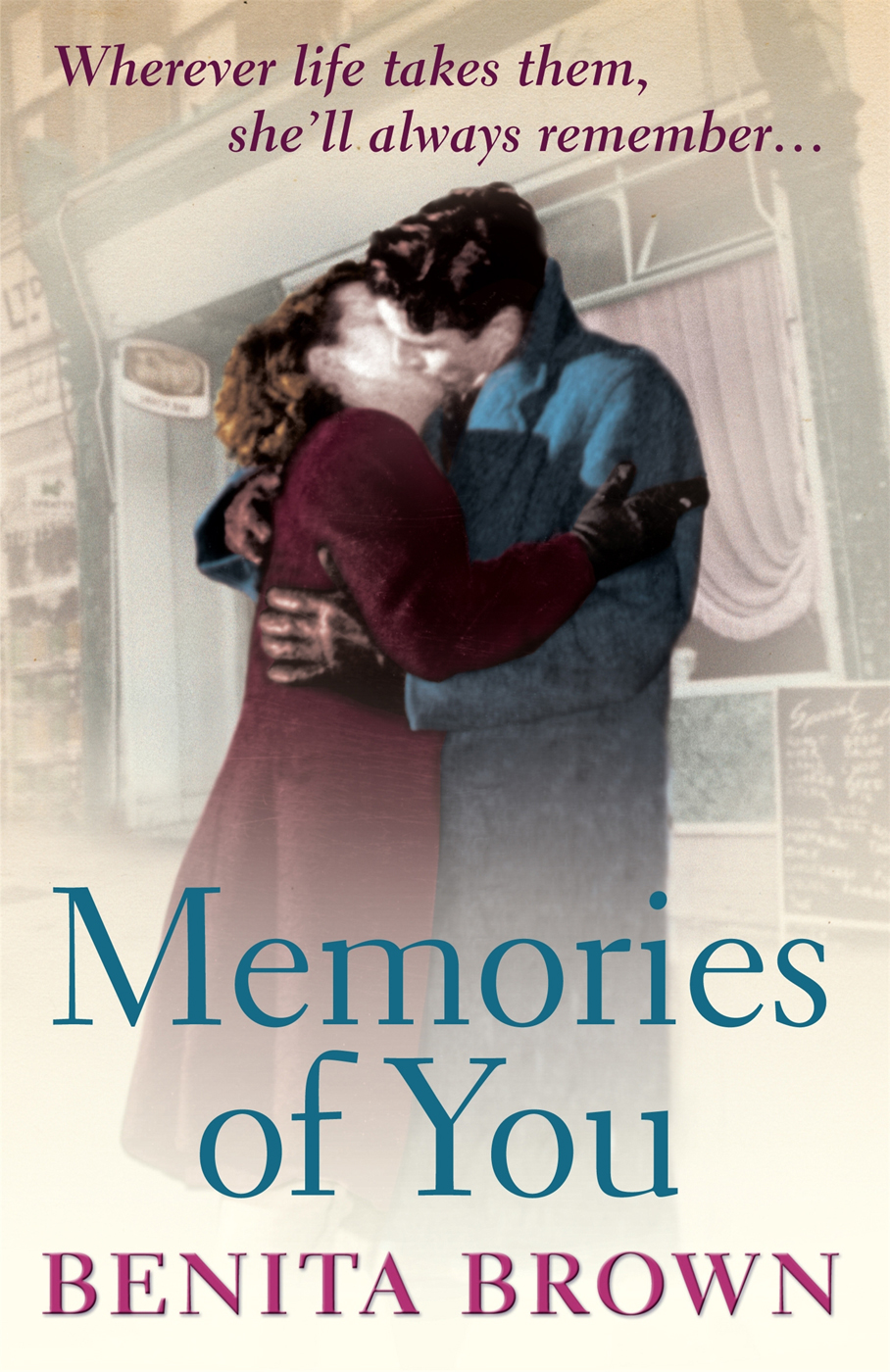

Memories of You

Authors: Benita Brown

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Memories of You

Memories of You

Â

Â

BENITA BROWN

BENITA BROWN

Â

Â

headline

Â

headline

Â

Copyright © 2011 Benita Brown

Copyright © 2011 Benita Brown

Â

Â

The right of Benita Brown to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The right of Benita Brown to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Â

Â

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

Â

Â

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2011.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2011.

Â

Â

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Â

Â

Every effort has been made to fulfil requirements with regard to reproducing copyright material. The author and publisher will be glad to rectify any omissions at the earliest opportunity.

Every effort has been made to fulfil requirements with regard to reproducing copyright material. The author and publisher will be glad to rectify any omissions at the earliest opportunity.

Â

Â

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

Â

eISBN : 978 0 7553 5351 4

Â

Â

This Ebook produced by Jouve Digitalisation des Informations.

This Ebook produced by Jouve Digitalisation des Informations.

Â

Â

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Â

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

In memory of my mother who because of family circumstances had to leave grammar school at the age of fourteen. Like Helen, she left Newcastle to work in London.

I know she would have enjoyed this story.

Part One

The Beginning

Newcastle, November 1929

Selma stared out at the darkening sky. Wind hurled rain and withered leaves against the window panes. Dr Charles Harris was checking through the papers on the desk in front of him. She heard him clear his throat and she turned to face him.

âAs far as I can see from the results of these tests there is no reason why you and Hugh cannot have a baby,' he said. âYou will just have to be patient.'

âPatient! My life is slipping away. I'll soon be middle aged!'

The consultant smiled. âYou married very young, Selma. At twenty-six you are nowhere near middle aged.'

She shrugged impatiently. âI know. I exaggerate. It's my nature. But Hugh is much older than I am.'

âHugh is the same age as me. Thirty-seven. Perhaps if you learned to relax you would conceive. Maybe a holiday? Some winter sun? Would you like that?'

Selma sighed and stared down at the gloves she had been twisting round with nervous fingers. âPerhaps.'

She rose abruptly and her gloves and handbag fell to the floor. Charles hurried round the desk to pick them up, saying, âI'll have a word with Hugh.'

Selma got the impression that he was glad to be rid of her. Inside the car she stared ahead despondently. âTake me home, John,' she said.

The chauffeur turned his head towards her. âWe have to collect Mr Partington from Dean Street, madam.'

âOf course. I forgot.'

Soon they had left the leafy avenues behind them and were driving through the town. Selma gazed at lighted shop windows and blurred forms of people hurrying with heads down through the slanting rain. Near Grey's Monument a policeman raised his arms to direct the traffic, his white gloves standing out against the gloom.

The car slowed down as they passed a stationary tramcar. Selma glanced up at the people inside. Those who hadn't found seats were hanging on to the overhead straps, huddled closely together. A boy, his nose pushed sideways as he pressed against the window, stared rudely into the interior of the luxurious car. When he saw that she had noticed him, he stuck out his tongue. Selma turned her head to look back at him. She grinned, stuck out her own tongue and crossed her eyes. She just had time to register his startled expression when there was an almighty thump and the car came to a screeching halt.

Selma was thrown forwards and she banged her head on the seat in front of her. When her head cleared she became aware of John saying over and over again. âOh God no . . . Oh God no . . .'

âWhat happened?'

âShe ran straight out between the tram and that car,' the chauffeur said without turning to look at her. His hands gripped the steering wheel. âI didn't stand a chance. As God is my witness, I didn't stand a chance.'

The traffic had come to a halt and, as a curious crowd gathered, Selma got out of the car.

âDon't, Mrs Partington! Don't look!'

John opened his door and almost fell out on to the road. But Selma was already kneeling to look down at the woman who lay there. There was no obvious injury and Selma reached for her hand. âDon't worry,' she said. âWe'll send for help. I'll stay with you. I won't leave you here alone.'

âPlease get back in the car, Mrs Partington,' John said. And then, as if talking to a child, he added, âYou'll spoil your lovely coat kneeling there on the greasy cobbles.'

âThat's right, madam.' A policeman had appeared and was standing next to John. âIt's best if you go and sit down.'

John turned to the policeman. âI didn't stand a chance,' he said again. âShe just ran out straight in front of me.'

âI know, lad. I saw it all and so did many of these folk gathered here.' He turned to the crowd. âIf you've got anything to tell me would you return to the pavement and wait. Otherwise, you've stared your fill and it's time you moved on.' He turned to John. âWill you help your mistress? This isn't seemly.'

âNo,' Selma said. âI promised her I'd stay with her until help comes.'

The policeman knelt down and, taking off his white gloves, he gently took the woman's hand from Selma. Taking her wrist between finger and thumb he felt for a pulse. The seconds ticked away until eventually he looked up and shook his head.

âNo!' Selma cried. âShe can't be!'

âI'm sorry, madam. She's past help.'

Selma got to her feet and stared down at the woman. One shoe had come off and there was a darn in her stocking just above one knee. She stooped swiftly and pulled the woman's coat down

.

At least I can protect her dignity, she thought.

.

At least I can protect her dignity, she thought.

As she turned to go her foot caught on something and she stumbled. She looked down and to her surprise she saw an orange, a splash of colour on the rain-dark road. A shopping bag lay nearby, the contents spilled and scattered. More oranges, apples, a loaf of bread, a jar of jam, the glass smashed and the red contents oozing out. Selma stared at the jam in horror

.

She was hurrying home to give her family their tea, she thought

.

They'll be waiting for her. Wondering what treats she's bringing.

.

She was hurrying home to give her family their tea, she thought

.

They'll be waiting for her. Wondering what treats she's bringing.

She climbed into the car and sat there hunched and miserable, her own wretchedness momentarily forgotten. She closed her eyes but she was unable to rid herself of the image of the woman with the slightly surprised expression on her pleasant face. A woman whose homely life had been suddenly and wantonly interrupted.

Chapter One

The last few lumps of coal smouldered in the grate and the room was chilly. Helen sat on the sofa with her younger sister Elsie. She put an arm round her and drew her close. The twins Joe and Danny, in their coats and ready to go, stood near the window, brown paper parcels tied with string at their feet. Every now and then Joe pushed the net curtain aside, and looked out at the drenched cobbles and the rain overflowing from the gutters of the houses opposite. Danny kept his head turned away from the window and stared at nothing in particular. Usually so easy-going and happy, the younger boy was now rigid with misery, his face pinched and drawn. Joe, the elder by ten minutes, simply looked angry.

It had been a week since their mother's funeral but Aunt Jane had left it to the evening before to tell them that they were not going to be staying together.

âI haven't got room for all of them,' she'd told their neighbour, Mrs Andrews. âAnd I can't afford to take two growing boys. They'd eat me out of house and home. It might have been different if Grace had thought to take out a proper insurance policy. As it is, once the funeral's paid for, that's that.'

Jane Roberts, the widow of a bank manager, had shed no tears for her dead sister; nor had she offered any comfort to her nephews and nieces. She had come when Mrs Andrews had sent for her, and she had done her duty. If she had shown any sign of humanity it had been towards the youngest child. But not many people could resist Elsie. Simply to look at her was to make you draw your breath and wonder at her beauty. Her long hair was angel fair, her blue eyes fringed with dark lashes. Small and fragile, she looked and behaved younger than her nine years.

Aunt Jane had been noticeably gentle with her and had encouraged her to eat the plain food she had provided. But Elsie had only nibbled at her bread and margarine and had pushed aside the plates of gristly stew. Eventually Aunt Jane lost patience with her and ignored her.

Today there was a clean cloth on the table in the front parlour and it was set with a generous plate of ham sandwiches and a sliced fruit cake. Aunt Jane had not come to sit with them as they waited. She had remained in the kitchen with Mrs Andrews. She had explained that she had things to talk about, arrangements to make about handing the keys back to the landlord and the like. Helen wondered if the truth was that their aunt could not face them. Maybe she felt guilty. But if she did, there was no sign of her having changed her mind.

Other books

Transcontinental by Brad Cook

The Third Rule Of Ten: A Tenzing Norbu Mystery by Hendricks, Gay, Lindsay, Tinker

Morlock Night by Kw Jeter

Strife: Part Two (The Strife Series Book 2) by Corgan, Sky

Falling for the Marine (A McCade Brothers Novel) (Entangled Brazen) by Beck, Samanthe

Her Heart's Divide by Kathleen Dienne

Perigee by Patrick Chiles

The Nurse's Secret Love (BWWM Romance) by Violet Jackson