Microbrewed Adventures (17 page)

On one such journey, while touring the countryside along the river Thames west of London, I was absolutely thrilled to encounter the ales of the Brakspear's Brewery at Henley-on-Thames. Brakspear's Bitter was considered one of England's greatest beers. It certainly enlivened my heart as I enjoyed the rich taste of East Kent Goldings hops and the full flavor of countryside English malt, skillfully brewed and fermented at the 200-plus-year-old brew

ery. I found the malt and hop character I seek in English ales both on tap as real ale and in bottles. What was most extraordinary was that I especially enjoyed the Ordinary, likely brewed at 1.038 or thereabouts, low in alcohol (3.4 percent by volume) but bursting with flavor. Keep in mind that this was a full-flavored ale that you won't find in most American brewpubs or in a craft-brewed bottle. How many craft pale ales can you name that start with gravities

below

1.040 (10 B)? They hardly exist. But to tell you the truth, you can get a full-flavored and satisfying ale at these low gravities by infusing extra malt and hop flavor.

British ale enthusiasts mourned the closing and razing of the brewery in 2002, making way for profit-friendly housing developments in the small town of Henley-on-Thames. The beer became contract brewed elsewhere, but it has been a shadow of its former self. The brewers continue to adjust their brewing process, attempting to bring back the original character of a national treasure. They will come close, but I fear that technology and new techniques will interfere with the traditions that once produced one of the finest ales on earth.

The anomalies of Brakspear's will never be studied in today's brewing research laboratories, simply because their methods do not agree with modern brewing and fermentation theories and philosophies. That's too bad. There is much that could have been learned from breweries like the historical Brakspear's Henley-on-Thames brewery and their superb world-class beers. The beer speaks for itself, though the techniques are contentious to many of the learned and the scholarly trained.

Â

I'VE BEGUN

my world beer adventures with recollections of England. These beers and brewers were the beginnings of my own homebrew journey. But I have discovered since, as you will too, that the world is full of great beer endeavors, and one country's border is yet another's frontier. I continue striding out of bounds and normality, into the intimate realm of personal experiences. Each journey provides the foundation of all great beer, great brewers and microbrewed adventures.

Unraveling the Mysteries of Mead

M

EAD IS THE HOLY GRAIL

of brewing. It has a storied history dating back thousands of years. The earliest written records of meadâthe Sanskrit Rig-vedaâdate back to 3000

B.C

. There is no doubt in my mind that the unwritten history reaches back even farther, 10,000 years or more. The Anglo-Saxon epic

Beowulf

from 700

A.D

. describes mead halls and mead benches. The Welsh king Howl the Great introduced royal legislation on making meads in 950

A.D

. In the 14th century, mead reached its greatest popularity in England and was prominently featured in Chaucer's seminal work,

The Canterbury Tales

. In the 1400s, large-scale importation of cheap foreign wines into England brought a rapid decline in mead production, but it continued to be made commercially for another 300 years. The last written reference to the public sale of meads in England is seen in 1712, in Addison's “Coverly Papers.”

1

So what has happened to mead, the original ale, nectar of the gods, an elixir derived from the fermentation of honey, water and yeast? How has it managed to survive the past 300 years? Well, a few great mead makers, microbrewers in their own right, have kept the tradition alive, and I have been lucky enough to meet and linger in the wisdom and company of two of themâ¦.

The Secrets of Buckfast Abbey

Brother Adam

I

ENJOY

tasting all of life's small and big flavors. Some beckon, some flirt, while others attempt to escape. Not all reveal themselves completely, but the ones that do are epic.

In the summer of 1993 I found myself sharing dinner with 40 Benedictine monks in the Devonshire countryside of England. The ceilings arched above while the evening light filtered through the narrow windows to the west, creating a mood of reverence and awe. Prayers had been read, and only the busy clatter of knives and forks broke the silence in this centuries-old dining hall furnished with simple wooden tables and chairs. I tasted, savored and dwelled on the moments. They were everywhere. A background smell of furniture polish and the mustiness of old stones crept into my being. The experience of dining with monks swept my imagination back in time within the walls of this old monastery.

The meal was accompanied by a stoneware jug of amber liquid. I poured myself a glass. It was ale, English ale. Almost flat, served at room temperature, it was a bit ciderlike. Had it been homebrewed at the abbey? Knowing its origins seemed irrelevant. The recipe was nothing I'd ever pursue. Still, its mere presence enhanced its quality. I continued to taste and savor the moments. They were everywhere.

I spent that night in the monastery. Robed, hooded and slippered monks quietly walked the dark halls of the cloister. At the 9:15 curfew, the doors would be bolted shut from the inside. The lure of local ale collided with the fear of being locked out, almost discouraging me from a few evening pints just down the road at one of the quiet town pubs. Temptation won out, and I managed to make the most of the twilight hour, enjoying a few pints and rushing back to the stone abbey, returning in time to hear the bolts slam shut throughout the building five minutes later. The halls were dark. My footsteps echoed on the hard stone floors as I groped my way back to my room. All was still as I retired. The single high, small window in my room promised morning's first light and the sound of bells at 5

A.M

.

I had not come to the monastery for spiritual reasons, or so I thought. Why, then, had I found myself at Buckfast Abbey, asleep inside a small, spartan room? I had traveled all this way from America to the Devon countryside in the southwest of England to see a man whom I had admired from afar for many years. I must admit that the admiration was not one that at first seemed to be a

profound calling. But for a kind of reason that always seems mysterious to me, I had appointed myself seven years earlier to make the pilgrimage to this place, across the Atlantic, to meet and be in the presence of Brother Adam. Why? Because Brother Adam and I shared a rare interest in making and appreciating honey mead, a fermented “wine” of honey and water. Mead enjoys a tradition preceding beer and wine. There are very few people who know its secrets. For years I have been slowly trying to discover and unravel them.

Born in 1898, Brother Adam had retired from a life of devotion at Buckfast Abbey, a life that began upon entering the monastery at the age of 12 after having emigrated from Germany to England. His interests led him to study and breed honeybees for more than 75 years, traveling hundreds of thousands of miles throughout the world to crossbreed his very personal collection of bees. The hybrid Buckfast bee is known throughout the world for its favorable characteristics and resistance to disease and parasites.

In his own small but magnificently significant way, Brother Adam had helped assure fruit, vegetable and nut harvests throughout the world by developing bees that survive to pollinate flowers and assure crops.

Brother Adam's mead-making began as a pleasant byproduct of bee breeding in 1940. When I visited in 1993, it was still a tradition at Buckfast Abbey, reserved for moderate enjoyment by monks at the monastery. For over 50 years he had found the challenge of making traditional mead a side interest, much as I have found brewing and drinking beer and mead a side interest of mine and one of the many intriguing and beguiling aspects of life.

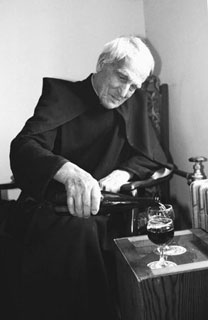

Brother Adam

Far more than a mead

maker, Brother Adam provided me with an insight into devotion. A man of 95 years, his spirited walk and generous hospitality were mere reflections of a long and meaningful life. His memorable voice, though somewhat unclear with age, was a reflection of unfathomable knowledge, patience and sentience only devoted persons possess.

I spent all of my morning pouring through Brother Adam's file on mead makingâshort articles on the subject, references, recipes, experiments and formulations recorded over the past 30 or so years. They all fit into a small hatbox. The formulations were rather simple. Experimentation was indeed part of the progression over the years. Yet there were no copious stacks of recipes or piles of research papers. Brother Adam's procedures were as modest as those of any modern-day homebrewer or mead maker. He “brewed” mead in 60-gallon batches and fermented it in large oak barrels. Wine yeasts were used, but were often difficult to get in England during the early days of mead-making at the abbey. Nutrients were essential, and his experimentation with small amounts of cream of tartar, ammonium phosphate and citric acid provided the vitamins needed for complete and dependable fermentation.

Light clover honey was found best for dry and/or sparkling meads, while darker honeys such as the abundant heather honey found throughout Britain was more suitable for sweeter, sherry-type meads. Brother Adam found soft water to be essential, along with a brief two-or three-minute simmering boil and a skimming off of the coagulated protein rising to the surface.

The fermentations were long and complete. And if the strength or gravity of mead was lacking during the initial stages of fermentation, more honey was judiciously added.

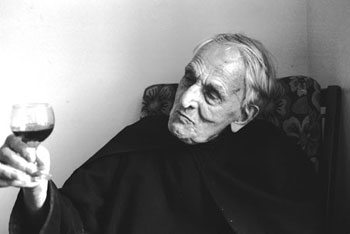

After lunch with the brothers of the abbey, I returned to Brother Adam's office, now brightly lit as the afternoon sun accented the blues and greens of the world outside. Inside, the golden walls were trimmed with natural wood. Not far outside his office door, very large vats of honey provided comfort. But not as much comfort as his storied conversation, accompanied with bottles of his 10-year-old heather honey sherry mead and four-year-old sparkling clover mead.

Brother Adam spoke of his life, about which I had known very little. For two hours we talked. There were frequent pauses of silence as he attempted to recall memories of his past 83 years at the abbey. Brother Adam apologized for his frequent yawning. When one reaches the age of 95, he confided, weariness comes more often.

We spoke of mead, but I soon realized that this was only a very small part

of his story; a morsel, a little flavor, but one that no doubt inspires someone like myself to explore the meanings of the reasons why.

We both often paused to contemplate and savor the ambrosia in our glasses. Saturated with antiquity, the mead refracted sunlight as deep amber. Its aroma was very big, floral and honeylike. Closing my eyes, I perceived an earthy aroma. An infusion of alcohol titillated my nostrils. The flavor began unusually soft and gently sweet, then flirted with fruitlike acidity, finally retreating to a wonderful sherrylike aftertasteânutty, but not overbearing nor overly sweet. The green grass outside in the courtyard sparkled in the sunlight. I began to hear bees buzzing. They were on the other side of the window, seeking our glasses of mead. Smart bees.

Brother Adam recounted the making of his first batch of mead. That was in 1940. There was an abundance of heather honey. What to do with it? Heather honey, having somewhat of a gelatinous nature, was not as suitable for sale as other types of honey. The first batch of mead was made with very little knowledge of the process. I couldn't help but reflect that 53 years later, the mysteries of mead-making remained enveloped in antiquity, awaiting discovery by individual mead makers.

I am not the monastic type. I spent only 24 hours in Buckfast Abbey, but I came away wondering how my small, whimsical notion of seven years back could have led to such an inspiring experience.

Brother Adam, Buckfast Abbey 1993

ST. BARTHOLOMEW'S MEAD

Saint Bartholomew is the patron saint of mead. Considered mystical and held in the highest esteem, mead was originally made from the washings of beeswax. Every church used candles. Honey was washed from the beeswax and fermented into the ambrosia whose sale often provided welcome revenue to the church. St. Bartholomew's Mead is my original and simple recipe. This mead is the pure essence of the art and tradition of mead. It's easy to make, while offering all the complexity and pleasure mead has wrought for thousands of years. The recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

Short glimpses, small tastes and brief digressions. With no real agenda I had wandered onto the grounds of Buckfast Abbey, somewhat purposefully but not expectant. An immersion into the sights, sounds, feelings, aromas and flavors of this place slowly impressed upon me the value of seeing with your eyes closed, tasting with your mouth empty, smelling with only your mind, feeling without touching and hearing through sound barriers.

I bade farewell to Brother Adam late in the morning. I happened to find him walking the halls of the cloister carrying an electronic typewriter. I thanked him for offering me some of his time. He hoped that I found his conversation and information of interest. They were.

Was it a mere whim I had had seven years earlier? Perhaps. Or perhaps it was something else, something that mead makers understand. A yearning for a simple small taste had led me to something much more intriguing. The unexpected always surpasses the expectations of original desire.

Little tastes, little flavors, notions, whims, fancies and small gestures. This time they've complemented a journey I will never forget. This seems always to be the story of mead and its mysteries. A friend of mead is a friend indeed.

One year after my visit, Brother Adam died. His passion surely has left an indelible mark on these lives we still live.

Minard Castle,

Argyll, Scotland

F

ROM THE DEVON COUNTRYSIDE

I journeyed north to the brisk and rustic landscape west of Glasgow, Scotland. Mead had been foremost in my mind for a week, and now I had arrived at the beginning of another adventure back in time. I found myself sipping 45-year-old mead in the wine cellar of a centuries-old Victorian castle. In my hands I held experimental meads brewed both before and during World War II. The walls of the castle were several feet thick. The silence of the room was total, though the rain and gales blew outside, scouring the Scottish countryside.