Metallica: This Monster Lives (7 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

Bruce and I spent much of that time getting acquainted with the special needs and excesses of rock stars. Jann Wenner, editor and publisher of

Rolling Stone,

hired us to do a television special for ABC commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of the magazine. We pitched him on the idea of doing interviews with real people from a cross section of American subcultures, intercut with interviews and performances from rock-and-roll icons. The show was excruciatingly difficult to make. Wenner hired us late in the game, so we had very little lead time. The show was also a real eye-opening experience. I learned a lot about how wildly extravagant and difficult some rock stars could be and how cool and normal others were. Bruce Springsteen, for example, could not have been warmer or more down-to-earth. He pulled up to Sony Studios in New York City, driving his own vehicle, a modest Jeep Cherokee, without an entourage, and played his heart out for us. After giving us an extra song, he asked if we got everything we needed, and said he’d be happy to play some more. Marilyn Manson was also great to deal with. He invited us up to his bedroom and gave us a sneak preview of his new album,

Mechanical Animals,

while he sat on his knees like a little boy. Fiona Apple, on the other hand, was late, surrounded by handlers and sycophants, and generally difficult to work with. At her insistence, we flew in her own personal and ridiculously expensive hair and makeup person, whose work on Fiona, as far as I was concerned, did not justify the outrageous expense.

The hassle of putting together the

Rolling Stone

show cooled some of my ardor for making a movie about rock stars. But by 1999, we were once again thinking about Metallica. We found ourselves back in Arkansas to make

Revelations,

the sequel to

Paradise Lost.

The West Memphis 3 were still rotting in prison for a crime they didn’t commit. An international West Memphis 3 support network had arisen as a result of

Paradise Lost.

Bruce and I were very proud that our film had finally gotten off the entertainment pages and was actually affecting some social change. We thought the activities of the WM3 activists, which included the hiring of a new forensic expert to re-examine the crime, would make an interesting sequel. Creatively, we were a little weary of treading the same ground, but we felt that Damien, who was on death row, needed our help. In the editing room, we realized the film, like its predecessor, cried out for Metallica music. We weren’t shy this time: we asked for thirteen songs and got all of them. It’s standard for musicians considering film requests to ask to see the footage that will include their music, but Metallica said they trusted us completely Once again, we were impressed with how easy it was to deal with Metallica.

We seemed to be establishing an actual productive relationship with the

Metallica organization. Cliff Burnstein even brought up the film idea with us that summer. Of course, it wasn’t really the type of film we had in mind, but surely we could work something out. It was with high hopes that we made our way to the Four Seasons.

“This ain’t gonna happen.”

“No shit.”

This was the sort of terse exchange that was becoming increasingly common for Bruce and me. We always seemed to be getting on each other’s nerves. We didn’t speak as much these days, and the less we spoke, the more we needed to. Long-standing problems with our working relationship were reaching a crisis point. Our renewed eagerness to make a movie about Metallica was one of the few things holding us together. After having our idea shot down for what looked like the last time, our relationship got progressively worse over the next several months.

My problem was that I was tired of feeling like we were joined at the hip as filmmakers. We did such a good job of marketing ourselves as a filmmaking team that it was increasingly hard for one of us to get hired for a job without the other. Clients would be afraid that if they didn’t get both of us, the project wouldn’t have that Berlinger-Sinofsky “magic.” The more we stayed together and sold ourselves as a team, the more individual careers seemed unobtainable. I thought it was bad for business to be in this situation; I didn’t want to have to rely on someone else to be able to get gigs.

There were also deeper emotional reasons for my unrest. First of all, although we billed ourselves as a team and shared all the profits, I was the one who really ran our business. I put in a lot of extra hours and was starting to resent it. Because Bruce and I weren’t able to grow our business beyond a handful of underpaid junior staffers (documentaries aren’t exactly a gold mine), I was stuck with a lot of extra duties—some I loved, others I resented. I was largely responsible for developing and pitching ideas in the concept stage. Once we got the work, I dealt with all of the legal, marketing, and financial work that comes with running any company. At the end of the creative day Bruce would go home and have dinner with his family, while I was stuck in the office. To be fair to Bruce, he always said that he wanted to do more but felt like I was too much of a control freak to let him take on more responsibility. The truth is

somewhere in the middle. I am a control freak, but Bruce lacked the business and marketing skills that I had absorbed during my years in advertising. Truth be told, I also enjoyed running the show. Looking back on that period, I think I even got off a little on being a martyr.

I also became obsessed with trying to put a value on the creative input each of us brought to our work. Years later, eavesdropping on Metallica’s therapy sessions, I realized that when a group comes together to create something, there’s a collective alchemy that can’t be reduced to a straightforward accounting of who does what. But in 1999, I was still a long way from that epiphany. Bruce and I found ways of quantifying our respective contributions. We agreed that the intellectual depth and complex structuring of our films generally came from me, while his contributions tended to give the films then emotional resonance and humor. Bruce likes to say that I’m a “type-A-plus” personality and he’s a “type-B-minus.” I’m high-strung and obsessive, he’s relaxed and “big picture.” This is true, as far as it goes. My temperament is such that I agonized over every detail, closely examining every cut we made. If I complained that he wasn’t as engaged, Bruce would tell me that my attention to detail had a downside—that I’d get lost in minutiae, and that it was he, with his knack for seeing the forest for the trees, who often brought me back to the middle. These sorts of explanations just weren’t working for me anymore. I became obsessed with trying to determine a way to credit both Bruce and me for our respective contributions to our work. The fact that I sweated the creative details

and

got stuck running the business made me feel like my contributions were greater—a dangerously egotistical assumption. Bruce started to resent my control-freak personality and my whining about all of the extra time I was putting into the company, since it implied that his contributions were not as significant as mine. In short, we were headed for a breakup, but we didn’t know how to face it.

Part of the problem was my reluctance to deal with confrontation. Having spent my childhood trying to make volatile situations within my home go away, I have always tried to avoid disputes. Further complicating the situation was that Bruce and I were the best of friends; we cared deeply for each other and our respective families. We had had some of the most incredible experiences on the road that any two friends could have. My reluctance to break away stemmed in part from a guilt complex; I didn’t want to abandon my friend and cause him financial problems. Since I was the guy who was the primary rainmaker, the one who squeezed every drop of profit out of our jobs, I feared that

I would be inflicting financial and emotional damage on my friend if I dissolved our business.

My concerns weren’t limited to issues of ego and credit. I also became convinced that each of us should make films that expressed our singular voices. The vague solution I came up with was that we should just start looking harder for projects we could do independently of each other. My thinking was that this would be an organic solution to the problem, one that didn’t require us to actually talk to each other about it. I was ostensibly exploring ways for our production company to work at full capacity, using the logic that two directors working on two projects was a more efficient allocation of resources than two directors working on the same project. I also figured that if we each looked for our own gigs, we might grow apart naturally and with no resentment. In my heart, I knew I was laying the eventual groundwork for dissolving our business partnership, one way or another. I told myself that I wanted to give Bruce plenty of time to start developing his own individual career. That way, when and if we parted ways (and I knew that really meant “when”), it wouldn’t be a sudden shift. The only problem was that I didn’t bother to tell Bruce the real underlying reasons why I thought we should both look for separate work.

I quietly went about establishing my own career, and it looked to me like he was doing the same. I landed a few TV gigs, including directing an episode of

Homicide

and a short-lived drama called

D.C.

Bruce was also gaining traction on some projects, including

Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy of Sun Records,

which he made for the PBS series

American Masters.

(It was hard to turn down Bruce’s offer to work on the film with him, because it promised to be a lot of fun.) So, as the elevator doors opened on to the Four Seasons lobby, and we walked through the lobby where we’d just recently wasted four hours waiting to talk to Metallica, it felt like one of the last strands holding us together was being severed.

For me, Metallica would not go away In the fall of ’99, a few months after the Four Seasons meeting, I pitched an idea for a TV show to Lauren Zalaznick, then head of programming at VH1, a really bright executive who had coproduced the movie

Kids

and then gone on to revitalize the moribund VH1 with some very original shows. My idea was for a show called

FanClub,

which I envisioned as the flipside of

Behind the Music.

Rather than focus on the history of rock groups, my show would tell the story of their fans. Each week, we’d profile a few of the most hard-core fans of a particular group, then intercut those profiles with performances and interviews with that band. A pilot was green-lit.

Since I already had a relationship with Metallica, I turned to them. I told Q Prime that this would be a good way for all of us to work together. Since the archival documentary wasn’t happening, the VH1 show would also help keep Metallica in the public eye during the following year’s planned hiatus. They went for it. I caught up with them on tour and filmed some hotel interviews and live performances. For the latter, I had to deal with the Metallica road crew. Their attitude made me realize that Metallica were no strangers to being in front of the camera; if I ever really wanted to make a personal film about the band, I’d have to really make clear how ours would be unique. The vibe I got from the road crew was basically: “You’re no different than the thousands of other video guys, reporters, photographers, and assorted hanger-ons who get in our way on a daily basis. Here are the rules. Don’t break them and don’t fuck with our jobs.” (Winning over the road crew was one of the major challenges we faced while making

Monster.

)

The making of the

FanClub

pilot went well. Bruce and I continued to drift apart. I sensed my big break was right around the corner. I had no idea it would break me.

CHAPTER 4

THE WITCH’S SPELL

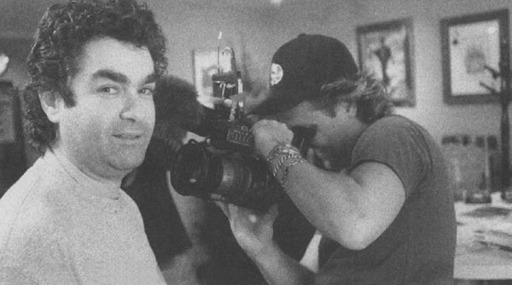

For a brief moment, the cameras are turned. Lars and I really bonded over the making of this film. (Courtesy of Bob Richman)

04/21/01

INT. ROOM 627, RITZ-CARLTON HOTEL, SAN FRANCISCO - DAY

LARS (to Phil):

Do you feel that me, Kirk, and James are in any way different right now than we have been in the last couple of months, because of either Bob being in here or the cameras being in here?

PHIL:

There’s been a transformation. I’m anxious to see how you guys take what you’ve been working on in here, and take it into the studio and into your performances and your personal lives. I think you guys now seem very natural.

LARS:

It feels better. It doesn’t feel forced.

PHIL:

What’s cool is that I don’t feel like there’s been any concern about the cameras. I wasn’t thinking people would be shy, but I did think there might be a little showboating. But I think this has been a real natural expression up to now. I really like it.

LARS:

Yeah, I agree. (to

James

) Do you feel the same way?

JAMES:

Yeah, cameras, fine. But microphones, though, I’m, uh …

BOB:

Well, what we’ll try and do is, we’ll try and get rid of all the microphones at the studio.