Mind and Emotions (6 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

Nadia avoided feeling angry at her emotionally distant parents and her verbally abusive boyfriend by dulling her feelings with alcohol and drugs. She had a Paxil with breakfast, beer with lunch, wine with dinner, and brandy and an Excedrin PM before bed—just enough to take the edge off rage and dampen her impulse to lash out at those around her. In the short term she got through her days, albeit in a blur, but as time went on she was becoming more dependent on alcohol and drugs.

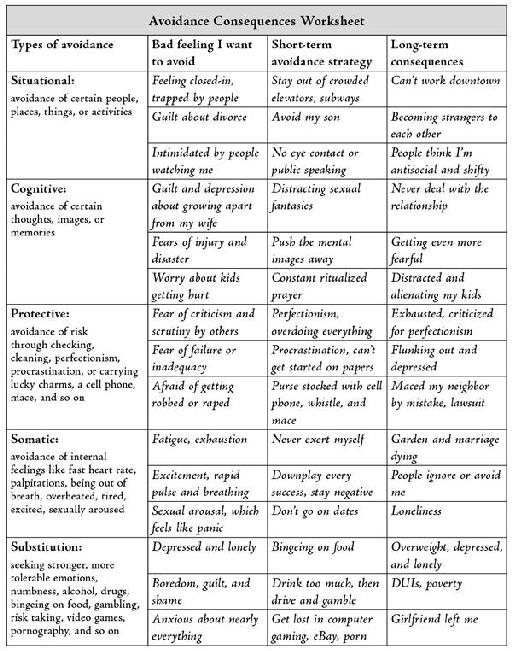

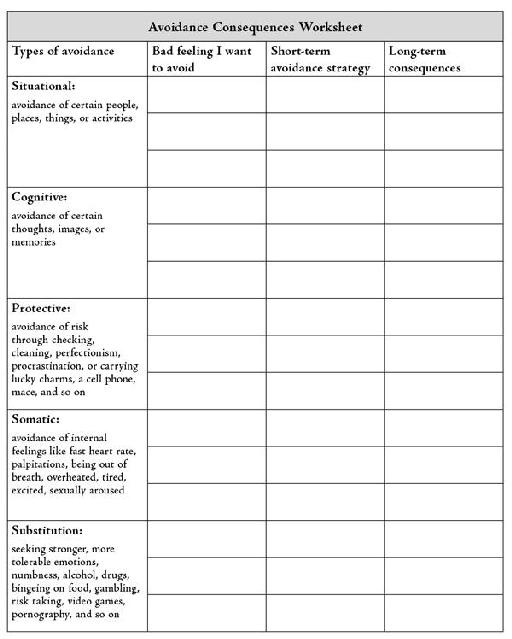

Assessing Your Avoidance Strategies

Using the following worksheet, list the difficult feelings you try to avoid, your short-term avoidance strategies, and the long-term consequences in your life. Do this for each of the types of avoidance that you employ on a regular basis. Below, we’ve provided a sample worksheet that combines responses from several people with typical avoidance experiences.

Exposure and Its Benefits

In the jargon of psychology,

exposure

is the opposite of, and the solution for, avoidance. Exposure means that you stop avoiding painful feelings and start to actually experience the things that make you feel afraid, depressed, guilty, ashamed, or angry. “Exposure” is a scary word. It sounds like walking into a typhoid ward, being stuck out in the cold or on a steep mountainside, or standing in the middle of a battlefield.

In everyday language, better terms for exposure might be “living fully” or “participating in your own life,” because, in the long run, that’s what it feels like to get out of the vicious cycle of short-term avoidance and long-term disaster. That’s what it feels like to begin accepting your feelings, coping with the inevitable ups and downs of emotion, and moving forward in life on your own terms.

The benefits of exposure are threefold: First, you realize that although painful feelings are inevitable, they won’t kill you and they don’t last. Second, successfully coping with a difficult feeling sometimes gives you a sense of empowerment and a boost in self-esteem that makes exposure easier the next time. Third, and most importantly, you know that you’re showing up and participating in your own life and living according to your true values, not according to your fears and doubts.

Chapter 4

Values in Action

What Is It?

Your values are your chosen directions in life. They’re what you want your life to be about. Your values give your life meaning, vitality, power, inspiration, and motivation. They help activate you to break out of life-restricting patterns caused by anxiety and shame, or the torpor and withdrawal that fuel depression. In this chapter you’ll consider key areas of your life, consider which are most important to you, and uncover what you care about—your core values—in each area that’s important to you. You’ll also describe the barriers you encounter in each area and make a plan for committed action in service of your core values.

Clarifying and acting on your core values is a key component of acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes, Strosahl, Wilson 1999).

Why Do It?

Putting your values into action will give your life meaning and direction. Values clarification directly addresses the transdiagnostic factor short-term focus, the maladaptive coping strategy that allows the painful emotions you feel in the moment to prevent you from doing what you really want to do in the longer term. You focus on avoiding pain in the short term, even though this has huge costs later in terms of quality of life.

For example, fear of a panic attack might keep you from attending a family reunion, even though you want to be with your family because you love them and you value keeping in touch with your roots. Likewise, it might stop you from accepting an invitation to go out on a date with someone interesting you recently met, even if you want to go on the date because you value companionship and intimacy. This short-term focus on avoiding anxiety (or any other painful experience) constricts your life over time. Getting clear about your core values and making a commitment to act according to your values make it easier to get beyond short-term emotional barriers.

What to Do

Acceptance and commitment therapy makes a clear distinction between values and goals. Values are a direction, and goals are specific destinations or waypoints as you travel in the direction of a given value. Values are a process, whereas goals are a product. For example, honesty is a value, whereas returning something you stole is a goal. Values tend to be expressed as basic, intrinsic, abstract principles, like love, truth, trust, or fidelity. Values aren’t needs, desires, or preferences, such as food, sex, or classical music. Some values, such as creativity, are associated mostly with your own welfare. Other values, like generosity, are directed more toward the welfare of others.

Identifying Your Core Values

The worksheet that follows will help you determine which areas of your life are most important to you and what you care about in those areas. The worksheet is organized into ten domains—common areas of life in which people typically hold strong values. Some of the domains will be very important to you, whereas others won’t be so meaningful. And there may be one or two others you want to add. To help you sort out these different areas of your life, here are short descriptions of the domains covered on the following worksheet. As you read through these descriptions, spend some time thinking about each and considering how important it is to you:

- Intimate relationships.

This domain is about your relationship with your significant other: spouse, partner, lover, boyfriend, or girlfriend. If you aren’t with anyone right now, you can still work on this domain in terms of your ideal relationship with some future person. Typical terms for values in the domain of intimate relationships are “love,” “openness,” and “fidelity.” - Parenting.

What does being a mother or father mean to you? You can answer this question even if you don’t have children. In the domain of parenting, many people use terms like “protecting,” “teaching,” and “love.” - Education and learning.

Whether or not you’re in school, there are many times in your life when you’re learning something new. Working through this book is a good example. Terms for values related to learning might be “truth,” “wisdom,” and “skill.” - Friends and social life.

Who is your closest friend? How many good friends do you have? What would you like to be doing with your friends, or how many new friends would you have, if your fear, sadness, anger, or shame didn’t get in the way? Values that underlie friendship might be expressed with words like “loyalty,” “trust,” and “love.” - Physical self-care and health.

What kinds of changes would you like to see in your life in terms of diet, exercise, and preventive measures? In the domain of the physical, values are expressed with words like “strength,” “vitality,” and “health.” - Family of origin.

Consider the importance of your relationships with your father, mother, and siblings. How would you like these relationships to be? Many people speak of their values related to their family of origin with terms like “love,” “respect,” and “acceptance.” - Spirituality.

Are you aware of or connected to something larger than yourself, something that transcends what you can see and hear and touch? Spirituality is wide-open. It can take the form of meditation, participation in organized religion, walks in the woods, or whatever works for you. In this area, people’s values usually involve having a certain relationship to God, a higher power, chi (energy), or the universe. - Community life and citizenship.

Do your negative emotions keep you from charitable work, serving your community, or political action of some kind? Values in the public arena are often expressed with words like “justice,” “responsibility,” and “charity.” - Recreation and leisure.

If you could get past your anger, sadness, guilt, or anxiety, how would you spend your leisure time? How would you recharge your batteries and reconnect with family and friends in fun and games? Recreation values are expressed with terms like “fun,” “creativity,” and “passion.” - Work and career.

Most people spend a large chunk of their lives at work. What would you like to accomplish at work? What kind of contribution would you like to make? What do you want to stand for in your workplace? What intentions did you have when you started working that you still haven’t put into action? Typical terms for values related to work and career are “right livelihood,” “excellence,” and “stewardship.”

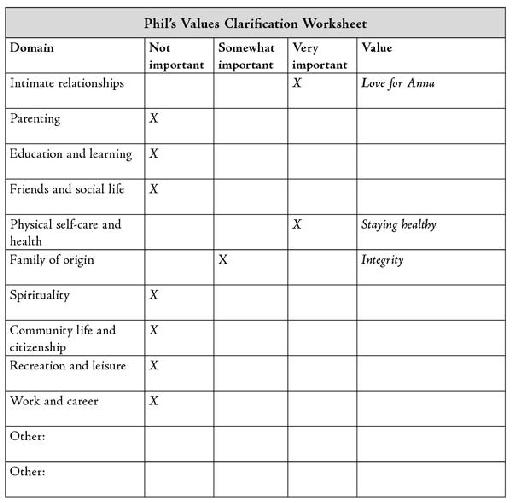

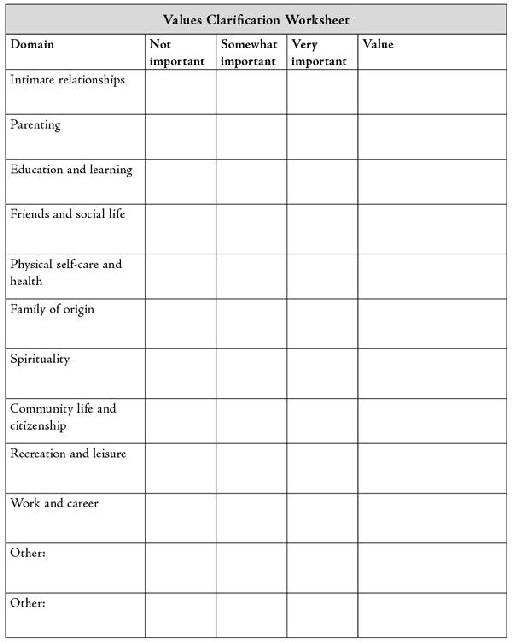

Based on these descriptions, complete the following Values Clarification Worksheet. (Because it’s worthwhile to reassess your values from time to time, you may want to make a copy and leave the version in the book blank for future use.) Start by indicating the relative importance of each domain for you, placing an X under “Not important,” “Somewhat important,” or “Very important,” as appropriate. You may want to add your own domains at the bottom of the worksheet.

Next, for the domains that you marked “Somewhat important” or “Very important,” write just a few words that sum up your core value. A blank worksheet follows the sample version.

The worksheet below was filled out by Phil, a fifty-four-year-old technical writer for a software company, who’s been feeling depressed, anxious, and guilty. Phil has been married to Anna for fifteen years, and they’ve both put on weight and aren’t feeling very interested in each other sexually or otherwise these days. Phil’s dad died two years ago and Phil was the executor of his dad’s will. He borrowed $4,000 from the estate without telling his two brothers and hasn’t paid it back, and he feels guilty about it. On top of all this, he was recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, but he hasn’t managed to get on top of checking his blood sugar and changing his diet.

Keeping a Values in Action Log