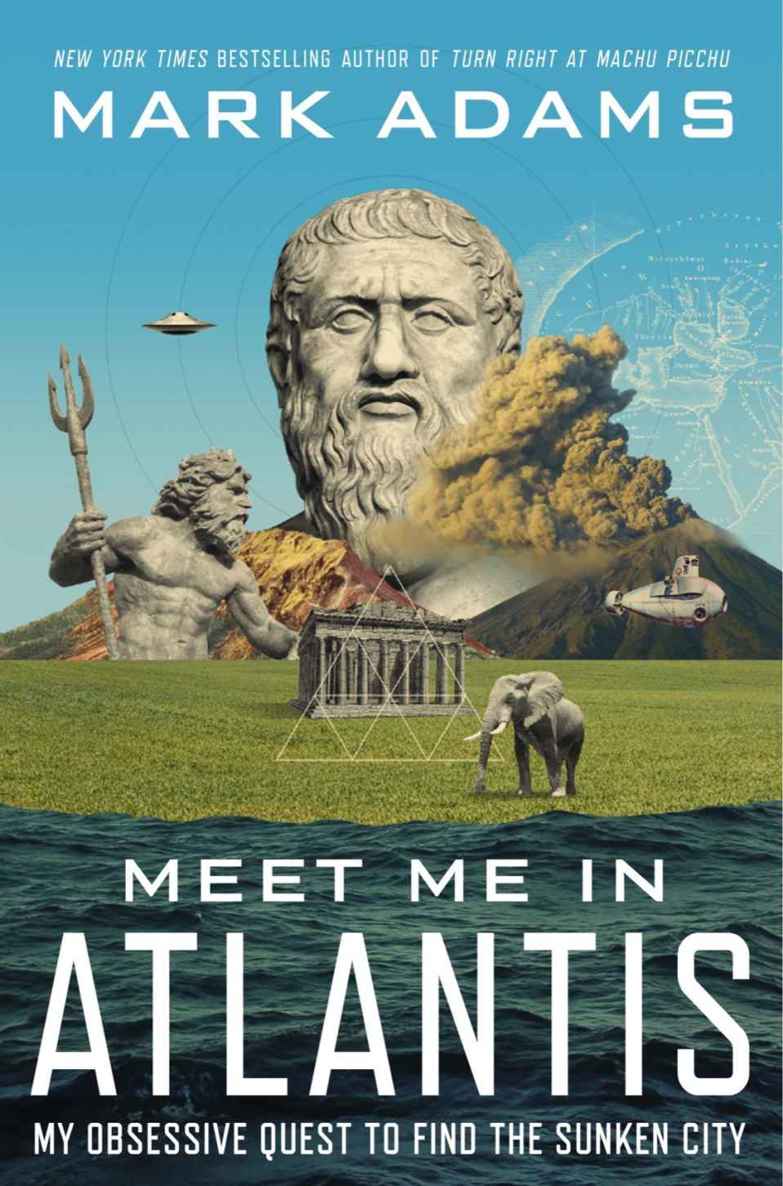

Meet Me in Atlantis: My Obsessive Quest to Find the Sunken City

Read Meet Me in Atlantis: My Obsessive Quest to Find the Sunken City Online

Authors: Mark Adams

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2015 by Mark Adams

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

has been applied for.

ISBN 978-0-698-18621-7

Illustrations copyright © 2015 by Julie Munn

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

CHAPTER ONE | That Sinking Feeling

CHAPTER TWO | Philosophy 101: Intro to Plato

CHAPTER THREE | “Disappeared in the Depths of the Sea”

CHAPTER FOUR | Mr. O’Connell’s Atlantipedia

CHAPTER SIX | Lost City Meets Twin Cities

CHAPTER SEVEN | Secrets of the Wine-Dark Sea

CHAPTER NINE | A Second Opinion

CHAPTER ELEVEN | The Truth Is out There

CHAPTER TWELVE | Dr. Kühne, I Presume

CHAPTER THIRTEEN | The Fundamentalist

CHAPTER FOURTEEN | The Pillars of Heracles

CHAPTER FIFTEEN | The Mysterious Island

CHAPTER SIXTEEN | The Minoans Return

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN | The Front-runner

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN | Scientific Americans

CHAPTER TWENTY | Triangulating Pythagoras

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE | The Cradle of Atlantology

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO | Well, That Explains Everything

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE | “You Don’t Buy It”

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR | The Power of Myth

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE | Maps and Legends

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX | Statistically Speaking

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN | The Sky Is Falling

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT | The Plato Code

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE | True or False

In memory of Kathleen McMahon

Adams

Many cities of men he saw and learned their minds.

—Homer,

The

Odyssey

Lost and Found?

Near Agadir, Morocco

W

e had just met the previous week in Bonn, my new German acquaintance and I, and here we were on the west coast of Africa on a hot Thursday morning, looking for an underwater city in the middle of the desert. Our destination was an unremarkable set of prehistoric ruins. The shared interest—about the only thing we had in common—that had brought Michael Hübner and me together in Morocco for what felt like a very awkward second date was Atlantis. Hübner was certain he had found it.

Hübner was far from alone in this belief. I’d already met plenty of other enthusiastic Atlantis seekers who’d used clues gleaned from Renaissance maps or obscure Babylonian myths or unpublished documents from the Vatican Secret Archives to pinpoint its supposed location. There did not seem to be a lot of consensus. Morocco was the eighth country on three continents that I’d visited as I pursued those who pursued Atlantis, the legendary lost city. I’d become as fascinated by them as they were by their quest. I hadn’t seen my wife and children for a month.

Hübner’s unique search strategy was data analysis. He had scoured

ancient literature for every mention of Atlantis that he could find and then plugged that data into an algorithm far too complicated for a math novice like me to understand. His results were clear, though. According to his calculations and the laws of probability, the capital city of Atlantis had absolutely, positively existed just a few hundred feet ahead at the nexus of GPS coordinates we were tracking. “It is very, very improbable that all these criteria are combined by chance in one area,” he had already told me several times, his monotone voice betraying not the slightest doubt.

I wasn’t so sure. Perhaps the defining characteristic of the landscape around us, the foothills of the Atlas Mountains, was its complete lack of water. Twice on the way here my driver had slammed on the brakes to avoid crashing into herds of camels crossing the road. The one thing that everyone knows about the legend of Atlantis is that it sank beneath the seas.

Hübner had a ready explanation for this aquatic discrepancy. An earthquake in the Atlantic Ocean, a few miles west of where we were hiking, had caused a tsunami that had flooded the Moroccan coast and then receded. The ancient story of this deluge had simply gotten garbled over generations of retelling.

A few months earlier, I would have said Hübner’s explanation sounded crazy. Now it had a very familiar ring to it. I had heard a lot of location hypotheses that hinged on tsunamis and other improbable agents: volcanic explosions, mistranslated hieroglyphics, the ten biblical plagues, asteroid impacts, Bronze Age transatlantic cocaine trafficking, and the Pythagorean theorem.

All of these ideas had been presented to me by intelligent, sincere people who had devoted large chunks of their lives to searching for a city that most reputable scientists dismissed as a fairy tale. Most of the university experts I’d approached about Atlantis had equated the futility of searching for it with hunting down the specific pot of gold that a certain leprechaun had left at the end of a particular

rainbow. Now I was starting to wonder if I’d been away from home too long—because the more of these Atlantis seekers I met, the more their cataclysmic hypotheses made sense.

Perhaps the second most famous attribute of Atlantis was its distinctive circular shape, an island city surrounded by alternating rings of land and water. At the center of those rings, the story went, stood a magnificent temple dedicated to the Greek god Poseidon. That innermost island, with its evidence of an advanced civilization suddenly destroyed by a watery disaster, was the proof that every Atlantis hunter most longed to find. Incredibly, this legendary island’s precise measurements, as well as the dimensions of the temple and the city’s distance from the sea, had been handed down from the philosopher Plato, one of the greatest thinkers in Western history. The clues to solving this riddle had been available for more than two thousand years, but no one had yet found a convincing answer. Hübner insisted that according to his own calculations, what we were about to see was close to a perfect match.

Hübner wasn’t an especially chatty guy, so we trudged silently up the slope, the only sounds coming from our feet scraping the sunbaked ground and the occasional bleating of stray goats. Finally, the incline leveled off and we looked out onto a large geological depression, a sort of desert basin enclosed on all sides. I leaned against a leafless tree and wiped sweat from my eyes.

“You remember how I showed you the satellite photo, how it was like a ring?” Hübner said, waving his hand across the panorama. “That is this place here.”

Of course I remembered. The image he’d shown me on his computer screen was like a treasure map leading to Atlantis; it was that photo that had convinced me to come to Morocco. I scanned the horizon from left to right and slowly recognized that we were standing above a natural bowl, almost perfectly round. In the middle was a large hill, also circular—a ring within a ring.

“On that hill in the center is where I found the ruins of the gigantic temple,” Hübner said. “You can check for yourself the measurements. They are almost exact with the story of Atlantis.” He sipped from his water bottle. “I would like to show this to you. Do you think maybe we should go down there?”

That Sinking Feeling

New York, New York

A

few years ago, for reasons that presumably made sense at the time, a friend who worked at a popular women’s magazine called to ask if I’d consider taking on an unusual writing assignment. Might I be interested in compiling a list of the greatest philosophers of all time and explaining, in easily digestible chunks, why their work was relevant to America’s working mothers?

Having dropped the one philosophy course I’d signed up for in college, I knew little about the subject. But easy money is hard to come by for a freelance writer, and this job sounded like a cakewalk, so I set to work contacting professors at various reputable universities and asking them to rank their top ten philosophers. To my surprise, there was no disagreement about who deserved the top two slots on the list. Every professor I phoned or e-mailed named the ancient Greek philosopher Plato number one, followed by his protégé Aristotle.

I knew a thing or two about Aristotle, since he’d been one of the final entries in the lone Aa–Ar volume of a children’s encyclopedia that my mother had purchased at the supermarket one Saturday to keep me quiet while she shopped. (I wrote many grade school papers on the differences between aardvarks and anteaters.) Aristotle’s genius

is still evident to a modern reader, and his work is very much in line with what most of us assume philosophy is. He talks a lot about ethics and logic. He was a master of classification who sorted messy subjects like language and nature into neat categories that we still use today. He’s a little dull, but “invented deductive reasoning” is a pretty impressive accomplishment for anyone to list on his resume.

Aristotle’s teacher, Plato, was in many ways his opposite. Where Aristotle’s work is dry and rational like a science textbook, Plato’s philosophy is entertaining and figurative. His writings unfold as dialogues between characters, some drawn from real life. It’s not always clear if he’s being serious or ironic. Yet Plato’s influence has been so great that the eminent British logician Alfred North Whitehead once commented—in a remark that I must’ve heard a dozen times during my reporting—that Western philosophy “consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”

What had seemed like a quickie writing assignment stretched into weeks of research as I struggled to get a grip on Plato’s engrossing but slippery ideas. One afternoon, while reading Julia Annas’s introductory survey

Plato

, I came across a sentence so striking that I had to reread it twice before its significance sank in: “In terms of sheer numbers of people affected, probably the most influential thing Plato ever wrote was his unfinished story of Atlantis.” In other words, the most impactful concept ever put forth by the most celebrated philosopher of all time was the famous tale of a lost civilization that sank beneath the waves.

That the story of Atlantis—much beloved by psychics, UFO spotters, and conspiracy theorists—should have sprung from one of history’s greatest minds struck me, to put it lightly, as a little odd. It was like hearing that Wittgenstein had helped fake the moon landings.

Around this time the Ocean extension of Google Earth was launched. The Atlantis seekers almost immediately flooded the Internet with claims that they’d

located it at the bottom of the

Atlantic near the Canary Islands. But what had initially looked like the street plan of a vast underwater metropolis turned out to be a grid pattern caused by ships’ sonars. After a few days the excitement faded. I assumed the seekers turned their attention back to more important matters, like searching for Bigfoot.

I did not yet understand that Atlantis is a virus, and that I’d been exposed.

• • •

Starting in the late 1970s, a hugely successful movie trilogy was released that changed the lives of a generation of American boys. These three tales of incredible journeys, inspired by ancient myths and conflicts that transpired a long time ago in places far, far away, were cinematic catnip for preadolescent suburban youths with overactive imaginations and limited athletic skills. Some of my fondest childhood memories are of being dropped off with my best friend at the local Lake Theater and vibrating in our seats with anticipation. It didn’t matter that the dialogue was hackneyed or that we knew good would triumph over evil in the end. Even today, reading the titles of those three film epics gives me a chill that Luke Skywalker’s adventures never could:

In Search of Noah’s Ark

,

Beyond and Back

, and

In Search of Historic Jesus

.

What made these movies, and their beloved stepsibling, the Leonard Nimoy–hosted television show

In Search Of . . . ,

so enticing was their willingness to explore what were known then as “unexplained phenomena” by straddling the worlds of history and myth. My Catholic school education didn’t allow for a lot of gray areas and ambiguities. Rather than declaring everything to be either true or false, these movies and programs left things open-ended. (

Could this thing that looks like a dirty tablecloth actually be the burial shroud of Jesus? Probably not—but maybe!

) A lot of what I watched was simply goofy—even at age ten I had doubts about anything involving Martians or

communicating with plants. But usually, by the time the credits rolled I felt an uncontrollable urge to solve some mystery of my own. With enough hours in the library and one of those cool archaeologist’s brushes, why couldn’t I find Noah’s ark or figure out the meaning of Stonehenge?

I should have known I had no natural immunity against a contagion as powerful as Atlantis, but the symptoms crept up on me slowly. Just as a couple who’s thinking about having a baby suddenly starts seeing pregnant women on every street corner, I began to notice mentions of Atlantis online or on TV. The popular notion that Atlantis had sunk in the middle of the Atlantic seemed to have fallen out of fashion. I watched a BBC documentary that argued the Greek island of Santorini had been the original Atlantis, then saw a Discovery Channel special that strongly suggested the lost city had once been located in Antarctica. Months passed. Another writing assignment took me to a banquet for people who’d achieved incredible medical results through alternative health therapies. As a conversation starter I mentioned my new interest to my tablemates and nearly started a fistfight between a homeopath and an aromatherapist. One knew beyond the shadow of a doubt that Atlantis had been in the Bahamas while the other angrily insisted that only an idiot would search anywhere but the Mediterranean.

The more I became intrigued, the more apparent it became that searching—

actively

searching—for Atlantis, a discipline sometimes referred to as Atlantology, is something of a growth industry. Using clues embedded in Plato’s dialogues, Atlantologists had variously “located” his lost island empire in Scandinavia, Alaska, Indonesia, and just about every country that touches a large body of water. A few arguments were even made for landlocked, mountainous countries such as Bolivia, which seemed a little ambitious considering that whole sank-into-the-sea aspect. According to the most thorough tally I could find, more serious hypotheses about the location of

Plato’s lost civilization had been proposed in the last ten years than in the previous twenty-four hundred, going all the way back to the days when Plato walked the streets of Athens.

Virtually all these possible sites had been found by energetic amateur sleuths. Serious historians and archaeologists, when they deigned to consider Atlantis at all, have always tended to treat Plato’s tale as a fiction invented to illustrate his complex political philosophy. At least the polite ones did. One specialist in archaeology and ancient history had written an entire book that treated the urge to find Atlantis as a sort of mental disorder.

And yet, almost universally believers and nonbelievers both agreed that Plato had done two things that made a real Atlantis seem believable. First, he embedded dozens of precise details in his story, including measurements, landmarks, and its position relative to other known places—the same sorts of particulars that have been used to find other lost cities. Second, Plato claimed repeatedly that the story was true and had been passed down to him from very reputable historical sources. This assurance only raised more questions. Was his pledge of veracity a clever philosopher’s trick to make a fantastic tale sound more realistic, or did he really believe that Atlantis had once existed? Was it possible that Plato believed the story but had been given false information? No original manuscripts of Plato’s works exist. Could his writing have been corrupted with errors over the centuries through the process of being transcribed by hand, over and over? Or had Plato, as some believed, hidden a coded message in his works that might be deciphered?

Because Plato is the only known source for the Atlantis tale, people had been debating the truth or falsity of the city’s destruction since his death in 347 BC. Academics typically gave the last word to the levelheaded Aristotle, who is quoted as having dismissed Plato’s sunken kingdom with the words, “He who invented Atlantis also destroyed it.”

Proof that the Atlantis tale was true wouldn’t just make for a great episode of

In Search Of . . .

It would also help solve some of ancient history’s greatest mysteries. The details of its sudden destruction may help explain a bizarre chain of natural catastrophes and apocalyptic famines that caused several advanced Mediterranean societies to collapse suddenly at the end of the Bronze Age. Some believed, with good reason, that the details in Plato’s Atlantis tale were closely related to stories in the Old Testament.

The virus continued to incubate. I set up an e-mail news alert for “Atlantis and Plato.” About once a week I’d receive notice that someone had devised a new location theory, as often as not pinpointing someplace like the Great Pyramid or the Bermuda Triangle.

The day after the devastating Fukushima tsunami in Japan—descriptions of which eerily echoed the “violent earthquakes and floods” that Plato claimed destroyed Atlantis—I was sitting in my office when Atlantis news alerts started pinging like a pinball machine. Evidently, someone had found the lost island for real this time, or at least serious media outlets around the world were treating the latest discovery as news.

I was torn. The logical, Aristotle half of my brain told me that it couldn’t be possible, that any search for Atlantis was bound to be the wildest of goose chases. The daydreamy, Plato half of my brain said that nothing was beyond imagining. Perhaps this was something I should look into further, I thought. I searched out a passage I’d underlined in Plato’s

Meno

, in which the characters discuss the limits of knowledge. One philosopher says to another, “We shall be better and braver and less helpless if we think that we ought to inquire than we should have been if we indulged in the idle fancy that there was no knowing and no use in seeking to know what we do not know.”

Bumper sticker translation: If you don’t ask questions, you’ll never find any answers.