Miss Clare Remembers and Emily Davis (14 page)

Read Miss Clare Remembers and Emily Davis Online

Authors: Miss Read

'But what about Mrs Wardle?' asked Dolly.

'Rips up the sewing a bit,' said Emily laconically, jumping sideways into a fresh patch of snow which invited a few footprints.

'But I reckon they'll both be better than old Milk-and-Waterman.'

And Emily was right. On that first morning, as they sat together among their new school fellows, Dolly took stock of Fairacre School and began to feel the warmth of her surroundings thaw the bleakness which had numbed her for the past few weeks.

A massive fire roared behind the fireguard, and though it could not hope to warm completely a room so lofty and so full of cross draughts, yet it was a cheering sight on a cold January day. Mr Wardle, warming his trouser legs before it, proved to be a hearty boisterous man who welcomed the newcomers, and bade his schoolchildren do the same.

He was that rare thing, Dolly discovered later, a happy man. Blessed with boundless energy, superb physique, a lively wife and four children now out in the world, Mr Wardle enjoyed his little domain and liked to see those in it equally happy. His recipe was simple, and he told it to the children over and over again:

'Work hard. Do your best, and a bit more, and you'll get on.'

Sometimes he put his recipe into a different form and read them a homily about the sin of Sloth, which he considered the most vicious one among the seven.

'If you start getting lazy,' he would say, bouncing energetically up and down, 'you'll get liverish. And if you get liverish, you'll get sorry for yourself. And that's when the rot starts. Use your brain and your body to the utmost, and the Devil will know that he's beaten.'

He certainly set them all a fine example. His teaching was thorough, exact and lively. His spare time was taken up with gardening, walking his hounds for miles around the countryside, training the church choir, and adding to a magnificent collection of moths and butterflies. His authority was unquestioned, unlike that of poor Mr Waterman at Beech Green, and Dolly soon found herself responding to the vitality of this man who could kindle a spark in even the stolidest of his country scholars.

The children, perhaps because of Mr Wardle's example, seemed friendlier than those at Beech Green, and Emily and Dolly, who had secretly feared a little teasing and bullying, found no antagonism. Nor were any remarks passed about Dolly's black clothes, much to her relief. Although she did not know it until many years later, Mr Wardle had already warned his children about Dolly's loss and given them to understand that extra kindness would be expected of them, and good manners most certainly enforced, if his vigilant eye saw any shortcomings.

He was a man whose good heart and good head worked well together. Quick to recognise a child's vulnerability, he never descended to sarcasm and ridicule to gain his ends. Severe he could be, and when he was driven to caning them the cane fell heavily, but it rarely needed to be used. Work, exercise, fresh air and laughter kept his charges engrossed and healthy; and from Mr Wardle Dolly Clare learnt much of the ways of a good teacher.

About a week after their arrival, on January 22nd, 1901, Dolly and Emily sat with the rest of the big girls at one end of the main room, with needlework in their hands and Mrs Wardle's eye upon them.

It was called 'Fancywork' on the timetable, and each child had a square of fine canvas and skeins of red, blue, yellow and green wool on the desk in front of her. They were busy making samplers, using the various stitches which Mrs Wardle taught them. 'Fancywork' was a pleasant change from 'Plain Sewing' which involved hemming unbleached calico pillow slips with the strong possibility of seeing Mrs Wardle rip them undone at the end of the lesson.

The room was quiet. The boys at the other end were drawing a spray of laurel pinned against a white paper on the blackboard, and only the whisper of their pencils as they shaded the leaves and carefully left 'high-lights', broke the sleepy silence.

It was then that the muffled bell of St Patrick's next door began to ring, and Mr Wardle, looking perplexed, hurried out to investigate. When he returned a minute later, his rosy face was grave.

'I have very sad news,' he told his surprised listeners. 'Queen Victoria is dead.'

There was a shocked silence, broken only by the distant bell and the gasp from Mrs Wardle, as her hand flew to her heart.

'All stand!' commanded Mr Wardle. 'And we will say a short prayer for the Queen we have lost, and the King we have now to rule us.'

Afterwards, it seemed to the children, the grown-ups made too much of this event, but they were wrong. Their lives were short, and to them the Queen had always been a very old lady near to death. To their parents and grandparents, who had known and revered her for all their lives, this passing of a great Queen was the end of the world they had always known. National mourning was sincere, and tinged with the bewilderment of children who have lost the head of a family, long loved and irreplaceable.

Dolly never forgot Emily's words to her as they crept quietly from the playground that day to make their way homeward.

'Won't Frank be pleased,' said Emily, 'to have the Queen with him!'

It was exactly what Dolly herself had thought when Mr Wardle had broken the news, and the comfort of hearing it put into words was wonderfully heartening. Certainly the shock of this second death was considerably lessened by Emily's innocent philosophy, and the thought of Frank's gain mitigated their own sense of loss.

It was not the first time that Emily had been of comfort to Dolly by her ability to come to terms with the unknown. In the years to come, her Child-like simplicity and faith brought refreshment to them both.

Sixty or so years later, Miss Clare, half asleep in the shade of her plum tree, recalled that historic day, and its dark solemnity lit by Emily's touching confidence.

There certainly could be no greater contrast in the weather, thought Miss Clare, watching the heat waves shimmer across the sun-baked downs. In the border, the flaunting oriental poppies opened their petals so wide in the strong sunlight that they fell backwards to display the mop of black stamens at the centre. At the foot of the plant, Miss Clare's tortoise had pushed himself among the foliage, to escape from the June heat which even he could not endure.

She could hear the faraway voices of children at play, and guessed it must be about half past two, when Beech Green school had its afternoon break. Soon Emily would be with her again, as comforting and as hopeful as she had been on that bitter bleak day so long ago.

Miss Clare stretched her old stiff limbs in great contentment, revelling in the hot sunshine and the joy of Emily's coming. Looking back, she saw now that an age had closed on the day that Mr Wardle had called them to prayer, and she who since then had seen many reigns, could imagine the impact which Victoria's passing had made upon her parents' generation.

But for Dolly the twelve-year-old Child, that day had been chiefly a turning-point in her own happiness. She could see now, sixty years later, that several things had contributed to the sudden lightening of her misery. Mr Wardle's infectious vitality, new surroundings, work praised and encouraged, had all helped together to raise the child's spirits from the depths into which her brother's death had cast them. The natural buoyancy of youth and time's healing powers added their measure of restoration, but it was Emily's homely words which had really set her free at last. It was as though the Queen had taken Dolly's burden upon herself by entering into that unknown world where Frank already waited, and, fanciful though the idea seemed a lifetime later, yet it still seemed touching in the strength and hope it had given to a sad little girl who had needed comfort sorely.

'Ah! It's good to grow old,' said Miss Clare, contemplating that pitiful young figure across the years, 'and to know that nothing can ever hurt you very much again. There's a lot to be said for being seventy!'

And turning her face gratefully to the sun, she continued to wait, lapped in warmth and contentment, for the coming of Emily.

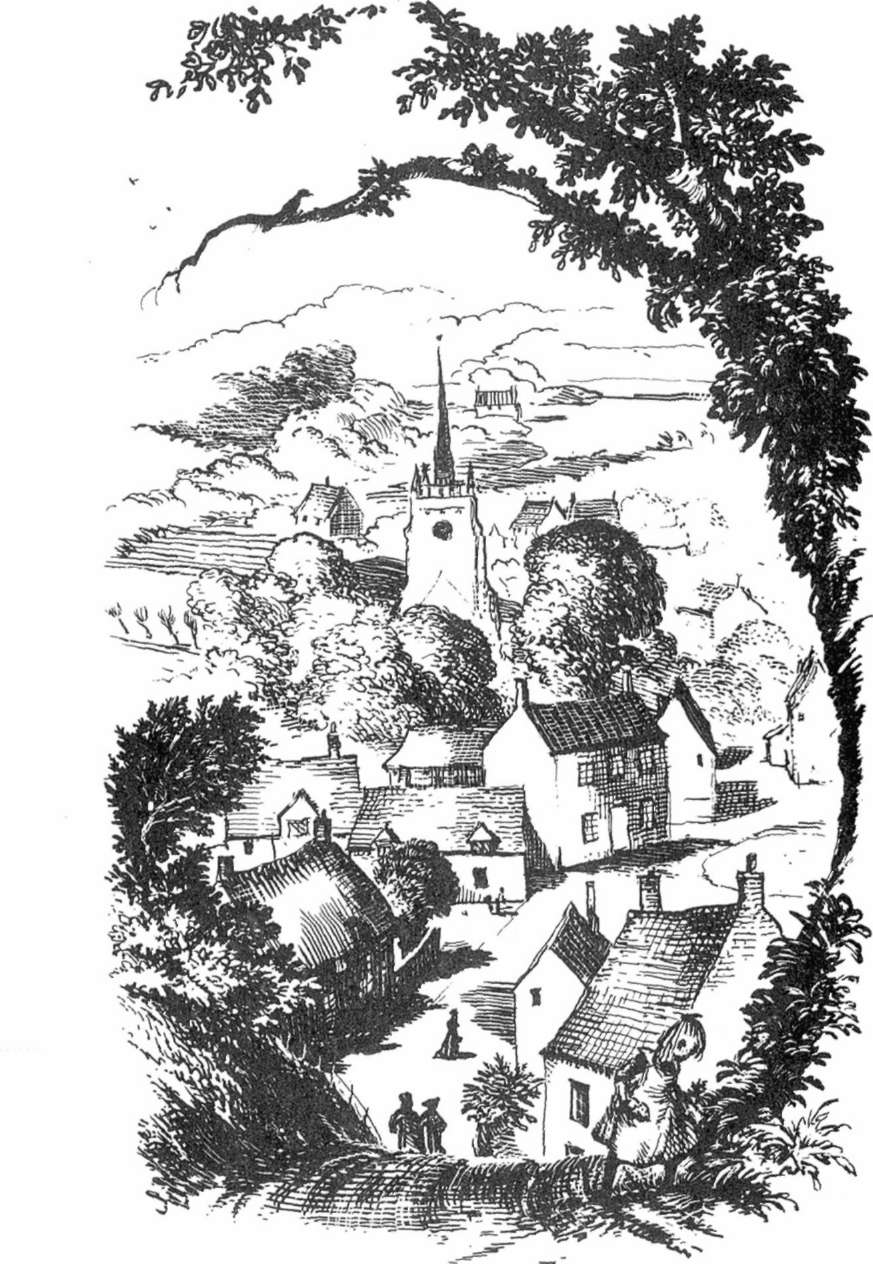

Fairacre

F

ROM

the first, Dolly Clare liked Fairacre. It was a compact and pretty village, grouped charmingly about its church, unlike Beech Green, which straggled along the road to Caxley. Some of the cottage roofs had been thatched by her own father, since they had come to live nearby, and still shone golden in the sunshine. More ancient roofs had weathered to a silvery grey, while others, more venerable still, sagged thinly across their supports and sprouted with green patches of moss and grass.

Not all the cottages were thatched. More than half were tiled with small tiles of a warm rosy brown which combined with the weathered brick to give a colourful appearance to the village. A few large houses, built in the reigns of Queen Anne and the early Georges, glowed with the same warm colour among their trees, and little Dolly Clare grew to love the vicarage, which could be seen plainly from the playground of Fairacre school, admiring its graceful fanlight over the front door, and the two great cedar trees which stood guard before it.

Fairacre, in those Edwardian days, was rich in fine trees, planted to give shelter, no doubt, from the roaring winds which swept the whaleback of the downs above it. Limes and horse-chestnuts shaded gardens, and clumps of magnificent elms sheltered the cattle and horses in the farm meadows. Close by the school, protecting both it and the school house, towered more elm trees, in which a thriving rookery clattered and cawed, and several of the neighbouring farms had leafy avenues leading to their houses. There was much more ivy about at that time. The dark glossy leaves muffled many a garden wall and outhouse, and added a richness to the general scene. When, in later life, Miss Clare looked at old photographs of the Fairacre she had known as a child, she realised how denuded of trees the village had become within her lifetime.

She and Emily loved it from the start. Their spirits rose as they turned the bend and approached the church and school. It was almost three miles to walk each morning, but the two little girls were quick to find lifts with obliging carters and tradesmen, and rarely had to walk both ways in the day. Dolly, who had been so frightened by the size of Bella on the day of the move from Caxley, now treated these great-hearted horses with affection and complete trust as she scrambled up from shaft or wheel hub to her high perch beside some good-natured driver who had taken pity on the two young travellers.

In all weathers, riding or walking, they traversed the familiar road. They looked out for the first wild flowers of spring, the pink wild roses that starred the summer hedges, and the bright beads of autumn berries. They watched the birds building nests, and could tell to a day when the eggs would hatch. They knew where a badger lived, and where a white owl would appear as they plodded home on a murky winter afternoon. Those three miles grew as familiar and as well-loved as the faces of their mothers. There was always something new, something beautiful, something strange, to find daily, and the two children learnt as much from their close scrutiny of banks and hedges as they did in the busy classroom at Fairacre school.

As Dolly and Emily neared the end of their schooldays, in the early part of Edward VII's reign, they found that one or the

other was frequently called upon to walk from Mr Wardle's room to the infants' room next door in order 'to give a hand', as Mr Wardle always put it, to the teacher in charge.

They were now called monitors, and with one or two other children of fourteen, undertook a number of daily jobs in the running of the school. Numbers thinned after the age of twelve, for those who could pass an examination in general proficiency were allowed to leave, and farmers were eager to employ these young boys now that labour was difficult to obtain. This meant that those over twelve who were left behind were often lucky enough to get closer attention from their headmaster. Mr Wardle looked upon Dolly and Emily as promising pupil teachers of the future, and gave them every opportunity of learning the rudiments of the job under his roof.