Meditations on Middle-Earth (25 page)

Read Meditations on Middle-Earth Online

Authors: Karen Haber

Tags: #Fantasy Literature, #Irish, #Middle Earth (Imaginary Place), #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Welsh, #Fantasy Fiction, #History and Criticism, #General, #American, #Books & Reading, #Scottish, #European, #English, #Literary Criticism

Victorian England was inundated with fairies. They danced upon the ballet stage, pranced through elaborate theatrical productions, trooped through enormous paintings hung in Royal Academy exhibitions. The overwhelming public interest in fairies was largely a product of the Industrial Revolution and the social upheavals engendered by this new economy. As vast tracts of English countryside disappeared forever under mortar and brick, fairies took on a glow of nostalgia for a vanishing way of life. Just as interest in fairy lore reached its peak, a peculiar thing happened: fairy-stories began to find themselves moved from the parlor to the childrens’ rooms. There were two primary reasons for the sudden explosion of fairy books aimed at children. First, the Victorians romanticized the very idea of “childhood” to a degree that had not been known before—for earlier, it had not been viewed as something quite so separate and distinct from adult life. (Our modern notion of childhood as a special time for play and exploration is rooted in these Victorian ideals, although in the nineteenth century this held true only for the upper classes. Working-class children still labored long hours in the fields and factories, as Charles Dickens portrayed in his fiction—and as a child experienced himself.) The second reason was the growth of a new middle class that was both literate and wealthy. There was money to be made by exploiting the Victorian love affair with childhood; publishers had found a market, and they needed product with which to fill it. Cheap story material was available to them by plundering the fairy tales of other lands, simplifying them for young readers, then further editing the stories to conform to the rigid standards of the day—turning heroines into passive, modest, dutiful Victorian girls, and heroes into square-jawed fellows rewarded for their Christian virtues.

In his Andrew Lang Lecture (named for one of these very Victorian editors, although certainly not the worst of them), Tolkien decried this bowdlerization of the older fairy-story tradition. “Fairy-stories banished in this way, cut off from a full adult-art, would in the end be ruined; indeed, in so far as they have been so banished, they have been ruined.” Tolkien would have been discouraged indeed had he known that worse was still to come, for Walt Disney would do more damage to the tales than all Victorian editors put together. Just the year before, Disney had released

Snow White

, his first feature-length cartoon, making sweeping changes to this story of a mother and daughter’s poisonous relationship. Disney expanded the role of the prince, making the square-jawed fellow pivotal to the plot; he turned the dwarves into comically adorable (and thoroughly sexless) creatures. In this singing, dancing, whistling version, only the queen retains some of her old power. She’s a genuinely frightening figure, and far more compelling than the giggling, simpering Snow White—who is introduced in Cinderella’s rags, downtrodden but plucky. This gives Disney’s rendition of the tale its peculiarly American flavor, implying that what we are watching is an Horatio Alger–type rags-to-riches story. (In fact, it’s a story of riches to rags to riches, in which privilege is lost and then restored. Snow White’s pedigree beauty and class origins, not her housekeeping skills, assure her salvation.) Although the film was a commercial triumph, and has been beloved by generations of children, critics through the years have protested the broad changes Disney Studios made, and continues to make, when retelling such tales. Walt himself responded, “It’s just that people now don’t want fairy stories the way they were written. They were too rough. In the end they’ll probably remember the story the way we film it anyway.” Regrettably, time has proved him right. Through films, books, toys, and merchandise recognized all around the world, Disney, not Tolkien, is the name most associated with fairy-stories today.

Disney, and the imitative books he spawned, bears a large part of the responsibility for our modern ideas about fairy tales and their fitness only for small children. And not all children at that, Tolkien argues persuasively in “On Fairy-Stories.” Children, he says, cannot be considered a separate class of being with tastes all formed alike. Some children, like some adults, are born with a natural appetite for marvels, while other children, even those raised side by side, simply are not. Those of us born with this appetite usually find that it doesn’t diminish with age, unless society teaches us to repress or sublimate it. Tolkien, of course, was the kind of child who hungered for marvels and magical adventures. “I desired dragons with a profound desire,” he tells us eloquently. And yet, he notes, fairy tales had not been his only interest in childhood. There were many things that he liked just as much, or more: history, astronomy, botany, grammer, and etymology. A deeper passion for fairy-stories developed “on the threshold of manhood,” where it was “wakened by philology.” And, he adds almost as an aside, it was “quickened to full life by the war.”

I desired dragons with a profound desire

. Most Tolkien readers, I suspect, have felt that very same sentiment. I certainly did, and yet I, too, desired many other things as well; and music, not books, played a far more dominate role in my early years. A stronger interest in fairy-stories wakened, like Tolkien’s, “on the threshold of adulthood,” and was, like his, “quickened to life by war,” of a peculiar sort. Before I leave the good green hills of Tolkien’s England for my own America, I’d like to take a moment to look at war in relation to fairy-stories. Tolkien himself does not dwell on this subject in the text of his Andrew Lang Lecture, and yet (as Tolkien scholars have argued) the experience of a world at war, of evil that threatened the land he loved, informs every single page of Frodo’s journey through Middle-earth. It is this—along with the elegant framework of myth and philology on which his tale is constructed—that lifts The Lord of the Rings from entertainment into literature.

Another great fantasist, Alan Garner,

2

has written about his own experience as a child in England during World War II, and how such experience affects the writing of magical fiction. “My wife,” Garner notes, “claims to find, in recent children’s literature, little that qualifies as literature. She asked herself why this should be, after a Golden Age that ran from the late Fifties to the late Sixties. And she found that generally writers of this Golden Age were children during the Second World War: a war raged against civilians. The atmosphere these children and young people grew up in was one of a whole community and a whole nature united against pure evil, made manifest in the person of Hitler. Parents were seen to be afraid. Death was a constant possibility. . . . Therefore, daily life was lived on a mythic plane: of absolute Good against absolute Evil; of the need to endure, to survive whatever had to be overcome, to be tempered in whatever furnace was required. . . . Those children who were born writers, and would be adolescent when the full horrors [of the concentration camps] became known, would not be able to avoid concerning themselves with the issues; and so their books, however clad, were written on profound themes, and were literature. The generation that has followed is not so fueled, and its writing is, by comparison, effete and trivial.”

3

While I agree with Garner that the “tempering furnace” of war has resulted in fine works of fantasy, I’d like to suggest that mythic themes can be found in other areas of life—including the domestic sphere that has been the historical province of women. Let’s take a look at the field of magical fiction published during the twentieth century, a field that, thanks to Tolkien, expanded rapidly from the sixties onward. It is possible to divide these books into two related but different kinds of tales: those rooted in the themes, symbols, and language of myth, epic, and romance, and those rooted in the humbler stuff of folklore and fairy tales. The first category includes tales epic in scope, full of sweeping heroic adventures and battles on which the fate of worlds, or at least kingdoms, depend. The later category includes much smaller tales, more intimate in nature—stories of individual rites of passage and personal transformation.

4

Historically, epic literature was composed by men of the privileged classes, and preserved by highly educated bards, monks, scholars, and publishers. The oral folk-tale tradition, on the other hand, was a peasant tradition, and a largely female one. Even its male literary proponents (Basile, Straparola, Perrault, and the Grimms) acknowledged that the bulk of their source material came from women storytellers. What interests me here is that Tolkien’s clear preference for the first category was “quickened” by his experience of war in its most epic form: the great horrors of World War II. My own preference for the second category grew out of a different kind of war—an intimate war, a tempering furnace confined to the home front.

In the sixties, as Tolkien’s hobbit and elves set sail across the wide Atlantic, I was a child growing up in an American working-class family. My stepfather was a truck driver, often unemployed, usually drunk; my mother held the family together working two, or three, or even four jobs at once, all of them menial, underpaid, demoralizing, and exhausting. Our small household was not unique, for this was the industrial Northeast where the steelworks and the factories that had sustained the previous generations were now all closing down, one after another, and moving south. Another thing that was not unique was the daily violence in our home—violence that broke bones, left scars, and sent us children to the hospital, where jaded, overworked doctors (in those days before child abuse reporting laws) sutured and plastered and bandaged us up and sent us back home again. There was nothing remarkable in this. Neighborhood kids sported black eyes too; their fathers were also out of work. That these men were angry was something we all knew. That they were frightened is something I only later understood. In the world my stepfather had nothing, but at home he could rule as a king, and the one measure of manhood that he had left lay in his fists. My brothers and I didn’t need Hitler’s bombs to understand how Sauron came to be; we didn’t need the Third Reich to make us feel helpless as hobbits.

It wasn’t until I turned fourteen that I discovered Tolkien’s books. I began

The Fellowship of the Ring

on the school bus sometime during that year, reading with pure amazement as Middle-earth opened up before me. Culture, back then, came largely from the radio and the television, where

The Brady Bunch

strained credulity far greater than any fairy-story. But here,

here

, in this fantasy book I found reality, and truth—for ours was a childhood in which good and evil were not abstract concepts. Here, the mortal battle between the two became a tangible thing. Darkness spread over Middle-earth, corrupting everything it touched, and yet our hero persevered, armed with the greatest magics of all: the loyalty of his friends and the courage of a noble heart. I read Tolkien’s great trilogy in one gulp, and was profoundly changed . . . not, I have to add, because those books truly satisfied me. What they did was to reawaken my taste for magic, my old

desire for dragons

. But even then, in the years before I quite understood what feminism was, I saw that there was no place for me, a girl, on Frodo’s quest. Tolkien woke a longing in me . . . and then it was to other books I turned—to Mervyn Peake, E. R. Eddison, Lord Dunsany, and William Morris, searching through those magical kingdoms for a country where

I

could live.

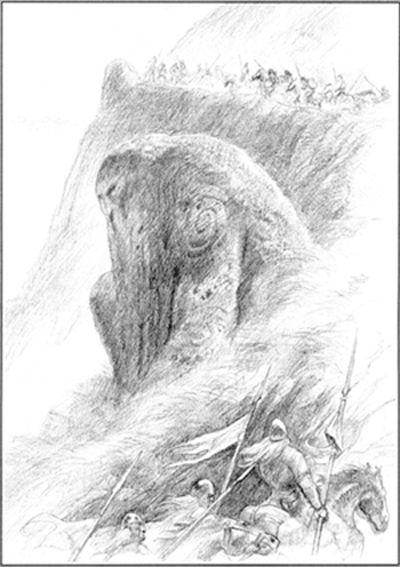

THE PUNKEL-MAN

The Return of the King

Chapter HI: “The Muster of Rohan”

Some months after I finished The Lord of the Rings, I discovered Tolkien’s

Leaf by Niggle

, a volume containing the expanded text of his essay “On Fairy-stories.” How, now, can I possibly convey the elation this slender book gave me? To understand, perhaps I must set the scene a bit more clearly. Picture a girl, rather small, quite bruised, frail of health and preternaturally quiet. Nights, at that particular time, when going home was problematic, I often spent in a secret nest I’d made (unbeknownst to anyone except a sympathetic janitor) in a hidden corner of the prop room behind my high school’s auditorium stage. Terror and exhaustion have never been known as aids to education, and so it was with laborious effort that I made my way through Tolkien’s prose, my critical faculties strained to their limit by this Oxfordian scholar. I didn’t understand all of it, not then. But I knew, somehow, this essay was for me. “It was in fairy-stories,” Tolkien told me, “that I first divined the potency of the words, and the wonder of the things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine.”

Yes, yes, yes, I

murmured, excited now, for I’d felt that too. And this: “I desired dragons with a profound desire. Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighborhood . . . But the world that contained even the imagination of Fáfnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever the cost of peril.” And especially this: “. . . it is one of the lessons of fairy-stories (if we can speak of the lessons of things that do not lecture) that on callow, lumpish, and selfish youth peril, sorrow, and the shadow of death can bestow dignity, and even sometimes wisdom.”