Mira's Diary (14 page)

Authors: Marissa Moss

I meant to go see Zola. Instead I went to Giverny with Mary to visit her friend, Claude Monet. I should have stayed in Paris and tried to talk to Zola, but since Mary was closing up her house for a week of thorough cleaning, I didn't really have a choice.

And actually, I was glad to go. Giverny was beautiful. The gardens were just like the paintings I'd seen of them in the Museum of Modern Art. Winding paths, graceful willows, ponds full of water lilies, croaking frogs, and humming dragonflies created a fairy-tale world. I could pretend to be a real artist, sketching for hours like everyone else.

Presiding over it all was Monet, with his long white beard, bushy white eyebrows, and friendly warmth. He was the opposite of Degas, sweet and gentle and always outside painting, even in the cold.

The house was full of guests. Besides me and Mary, a couple of writers (neither was Zola), a sculptor named Rodin, and Renoir, who I recognized. And of Monet's eight children, six still lived at home or were there for a visit. All the noise and laughter was the opposite of Degas's Spartan bachelor life. Knowing how he detested Monet and his easygoing good nature, I almost felt like a traitor being there, but it was so nice to spend hours drawing, part of a warm circle of friends and family.

I missed my own family and the circle we'd had. Where was Mom anyway? What were Malcolm and Dad doing right now? I imagined them frozen by the Eiffel Tower, waiting for me to return, the way they had on the walkway of Notre Dame. For me, days had passed. For them, maybe not even a minute, certainly not long enough to miss me. For them it was hot summer; for me it was chilly autumn.

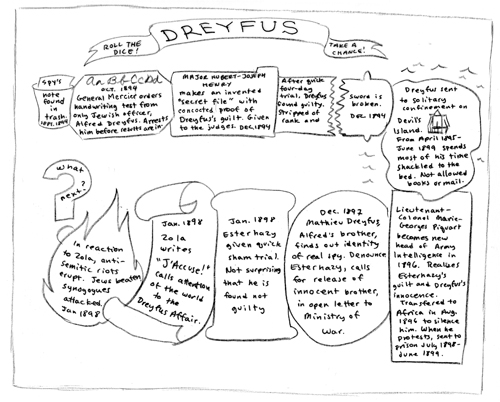

In late afternoons when the light was too dull to paint by, everyone gathered in the large front room in front of the fireplace, sipping tea and eating sweets. There'd been some gossip about Degas, how lonely he was in his self-imposed anti-Dreyfus bubble, but most of the talk was about the Dreyfus case itself. There were so many twists and turns that it was like an elaborate murder mystery.

“Look at today's newspaper,” Monet said last night. “Zola has entered the discussion. He wrote an essay, not so much about Dreyfus as about Senator Scheurer-Kestner who has seen the evidence of Esterházy's guilt and denounced him as the true traitor.”

“May I see?” I tried not to snatch the paper, but reached for it politely. Even with my limited French, I could tell it was expressive writing, not a dry list of facts, but a call to arms. Zola didn't say much, but he ended with: “The truth is on the march and nothing shall stop it.” I hoped he was right.

“Will this make a difference?” I asked. This was what Mom had wanted, what she'd worked so hard for, but was it enough? And it was exactly what Dad and Malcolm said needed to happenâthe press had to tell the truth so the people would know what the military had done. But would people care?

Monet shrugged. “If the truth is truly on the march, it will. Me, I put my faith in my garden, my paints, and my brushes. To trust the government to do the right thing when it would be such an embarrassing scandal? I have my doubts.”

“I wish the whole ugly affair were over,” Renoir said. “And Degas could let go of all this, admit he's wrong once the military has admitted they were wrong, and then we could all be friends again.”

“Degas holds grudges,” Mary said, nibbling at a tart. “I wouldn't count on it. He can be the most loyal, generous friend, but stronger than that is his stubbornness.”

“Good for him!” Rodin bellowed. He was a big bear of a man with hands as big as dinner plates and a booming voice to match. “The man has the courage of his convictions. He stands up for what he believes in. I may not share his beliefs, but I share his backbone! There are too many whiners with small, petty concerns bringing this country down.

“I told you about the criticism the boorish mayor of Calais had about my sculpture of the burghers. Here I am, creating a monumental group of men surrendering the keys to the cityâsurrendering, I sayâand the mayor snipes that I've made their faces too anguished, their attitudes too dejected. The moron wants stoic heroes drained of blood on display, I tell you!”

“Stop complaining, Rodin.” Monet smiled. “You love the controversy. Admit it. Otherwise you wouldn't be making that large portrait of Balzac nude. You know how tongues will wag!”

“It's only the study, the model, that's nude. He'll be wearing an impressive cloak in the finished piece.”

“But he'll be naked under that, and everyone will know!” Renoir chuckled.

I didn't know who Balzac was, though the name alone sounded heavy with importance. Funny, I thought, Renoir, Degas, Monet, they all sounded light and bubbly, full of sun and warmth. But Rodin and Balzac sounded heavy and hollow. And Dreyfus, Dreyfus sounded like trouble, like a difficult problem I had to solve.

Back in Paris on my way home to Mary's, I recognized Degas on the other side of the street, walking aimlessly. He bumped into a man who obviously knew him, but Degas squinted at him as if he couldn't see clearly.

“It's my eyes. You must forgive me, I can't see a thing,” he said.

“I'm so sorry to hear that,” the friend said.

“I'm used to it.” Degas waved away any sympathy. He pulled out his pocket watch, checked the time, and said he had to be going or he would be late.

The other man believed the little charade but I almost laughed. How bad could Degas's eyes be if he could see the small watch face clearly? I couldn't help still liking him. Seeing him alone on the street after spending time with Monet and his crowded household, I felt sorry for Degas's narrow-mindedness, his aristocratic blinders. He was still a great painter and a kind, gentle soul at heart, although he was wrapped in a gruff exterior, armored with stubbornness.

Besides, patriotism cloaks a multitude of sins. He wasn't the first or the last to say, “My country, right or wrong,” even when that country was obviously, clearly, blatantly wrong. And Rodin had a point. It wasn't as if Degas was taking the easy way out. He was miserable in his loneliness; I was sure of it. But he had to follow what he believed. There was something admirable about that.

But of course, being Jewish and automatically suspicious to him now, I couldn't say any of this to Degas. And that wasn't my job anymore. I figured the best place to start was Zola.

Mary Cassatt didn't know him well, but she found out where he lived, not far from the Gare Saint-Lazare. I had it all planned out. I would tell him I was an American journalist and I wanted to interview him about his opinion on the Dreyfus case. If I told him how important his words were, what a difference he was making in international circles, maybe he'd write more, do something to directly support Dreyfus and get the truth out there.

At least that was my plan. Plan B was that maybe he'd tell me where to find Mom. Because I was sure he knew her.

Zola turned out to be absolutely gallant and charming. His cool gray eyes shone with good humor and wit. He was the opposite of big, gruff Rodinâsmall and neat with elegant fingers. His rooms were like him, orderly and clean, each Chinese vase and glass paperweight clearly in its proper place.

He was so welcoming that I just plunged in and asked him if he could think of a way to support Dreyfus and convince the public of the enormous fraud the military was committing.

“I already wrote an article on the whole sorry affair.” Zola gestured to a copy of the article on the table between us.

“Yes, but it's not enough. You wrote about the senator and his stand for the truth. You need to do more than thatâto spell out each way the army framed Dreyfus. You need to be dramatic to change public opinion.”

“I really think that kind of impassioned argument is best left for the young, someone like you, for example.”

“But you have a reputation as a great man of letters. Your opinion matters! Mine is worth nothing. And you wrote that novel criticizing the army before. You have a reputation of not being beholden to anyone.”

Zola sighed. “I have a lot more to lose now than I did then.”

“But aren't you as passionate about the truth as ever?” I pressed.

“I admit I have been talking to senators, to officers in the army, and what I'm learning is enough to goad even a silent stone into screaming the truth.”

“Then you'll do it?”

“I didn't say that.” Zola shook his head. “Someone younger really should. Someone who isn't a member of the Legion of Honor. Someone who has less to lose.”

I hated to think that I would be less idealistic when I got older, that I'd care less about horrible injustice. I promised myself I wouldn't, that I'd always care about the truth, even if it came with a high cost. Maybe I just had to make Zola realize how awful it all really was.

A man was chained to a bed in a stifling prison, far from his family, not allowed visits or letters or anything that would give him hope. And meanwhile, the real traitor was free to go where he wanted. And the military not only knew he was the actual spy, but they were shielding him from any suspicion. How could anybody with a shred of moral sense stay silent if they knew that? And suddenly I understood that was what Zola had to write about. That was the important truth that needed to be told.

“You know that the army has been protecting Esterházy, the real spy?” I asked, dropping my little bomb.

“Ah, that's something I didn't know!” Zola's eyes lit up. “The corruption goes that far? Do you have names you can give me? What evidence do you have?” He leaned forward eagerly, grabbing a block of paper and fountain pen from his desk. Had I really convinced him?

I described the meeting with Esterházy, but the only name I knew for sure was Henry's.

“Describe the other two men in more detail, the ones wearing the disguises,” urged Zola. “I may be able to recognize them.”

“Maybe it would be better if show you the sketches I made of them,” I suggested. This wasn't about art, but identity, so I tried not to be embarrassed by my unskilled drawing.

“Yes, please do!” Zola leaned forward eagerly as I handed him my sketchbook.

“I don't believe it!” he gasped, recognizing one of the men instantly. “Your bearded man is Major Du Paty, the scoundrel! He's the one who insisted Dreyfus's handwriting matched the treacherous note in the first place. He never cared about finding the real culprit. He was so eager to tar a Jew.”

“And the other man?”

Zola examined my sketch again. “That looks very much like Félix Gribelin, the military archivist who was involved in Dreyfus's arrest. Both of these men need Dreyfus to stay guilty.”

“So much that they need to protect the real traitor?” I asked. “I can't believe that instead of going after the real spy, the actual danger, they'd rather ruin an innocent man's life. It seems so stupid!”

Zola nodded. “I knew that the conspiracy to convict Dreyfus went to the highest levels of the army, all who knew, absolutely knew, that Dreyfus was innocent, but as you say, they preferred to send an innocent man to Devil's Island rather than admit their ineptitude at first and their responsibility for a cover-up later. But now you're saying it's even worse than thatâthey not only knew of Esterházy's guilt, they are protecting him!”

“All because Dreyfus was Jewish?” I asked, as if I didn't already know it.

“Yes.” Zola sighed. “I thought more of my country, but I was wrong. I wonder if such a thing could have happened in England or in your own America.”

It probably could. We weren't such a nice country either. How were we treating African Americans in the 1890s? Or Native Americans? Nobody said anything about that. No important, exciting news stories declaring that justice was on the march. That wouldn't happen until the 1960s!

“It's horrible how much hatred and prejudice can blind people to the truth.” Zola went on. “They see what they want to see, even when doing so puts their own interests at risk.”

“All that because of a different religion.” I felt sick to my stomach.

“Well, more than a religion. It's a racial question, you know. The âevil' Jewish race has been a scapegoat for thousands of years. It's easier to hate the other than to tolerate it.”

I hadn't thought of Judaism as a racial thing. Sure, it was more than a religion. I'd always considered it a cultural identity, but it was weird to think I'd be judged as a distinctive race. Strange to think that even in the multicultural twenty-first century, racial differences were still used to stereotype people. I wondered what truths we weren't seeing because of racial blinders, what mistakes were being made. Were we any better that the nineteenth-century French?

It was getting late, but I still had to ask about Mom. “This might sound odd,” I began, “but I'm looking for a fellow American, an older woman, who is also following this story. Perhaps you know her?”

“Do you mean Serena Goldin?”

Mom! Yes, he knew Mom!

“I saw Madame Goldin just last week. She helped me with the material for my article. I don't know how she got it, but she had some powerful evidence. As you have. I could not write as strong an argument without the two of you, so I'm truly grateful.”

I blushed. Was he definitely going to write the article then? Had I really helped him? And, most importantly, where was Mom now? “Do you know where I could find her?” I asked.

“We were actually supposed to meet today, but she never came. You can try her at her hotel. She stays at L'Américaine on the Boulevard Richelieu.”

I tried to stay calm as I thanked Zola and headed down the stairs to the front door. I walked out into the dusk, not sure which way to go. The gaslights were just being lit and the street was full of shadows. But one shadow, there by the side of Zola's house, looked creepily familiar. It was Madame Lefoutre! She was talking to a chimney sweep. I flattened myself to the wall, hoping she hadn't seen me.

The chimney sweep nodded and left. Madame walked in front of me and kept going. This was my chance to see what she was up to. I tried to follow her as discreetly as I could, but she walked quickly and I had to jog sometimes to keep up. Movies make tailing someone look easy, but really it was hard. Where there were a lot of people around, it was easier, but there were empty stretches where all Madame had to do was turn around and she'd see me.

She'd walked about twenty minutes when she did exactly that. She turned to face me, and I swear her eyes glowed a demonic red. Her mouth twisted in an ugly grimace, scarring her perfect face. Her eyebrows swooped down into a menacing glare.

“You!” she hissed.

I stood there frozen in terror. I didn't know what to say or do.

She took a step toward me. I stepped back. This time I didn't have a parasol to whack her with. I looked around for any kind of weapon; even a stone would do. But there wasn't anything. Unless I hit her over the head with my sketchbook.

“You've ruined everything!” she screeched. “But it's not over yet, not by a long shot.” She turned, stiff skirts swishing, and strode away. I started following her again, not bothering to be careful now that she knew I was there.

“Good thing time is on my side!” she yelled. “Now go home and stop meddling!” She reached out to a bronze fountain.

“What do you mean?” I yelled. But it was too late. She was gone in a crackling of light.