Millions Like Us (37 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

‘I had a simply wonderful leave – my heart was broken four times.’ Away from watchful parental eyes, many young women revelled in the opportunity for off-duty romance.

There were ominous thuds as Dylan hurled himself against the panelling. Thump went Dylan! Crump went the bombs! …

At last I heard Ruthven’s voice firmly remonstrating, and finally the sounds of a heavy body being dragged reluctantly away.

I curled myself up under my greatcoat and slept like the dead.

*

Elizabeth Jane Howard

was another hugely talented writer who confesses that her war was largely defined by men and sex. ‘I do think people went to bed with each other much more easily,’ she says today, ‘very largely because it might be the last thing they did. It’s probably Nature’s way of preserving the human race.’ Old age has given Jane Howard a kind of queenly assurance, as well as an unembarrassed honesty about her own youthful faults. In her autobiography

Slipstream

(2002) Jane Howard describes herself as ‘essentially immature … I’d succeeded in nothing …’ She tells how she was turned down by the Wrens (who considered her under-qualified), and describes her unhappy marriage with Peter Scott. But in 1942 Jane became pregnant. As an important naval officer, Scott was allowed to have his wife billeted in a comfortable hotel close to his base, but he was out all day. ‘I was homesick, and I didn’t know what the hell to do with myself.’ Pregnancy exempted her from war work. ‘I read, I ran out of books, and I went for walks … I felt terribly sick. And the only thing to eat at this ghastly hotel was lobster. You try having lobster twice a day for three months when you’re feeling rather queasy.’ That winter she moved back to London. On 2 February 1943 – the day the Germans surrendered at Stalingrad – her daughter was prematurely born during an air raid.

But after a traumatic birth, Jane lacked maternal feelings for baby Nicola, who screamed, wouldn’t feed and only compounded her sense of inadequacy. That summer she fell in love with Wayland Scott, her husband’s brother. ‘The first time he kissed me I discovered what physical desire meant … I was his first love as in a sense he was mine.’ They cemented the guilt by sleeping together, then owning up to Peter. There was a terrible row, and Jane was carted off to stagnate at his naval base in Holyhead. But it was only a matter of time before the vacuum in her life was refilled. Threatened by boredom in Holyhead, she decided to put on a production of

The Importance of Being Earnest

with the navy, with Philip Lee, a handsome blond officer, playing Algernon to her Gwendoline. One winter afternoon they climbed Holyhead Mountain and made love among the crags. The affair continued after her return to London, where they borrowed a painter friend’s studio for delicious, secret assignations. ‘I don’t think Pete ever knew about it.’

*

Meanwhile, Phyllis Noble

still felt uncommitted, despite the physical bond that now held her to her lover. Her insistent sexual desire for Andrew seemed to point in the direction of commitment. Her parents liked him; her choice of boyfriend, if not her illicit sex life, had their blessing. But the war pushed in the opposite direction. Nursing, perhaps, would give her the chance to ‘do her bit’ while experiencing

foreign parts. But in late 1942 the government was drawing ever more women into the conscription net, and, finally, Phyllis heard that she was to be released from the bank. However, conscription took little account of preferences; you had to go where you were needed, and the fear that she might be called up for the dreaded ATS made Phyllis consider, briefly, whether it would be best to avoid the whole thing by just going ahead and getting married. ‘I knew Andrew was willing, and sometimes during our best moments together I thought I might be too. Then I would draw back – for, to me, marriage continued to seem like the end of the road.’ And as the trap she most feared seemed to close on her, Phyllis blundered into yet another reckless relationship.

A good-looking redhead, with confidence bordering on arrogance, Stephen was another young man who had paid court to her at the bank, before disappearing – like Don – for overseas RAF training. That autumn he returned and quickly homed in on Phyllis. His glamour, domineering manner and well-travelled sophistication rendered her helpless, and she soon persuaded herself that it would be unkind not to ‘help him enjoy his leave’. This didn’t mean sleeping with him: ‘Stephen was willing to accept that our relationship must for the time being remain platonic … Andrew remained my lover but had to put up with my temporary desertion each time Stephen appeared on leave.’ Then in March 1943 Phyllis was accepted by the WAAF. She put herself down to train as a meteorological observer. Soon after, Stephen proposed to her and, swept off her feet, she accepted. That night she agonised about what she had done. This was a man she barely knew, had hardly kissed, felt no physical attraction for, and yet she could be pregnant by Andrew. Her family reacted with predictable horror, but Phyllis, now wearing a diamond and garnet cluster on her finger, was too deep in to backtrack. Circumstances came to her rescue, but the cost was high. Stephen’s aircraft crashed. He survived, severely burned, after being pulled from the wreckage. When she visited him in hospital, he honourably suggested releasing her from the engagement, which initially she felt unable to agree to. ‘But … whatever had drawn us together was waning.’ They parted, and she returned the pretty ring, feeling she had learned a damaging lesson. Lovers were one thing, a husband was quite another.

*

Times were changing. For women in wartime, the wages of sin were often automatic dismissal, but no longer always automatic disgrace.

Meanwhile, male attitudes

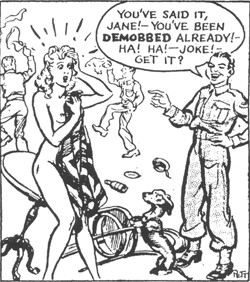

remained predictably primitive. In time-honoured fashion, men continued to achieve a mental disconnect between their sexual and emotional needs. The pin-ups of bosomy Hollywood starlets and scantily clad cutie-pies adorning army accommodation and Spitfire fuselages played into a fantasy driven by lust and loneliness. So did ‘Jane’,

*

the

Daily Mirror

’s famous curvaceous cartoon blonde, credited with boosting troop morale every time her skirt got caught in a door or she lost her towel on the way to the shower. And if centre-fold girls didn’t do enough to quench a man’s libido, there were plenty of real-life vamps out there ready and waiting to do their bit. Servicemen away from home could take a ‘pick’n’mix’ approach to the locals, the amateur fun-lovers and the so-called ‘good-time girls’. If you were in a hurry, or in transit, you consulted the graffiti on the toilet walls at barracks: ‘Try Betty, she’s easy’ and so on.

Ex-WAAF Joan Tagg

remembers that when she was stationed at Oxford ‘there was a girl there called the camp bicycle. I didn’t know who she was, but all the boys there who needed her would have known.’

‘Jane’, with only a union flag to preserve her modesty.

Where there are soldiers there are camp-followers. Wherever it might be, at home or abroad, the army attracted another, shadier army of women cashing in on a captive market and (in Britain) a law which turned a blind eye to the activities of street-walkers. The blackout favoured their dubious trade; in London they were dubbed the ‘Piccadilly Commandos’. The numbers of such women reflected the increase in conscripts and, to the dismay of the health authorities, venereal infections showed a parallel proliferation. In the first two years of the war new cases of syphilis in men were up 113 per cent, in women 63 per cent. With the arrival of the GIs such diseases reached almost epidemic proportions. Outside Rainbow Corner – the American servicemen’s club on the corner of Shaftesbury Avenue – the ‘Commandos’ were like bees round a honeypot;

one US staff sergeant

recalled how they swarmed round the darkened West End:

The girls were there – everywhere. They walked along Shaftesbury Avenue and past Rainbow Corner, pausing only when there was no policeman watching … At the underground entrance they were thickest, and as the evening grew dark, they shone torches on their ankles as they walked and bumped into the soldiers murmuring, ‘Hello Yank’, ‘Hello Soldier’, ‘Hello Dearie!’

Apparently

they often issued a supercharge

of $5 – ‘to pay for blackout curtains’. Sex was on the streets as never before. Less recognised is that some of these prostitutes were themselves servicewomen.

Flo Mahony was a WAAF

who shared her accommodation at her Swanage base with a pretty young woman named Phyllis, who regarded the nearby men’s camp as a business opportunity:

She was a WAAF driver – a great friend of mine, and she had been a prostitute … Well, she would get dressed up and go off out at night. We covered for each other – and obviously we all guessed. She had red cami-knickers, she’d always got perfume and she’d always got talcum powder – things which were quite difficult for us to get. We never talked to her about it, but she went with servicemen I suppose. We all liked her, and she was no trouble to us.

The army was also a two-way traffic for sex workers: the services might offer an escape route to women trapped in a degraded profession – ‘

I’ve been working in London

for years as a prostitute,’ one of

them confided to a fellow recruit, ‘and I joined up to try to leave it all behind me.’

The Wages of Sin

Meanwhile, four years of war had not shifted men’s deeply rooted presumptions as to what they felt owed by women. On the one hand, they wanted to go to bed with them. And men could be selfishly persuasive if they wanted sex with married women: ‘

A slice off a cut loaf

ain’t missed.’ On the other hand, they wanted to be mummied, fed and looked after. They expected fidelity, modesty, domesticity and duty. Scattered over battle fronts from Mandalay to Mersa Matruh, husbands and boyfriends now nurtured the dream of coming home to find their domestic goddess fantasy intact. But things were changing.

Disturbing clashes

often resulted:

‘How can I be sure she will be true?’

‘Every time my husband comes home on leave I am terribly thrilled. But when we meet it is nothing but silly little squabbles.’

‘My wife is working on a farm and I am in the Army … Each time I come home I see her being very friendly with the farm men. I feel angry and suspicious.’

‘He asked me to clean his army boots for him.’

In 1939 there had been just under 10,000 divorce petitions. Now, not surprisingly, divorce rates surged. Women – and men – often embarked hastily and ignorantly on marriages which they then repented. But the millions of wives working in factories and army camps didn’t have time to keep the home fires burning. The domestic goddess had hung up her apron and donned overalls or battle-dress. She was out earning good money and she was placing her duty to her country above her duty to her home. By 1945 that figure had increased to 27,000 petitions, 70 per cent of these on grounds of adultery. Had it not been for the conviction among many respectably brought-up girls that ‘hanky-panky’ was wrong there would surely have been many more.

But if innocence, trust and tradition got misplaced along the way, well, there were compensations. Making love in the crags or amid the bracken, dancing the rumba, spring nights and beautiful young men all helped to banish the miseries of war – and who would blame anyone for trying to do that?

*

Jane Howard’s baby

daughter Nicola had made an inauspicious start to life in 1943. Jane had endured a wearisome pregnancy and gave birth three weeks early after a long and agonising labour. In the following weeks she tried and failed to love the screaming little scrap who had cost her such pain and fatigue. ‘I’d not wanted her enough and was no good as a mother.’ She put her love affairs before her child at this time, and many years were to pass before her maternal feelings eventually matured.

Babies, however, were very much wanted by the powers that be. Before the war, there had been much wringing of hands over the decline of the birth rate in Britain. By 1939 it had dropped to below replacement levels, with 2 million fewer under-fourteens than in 1914, and a worsening situation developing by 1941. With worries about a shrinking and ageing population

the correspondence columns

of the press were deluged with anxious letters, of which the following are typical: