Millions Like Us (56 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Women’s memoirs of the immediate post-war period demonstrate very clearly that feelings of isolation, nostalgia and apprehensiveness had begun to replace end-of-war euphoria. The urgent work that had given their lives value and meaning had been removed; with it had been extinguished what Nella Last described as ‘

the white flame’

driving all their efforts: the desire for peace. But now that it had come, was that peace – with all its tantalising, indefinable promises of security and contentment – just a mirage?

A wintry light filtered through the uncurtained panes of the Cadogan Street bedsit.

Ex-Flight Officer Wyndham

woke to the sound of her landlord’s sewing machine whirring gently and the distant thrum of London traffic. Shivering, she climbed out of bed and lit the gas fire, but the bathroom down the passage was freezing. Crouching on the hearth, she removed the wire pipe cleaners that served as crimpers in her hair and styled her dark curls, before repairing the ravages with Max Factor and Yardley’s Cherry. ‘Now I was ready to face the world.’

After four years as a WAAF, Joan was completely free. During her last few months in the service the array of choices before her seemed like an irresistible menu for the future. She might become a teacher;

or maybe let her legs get hairy, grow an earnest fringe and go to Oxford. Another scenario was to get a job selling clothes at Jaeger. If that failed, she and her girlfriend Oscar planned to start up a hamburger café. Then there was her thrilling new boyfriend, Kit Latimer; with him, finally, she had experienced ‘the big O’, and from then on their sex life had gone from strength to strength. Maybe they would get married and have babies (but what about the fact that he was penniless?). Life seemed to spread out its delicacies before her: countries she’d never seen, books she’d never read, people she’d never met, new loves. She wanted to devour everything, ‘with such an acute and all-consuming appetite that it gives me a dry mouth, a tingling tongue and a pain in the side of my head’.

Two months later she was living in a room in Chelsea that cost £2 a week, with a battered gramophone, a stack of Fats Waller records, a dilapidated divan and her WAAF uniform dyed forest green. She had her £60 service gratuity, which would pay for the room till the following summer, but nothing to live on. Her only saleable skills were top-speed radar-plotting and commanding parade-ground drill: ‘not much bloody use to me now’.

What to do with my day, jobless and faced by the awesome prospect of endless leave? I was beginning to realise that now I was no longer in the WAAF I would have to recreate my world from scratch every morning.

I hadn’t realised I was going to feel so lonely, with no one to laugh or gossip with, no focus to my life.

Money was the first priority. Joan decided against breaking into her £60, which was earmarked for the rent. She piled her old ballet books into a suitcase and set off for the Charing Cross Road second-hand bookshops; a couple of hours later, with twelve crisp pound notes carefully hidden away, Joan was on her way to the White City dog-racing track. There

was

one useful skill she had acquired during her years in the Air Force …

Helen Vlasto was twenty-five in 1945; Joan Wyndham was twenty-two. For them, and many thousands like them, their time doing war work had moulded and fashioned the people they now were. For four or five years in many cases, their lives had had a structure imposed by authority. It was constantly impressed upon them that they were wanted and needed.

Wren telegraphist

Anne Glynn-Jones recalled

‘the feeling that you were doing a real job, a job that mattered, that took quite a bit of skill – I loved it’.

Flo Mahony thrived

off it. ‘Some people didn’t like regimentation, but I did – absolutely loved it. You just felt all the time that you were doing a worthwhile job.’ For Flo, her WAAF friendships, and the sense of purpose the service gave her, would remain for ever.

And now, with peace, came the dismantling of the entire apparatus that had given meaning to these women’s lives. ‘Every week now people were leaving.

An edifice seemed

to be crumbling,’ remembered WAAF Pip Beck.

Stoker Wren Rozelle Raynes

spent the final days before Christmas 1945 in a state of nightmarish torment. For two and a half years her life had consisted of ‘a happy whirl of nautical activities … unimagined maritime bliss’. Now, at the age of nineteen, her world was being pulled from beneath her. She spring-cleaned her office, went for a demob medical inspection, attended her last pay-muster and packed. At midday on 22 December 1945 she was summoned before the commander to say goodbye:

I had managed to get through the previous two days in a numbed sort of misery, but suddenly I felt I could bear it no longer … I … lost all control, and bursting into floods of tears ran blindly from his office.

Wren Rozelle Raynes sketched herself setting out to seek her post-war fortune far from her beloved Portsmouth.

Running on Empty

But Jean McFadyen

was only too happy to find, in the autumn of 1945, that her services were no longer required. After three years of sweat, toil, blisters, backache, chafing, chilblains and freezing Aberdeenshire winters in the Timber Corps anything seemed preferable. With Jim recovered from his ordeal in the prison camp, they decided to get married at the earliest opportunity:

There was no question of a big church wedding or anything like that – it couldn’t be done in the time allotted, and we couldn’t have spent the money on it. Plus, everything was still on the ration.

We got married Christmas Eve 1945. It wasn’t a white wedding – and I didn’t have a long dress either. But it was a happy day, and we even had a dance! Jim had put quite a bit of weight back on by then; he looked much more like himself.

He was given his old job back – it was in a biscuit factory. At that time whatever a man was working at before he went away to the army, they had to keep that employment open. I didn’t work – it wasn’t thought seemly for married women, and men didn’t like it if they did.

But of course we had no house. We got married without even giving a thought to where we were going to live or anything like that. We lived with Jim’s mother and father. And I kept talking to Jim about getting a job, but it was ‘Oh, no, no, no – I’ll keep my wife.’ He just didn’t want me to. Very,

very

few of the men did at that time. I’d proved I

could

work, but ‘No’. And – two women in a house … and it was not a big house either … And though I got on very well with his mother – we shared the housework – there were stresses. And I used to scan the paper every night for the hope that there might be somebody with a room to let somewhere so that we could move out and get a place of our own, but nothing ever appeared.

In March 1945 the Coalition White Paper had estimated that, in order for every family unit that wanted a home to have one, 750,000 new houses would have to be built. Until they were, a great many young men and women like Jean and Jim had no choice but to start their married lives crammed in with their in-laws. Domestic life became ever more stressful as a result. Meanwhile, there was nothing to do but pore over the small ads and importune the Council.

When Joan and Les Kelsall

tried to set up home in Coventry their future looked very bleak. A total of nearly 4,500 homes had been destroyed in the November 1940 and April 1941 raids on that city. It didn’t help that Joan, during a wait of over three years for her absent fiancé, had carved out an independent existence for herself. War had brought her a responsible WAAF posting in the Royal Observer Corps and a promising new romance which might have led to marriage – had she not already had Les’s ring on her finger. In 1944, when Les finally came home, they married straight away. Joan became pregnant early in 1945 and was dismissed from the WAAFs – ‘they more or less sacked me’ – and their daughter Sue was born in November 1945. There was no question of being able to find a home of their own; instead, they lived with Joan’s widowed father:

You just couldn’t get a house, and my brother lived at home, so I had three men – and a baby – to look after and cook for, and no mum. It got pretty tense and difficult sometimes, because they didn’t all get on, and I was sort of piggy-in-the-middle.

Les himself had spent three years as a naval signalman. While docked in Malta his ship had been the target of a Luftwaffe raid; there were terrible casualties, and Les was lucky to get away with shrapnel wounds in his leg.

I think the war affected a lot of men and they soon flared up when things weren’t right – a lot of it was due to what they’d gone through. Les said, ‘I’ve seen enough dead bodies, I don’t want to see any more.’ And I felt outnumbered. I’d been on my own and grown up; I’d turned twenty-one. And I didn’t like having to give up the independence that I’d had, having to consider other people besides myself. And so we argued.

And my father always seemed to be telling me what to do if the baby cried … and that caused problems.

Well then we moved in with Les’s parents and lived with them until my daughter was two … and then we had a

dreadful

row with his parents. And Les said ‘Right, I’m going to get us somewhere to live.’ And his father said, ‘

You’ll

never get anywhere,’ he said. ‘Your head’s too big,’ he said. ‘They wouldn’t get a hat to fit you!’ I’ve never forgotten that!

So Les said to me, ‘Get Sue ready,’ he said, ‘you’re coming down to the Council with me.’ So we went down to the Council, and, oh dear, I was that embarrassed, there he was banging the counter … He said ‘I’ve served this country,’ he said, ‘and there’s

nothing

for us to come back to’. And in the end, we ended up with a prefab.

We lived there for seven years. When we moved in all we’d got was a cot, a pram, a bed and two hard chairs and a couple of cushions. It felt like a proper bungalow – the rooms were quite big. And it was modern – we weren’t used to having a tank full of hot water! And it had a well-equipped kitchen, bathroom, flushing toilet and a garden. And it was a lovely home. Everybody knew everybody else, and we were all more or less the same age – with children too – and if your children were ill there was always somebody knocking on the door to see if you wanted something from the shops … I really loved it. I cried when we left.

For many women like this, the yearning for a home was more than the simple wish for privacy. Home was

who they were

, their creative power-base, a projection of their very identity. ‘

Four walls and a roof

is the height of my ambition,’ said one Mass Observation respondent.

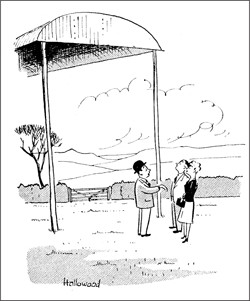

‘Well, were you or were you NOT the young couple advertising for a roof to put over their heads?’ A roof

and

four walls in 1946? Dream on …

The Kelsalls were lucky. Many people who had become unhappily dependent on relatives or friends for accommodation jumped

on

the squatting bandwagon

that started to gather pace in the summer of 1946. The authorities took a compassionate view, turning a blind eye to the trespasses of families who set up home with chemical toilets and orange boxes in disused service camps across the country. They were somewhat less benevolent in the case of a mass squat organised by the British Communist Party, which persuaded dozens of families to take over a block of unoccupied luxury flats in Kensington.

The journalist Mollie Panter-Downes

managed to gain entry and gave a sympathetic account of the squatters’ predicament. One couple had come from sharing just two rooms with three other couples. It was eighteen months since the man had been demobbed, and in all that time he hadn’t been able to sleep with his wife, because the four husbands all slept together in one room, the four wives and all their kids in the other.