did my best, calling my grandfather’s name and sweeping my flashlight everywhere. I caught a white glint out of the corner of my eye and made a beeline for it, but upon closer inspection it turned out to be just a bleached and deflated soccer ball I’d lost years before.

I was about to give up and go back for Ricky when I spied a narrow corridor of freshly stomped palmettos not far away. I stepped into it and shone my light around; the leaves were splattered with something dark. My throat went dry. Steeling myself, I began to follow the trail. The farther I went, the more my stomach knotted, as though my body knew what lay ahead and was trying to warn me. And then the trail of the flattened brush widened out, and I saw him.

My grandfather lay facedown in a bed of creeper, his legs sprawled out and one arm twisted beneath him as if he’d fallen from a great height. I thought surely he was dead. His undershirt was soaked with blood, his pants were torn, and one shoe was missing. For a long moment I just stared, the beam of my flashlight shivering across his body. When I could breathe again I said his name, but he didn’t move.

I sank to my knees and pressed the flat of my hand against his back. The blood that soaked through was still warm. I could feel him breathing ever so shallowly.

I slid my arms under him and rolled him onto his back. He was alive, though just barely, his eyes glassy, his face sunken and white. Then I saw the gashes across his midsection and nearly fainted. They were wide and deep and clotted with soil, and the ground where he’d lain was muddy from blood. I tried to pull the rags of his shirt over the wounds without looking at them.

I heard Ricky shout from the backyard. “I’M HERE!” I screamed, and maybe I should’ve said more, like

danger

or

blood

, but I couldn’t form the words. All I could think was that grandfathers were supposed to die in beds, in hushed places humming with machines, not in heaps on the sodden reeking ground with ants marching over them, a brass letter opener clutched in one trembling hand.

A letter opener. That was all he’d had to defend himself. I slid it from his finger and he grasped helplessly at the air, so I took his hand and held it. My nail-bitten fingers twinned with his, pale and webbed with purple veins.

“I have to move you,” I told him, sliding one arm under his back and another under his legs. I began to lift, but he moaned and went rigid, so I stopped. I couldn’t bear to hurt him. I couldn’t leave him either, and there was nothing to do but wait, so I gently brushed loose soil from his arms and face and thinning white hair. That’s when I noticed his lips moving.

His voice was barely audible, something less than a whisper. I leaned down and put my ear to his lips. He was mumbling, fading in and out of lucidity, shifting between English and Polish.

“I don’t understand,” I whispered. I repeated his name until his eyes seemed to focus on me, and then he drew a sharp breath and said, quietly but clearly, “Go to the island, Yakob. Here it’s not safe.”

It was the old paranoia. I squeezed his hand and assured him we were fine, he was going to be fine. That was twice in one day that I’d lied to him.

I asked him what happened, what animal had hurt him, but he wasn’t listening. “Go to the island,” he repeated. “You’ll be safe there. Promise me.”

“I will. I promise.” What else could I say?

“I thought I could protect you,” he said. “I should’ve told you a long time ago ...” I could see the life going out of him.

“Told me what?” I said, choking back tears.

“There’s no time,” he whispered. Then he raised his head off the ground, trembling with the effort, and breathed into my ear: “Find the bird. In the loop. On the other side of the old man’s grave. September third, 1940.” I nodded, but he could see that I didn’t understand. With his last bit of strength, he added, “Emerson—the letter. Tell them what happened, Yakob.”

With that he sank back, spent and fading. I told him I loved him. And then he seemed to disappear into himself, his gaze drifting past me to the sky, bristling now with stars.

A moment later Ricky crashed out of the underbrush. He saw the old man limp in my arms and fell back a step. “Oh man. Oh Jesus. Oh

Jesus

,” he said, rubbing his face with his hands, and as he babbled about finding a pulse and calling the cops and did you see anything in the woods, the strangest feeling came over me. I let go of my grandfather’s body and stood up, every nerve ending tingling with an instinct I didn’t know I had. There was something in the woods, all right—I could feel it.

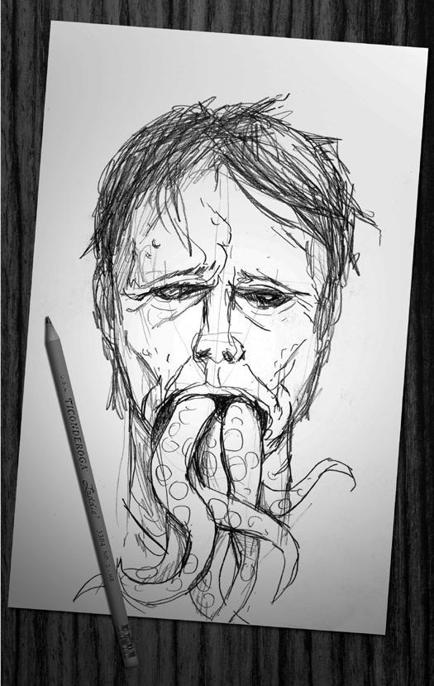

There was no moon and no movement in the underbrush but our own, and yet somehow I knew just when to raise my flashlight and just where to aim it, and for an instant in that narrow cut of light I saw a face that seemed to have been transplanted directly from the nightmares of my childhood. It stared back with eyes that swam in dark liquid, furrowed trenches of carbon-black flesh loose on its hunched frame, its mouth hinged open grotesquely so that a mass of long eel-like tongues could wriggle out. I shouted something and then it twisted and was gone, shaking the brush and drawing Ricky’s attention. He raised his .22 and fired,

pap-pap-pap-pap

, saying, “What was that? What the hell was that?” But he hadn’t seen it and I couldn’t speak to tell him, frozen in place as I was, my dying flashlight flickering over the blank woods. And then I must’ve blacked out because he was saying

Jacob, Jake, hey Ed areyouokayorwhat

, and that’s the last thing I remember.

Chapter Two

I spent the months following my grandfather’s death cycling through a purgatory of beige waiting rooms and anonymous offices, analyzed and interviewed, talked about just out of earshot, nodding when spoken to, repeating myself, the object of a thousand pitying glances and knitted brows. My parents treated me like a breakable heirloom, afraid to fight or fret in front of me lest I shatter.

I was plagued by wake-up-screaming nightmares so bad that I had to wear a mouth guard to keep from grinding my teeth into nubs as I slept. I couldn’t close my eyes without seeing it—that tentacle-mouth horror in the woods. I was convinced it had killed my grandfather and that it would soon return for me. Sometimes that sick panicky feeling would flood over me like it did that night and I’d be sure that nearby, lurking in a stand of dark trees, beyond the next car in a parking lot, behind the garage where I kept my bike, it was waiting.

My solution was to stop leaving the house. For weeks I refused even to venture into the driveway to collect the morning paper. I slept in a tangle of blankets on the laundry room floor, the only part of the house with no windows and also a door that locked from the inside. That’s where I spent the day of my grandfather’s funeral, sitting on the dryer with my laptop, trying to lose myself in online games.

I blamed myself for what happened.

If only I’d believed him

was my endless refrain. But I hadn’t believed him, and neither had anyone else, and now I knew how he must’ve felt because no one believed me, either. My version of events sounded perfectly rational until I was forced to say the words aloud, and then it sounded insane, particularly on the day I had to say them to the police officer who came to our house. I told him everything that had happened, even about the creature, as he sat nodding across the kitchen table, writing nothing in his spiral notebook. When I finished all he said was, “Great, thanks,” and then turned to my parents and asked if I’d “been to see anyone.” As if I wouldn’t know what that meant. I told him I had another statement to make and then held up my middle finger and walked out.

My parents yelled at me for the first time in weeks. It was kind of a relief, actually—that old sweet sound. I yelled some ugly things back. That they were glad Grandpa Portman was dead. That I was the only one who’d really loved him.

The cop and my parents talked in the driveway for a while, and then the cop drove off only to come back an hour later with a man who introduced himself as a sketch artist. He’d brought a big drawing pad and asked me to describe the creature again, and as I did he sketched it, stopping occasionally to ask for clarifications.

“How many eyes did it have?”

“Two.”

“Gotcha,” he said, as if monsters were a perfectly normal thing for a police sketch artist to be drawing.

As an attempt to placate me, it was pretty transparent. The biggest giveaway was when he tried to give me the finished sketch.

“Don’t you need this for your files or something?” I asked him.

He exchanged raised eyebrows with the cop. “Of course. What was I thinking?”

It was totally insulting.

Even my best and only friend Ricky didn’t believe me, and he’d been there. He swore up and down that he hadn’t seen any creature in the woods that night—even though I’d shined my flashlight right at it—which is just what he told the cops. He’d heard barking, though. We both had. So it wasn’t a huge surprise when the police concluded that a pack of feral dogs had killed my grandfather. Apparently they’d been spotted elsewhere and had taken bites out of a woman who’d been walking in Century Woods the week before. All at night, mind you. “Which is exactly when the creatures are hardest to see!” I said. But Ricky just shook his head and muttered something about me needing a “brain-shrinker.”