Metallica: This Monster Lives (41 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

CHAPTER 20

FRANTIC-TIC-TOCK

Technical difficulties with mastering

St. Anger

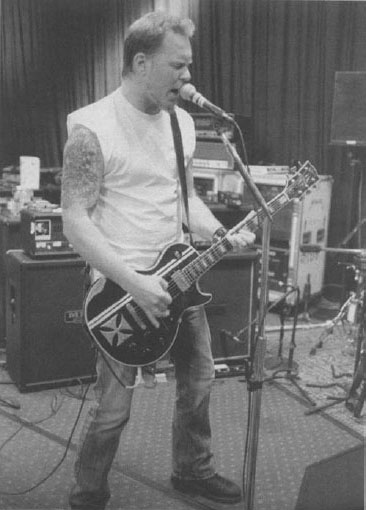

gave us a much-needed opportunity to show the band some footage from the film on a special chartered flight back to San Francisco. (Courtesy of Bob Richman)

The first few months of 2003 were a blur of activity.

After two long years, much of it spent in a state of lethargic disintegration, the new Metallica album was actually starting to come together. A June release date was set, and tentative talks about summer touring began. This was a delicate subject, given James’s rehab travails. Life on the road would present some serious challenges to James’s new lifestyle. And his lifestyle, as James sang (but Kirk wrote) on the rapidly coalescing “Frantic,” could very well determine his “deathstyle.”

There was a light at the end of the tunnel for us as well. If the album was nearing completion, that meant principal photography on

Monster

would reach a natural termination point, allowing us to return from the front and actually get to know our families again. The questions that had dogged everyone from the beginning suddenly became more urgent: What exactly were we making? And for whom were we making it?

Back in the spring of 2002, when Elektra created the therapy-less trailer, there had been talk of us creating an

Osbournes

-like reality show. Most of the series would precede the album’s early-June 2003 release date. The penultimate show would air the day the album came out, and the last episode would lead up to an exclusive live concert. I was dubious that any network would be interested in such a show without the therapy scenes, but my first advice to

Elektra execs had been that if they really wanted to do this, they’d better hurry up, since the pitching season is normally June and July—

maybe

August, if you’re lucky. I had on several occasions set aside time to go pitch the show in L.A., but the meetings never materialized. (Or if they did, I wasn’t a part of them.) Since we had a special relationship with Sheila Nevins at HBO (our patron on the two

Paradise Lost

films), we had pitched her directly, without Elektra. By October, she had passed, feeling that this material was not right for her

America Undercover

audience.

The summer buying season came and went. By Thanksgiving, Bruce and I assumed Elektra had abandoned the idea, since it would be nearly impossible to meet the necessary deadline. That was fine with us, since by now we were absolutely convinced that we had an incredible feature film on our hands. We’d known for a while that we had great footage, but in the last six months, as Metallica found its strength again, we now had an actual dramatic arc. We assumed that some of our footage would be used for its original promotional intent—electronic press kits, TV clips, maybe a bonus DVD packaged with the album—but we also figured that since nobody had really pitched the series, our material would become a feature film by default. On December 19, we were jolted back to reality.

I was in the editing room when I got “the call.” It was from the Elektra executive who had day-to-day responsibility for Metallica and therefore this film. Marc Reiter of Q Prime was also on the line. “We need to start thinking about turning your footage into the series we talked about so it coincides with the album release date,” the exec said.

I didn’t say anything for a second, wondering if I’d heard wrong. If the album was coming out the first week in June, our series would have to be delivered by the beginning of March. My vision got blurry. “To be honest,” I said, “I thought that idea had gone away—at least the idea of timing it to coincide with the album’s release. The pitching season has come and gone, and HBO passed. We haven’t been cutting a series, just gradually whittling our material down. Isn’t it too late to sell this thing for a March delivery?”

“We have some interest from Showtime.”

I began to break a sweat. What I was feeling wasn’t disappointment—it

was panic. A high-profile cable series could be interesting, but this deadline was insane.

“Okay Is it a done deal? Do we know how many episodes?”

“We need to go in after the holidays, show them some material, and talk about all of this.”

I tried to maintain composure, wondering if my voice was shaking. “Guys, it’s almost January I am very concerned about the timing of this. We haven’t been cutting TV episodes. I’m not sure we can deliver a series by March. We are

swimming

in footage. Besides, if this is going to happen, we need to immediately know how many episodes and the length of each episode. We need to hear some thoughts from the programming execs about their take on what kind of show they want. We need to know that we are not going to be inundated with editing notes.”

I paused and willed myself to take a deep breath. Reiter must have sensed the panic in my voice. “Joe,” he said, in a tone that said, “Get a grip.” “This is Metallica. I hate to play this card, but Metallica gets things done against all odds. We always have. Make this happen—that’s why we’re paying you guys. It won’t be easy, but we know you can do this.”

The anxiety made my armpits ache. I called Bruce to fill him in. He agreed that what Elektra and Q Prime wanted was highly unusual, almost unheard of. What network still has a six-hour hole in its spring schedule in the winter? The only possible explanation for Showtime’s supposed interest was that some other programming had been canceled at the last minute. Or maybe we had underestimated this band. Marc Reiter’s words rang in my ears: “This is Metallica.” Was Metallica some sort of illuminati, a secret society with enough influence to get what it wants, even if that meant rewriting the rules of an entire industry? As for us, we had been treated so well by Metallica and Q Prime that we felt obligated to do whatever it took to make this happen, since it was apparently what the band members wanted. I just wasn’t sure how we were going to do it.

The next day, I called an emergency meeting of the entire production staff. Bruce and I dropped the bomb that we needed to morph this production into a television series on a “crash” schedule, just as everyone was looking forward to a much-needed Christmas break. To create six hour-long episodes, we decided that we needed to hire three additional editors to work with David Zieff. The four editors would be connected by an Avid Unity system, which would allow them to share the same digitized media. Each editor would begin by tackling one episode. But before they could do anything, we’d have to redigitize

our footage—by now, it had ballooned to nine hundred hours—for the new editing system. The process of redigitizing and logging just one hour of footage would take about 120 minutes, which meant we’d have to hire an army of digitizers to work around the clock through the Christmas and New Year’s holidays, so that we could begin editing in January. The editors would then have to work six- and even seven-day weeks, racking up serious overtime.

We put together a budget and realized this was all going to cost close to an additional million dollars. All because Showtime had expressed an amorphous “interest.” We couldn’t afford to wait for the network to give the green light before starting the emergency editing process. What if Showtime passed? January is the worst month to pitch new programming to the networks. For that matter, even if Showtime bought the show, who was to say that they would want the show in the form we’d rather arbitrarily chosen, six one-hour blocks? Maybe they’d want four one-hours or eight half-hours. When you’re editing at this pace, those kinds of changes make a huge difference.

Meanwhile—and this was the killer—Bruce and I would have to continue shooting. All of this furious editing would be in the service of a story that was still very much in play. When working on this scale, it’s difficult to put together something coherent without knowing how it ends. There are themes that you want to introduce early in a series that pay off at the conclusion, but we didn’t have the luxury to pursue that kind of nuance. The TV series also complicated our narrative arc, because we’d have to quit filming entirely in March. Many of the artistic considerations we had for the project were now completely unworkable. We had been toying with the idea of making the film nonlinear, beginning in the present, flashing back to the events of 2001 through 2003, and building to the “triumphant return” of the summer tour. But now we’d have to edit and complete each episode before finishing the next, so we’d be shackled to a rigidly chronological unfolding of the story—far less interesting, we thought. Elektra thought we could achieve the same emotional impact by building to a special live concert in front of a television audience, but we didn’t think their ending would be nearly as powerful as the more organic one that we envisioned: Metallica taking the stage on its summer stadium tour, after being out of the spotlight for so long.

As independent filmmakers, Bruce and I were disappointed in this turn of events. Even if we pulled off a successful reality series, the fact is that even the most revered TV shows don’t have the cultural cachet of great movies. But we weren’t indie filmmakers on this project. This wasn’t really our film. We were

hired guns, and this is what our client wanted. They had been good to us over the last two years, and we knew we had a responsibility to create what they wanted us to create. If

Some Kind of Osbournes

was what they wanted, that’s what we’d give them. The businessman in me could appreciate where Elektra was coming from. If I were in the business of selling records, I would probably be dead set on making this a TV show, too. I knew firsthand how perilous a feature film can be, in terms of financing and distribution. Meanwhile, the music business was mired in a slump. The last time Metallica released an album of original studio material had been in 1997, which just happened to be the last year the industry experienced any kind of expansion. There were no sure things anymore; even an act as big as Metallica wasn’t guaranteed a huge album. I knew this project could help boost Metallica’s sales, so the film producer in me vowed to get the job done. But I was also one of the project’s executive producers, and

that

guy wasn’t convinced this was physically possible.

Two days before Christmas, Q Prime approved the new budget. We canceled our holiday plans and worked nonstop. We were anxious to have our

Showtime meeting to nail down the creative approach and confirm the number of episodes. January and February passed with no meeting with the network. We kept telling Elektra that it would be highly unusual, if not outright unthinkable, for Showtime to air this in two months, especially since there had been no talk whatsoever about how to promote the thing, nor had the format of the show been decided. How could a network

still

have that kind of hole in its spring schedule?

Courtesy of Bob Richman

Finally, in early March, we met with people from Showtime’s New York office. It wasn’t a good sign that we were meeting in New York, since I knew the people with buying authority were in Los Angeles. We were meeting with mid-level executives in charge of corporate strategic planning and sports/events programming; in my mind, these weren’t people who could green-light a reality series. But at least we were meeting. And even though we felt there was a better feature film, Bruce and I were going to go in there and pitch our hearts out—if for no other reason than that we really needed our marching orders.

When I arrived at the lobby’s security desk on the day of the meeting, I ran into the Elektra exec who had instructed me to start turning our footage into a TV series. I seized the moment to tell him that, should the Showtime thing not work out, we had the makings of a great feature film.

He wasn’t impressed. “Over my dead body will this be a theatrical film,” he said. “We need to set up the album. That’s why we hired you. Documentaries just don’t do business at the box office.”

“Look, I don’t think you realize how great this material is—”

He shook his head and cut me off. “We want this to be a reality TV series.”