Meatonomics (33 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

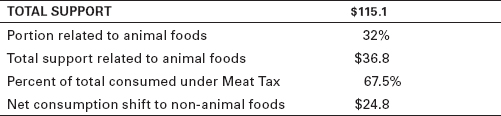

The second support change affects the gross figure of $115.1 billion in food and nutrition assistance that the USDA provides to low-income Americans. My recommendation is to exclude animal foods from nutrition assistance programs. Applying the 32 percent

multiplier introduced in

chapter 5

(consumer spending on animal foods as a portion of total retail food spending) yields a total of $36.8 billion related to animal foods to be shifted to non-animal foods.

6

In a Meat Tax economy, because consumption of animal foods is lower by 32.5 percent, excluding animal foods from nutrition support represents a net decline in animal food sales of 67.5 percent of $36.8 billion, or $24.8 billion. This figure represents 14.6 percent of the total retail sales under the Meat Tax of $169.4 billion.

TABLE C3

Effects of Excluding Animal Foods from Nutrition Support (dollar amounts in billions)

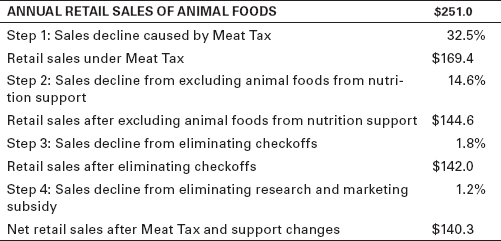

This proposal would cause annual US consumption of animal foods to fall by an estimated 44.1 percent, from $251 billion to $140 billion. It's easiest to explain this drop as occurring in multiple steps. First, with demand elasticity at 0.65, the 50 percent tax and resulting price increase causes consumption to drop by 32.5 percent (0.5 x 0.65)—yielding an initial sales decline from $251 billion to $169 billion. Next, as we saw above, excluding animal foods from nutrition support causes these sales to decline by a further 14.6 percent, eliminating checkoffs causes a further sales decline of 1.8 percent,

7

and eliminating the research and marketing subsidy causes sales to further decline by 1.2 percent. The net result is that retail sales fall to about $140.3 billion, 44.1 percent below their current level. Note that there is no particular importance in the order of these steps; the net result of $140.3 billion is the same regardless of how the steps are sequenced.

TABLE C4

Effects of Meat Tax and Support Changes on Quantity Demanded (dollar amounts in billions)

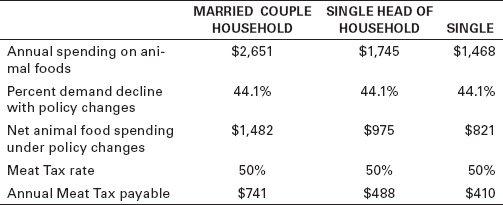

The Meat Tax will impose a new tax burden on Americans. We can calculate this burden by determining consumption levels under the Meat Tax, and then determining the tax paid by consumers at those consumption levels. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that on average, American family units spend between $1,468 and $2,651 yearly on meat, eggs, dairy, and fish.

8

Table C5

shows the Meat Tax's estimated burden on Americans by family unit type, after accounting for projected declines in consumption.

TABLE C5

Meat Tax Burden on American Family Units

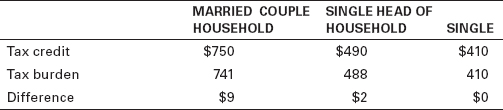

The proposal includes providing tax credits to offset the cost of the Meat Tax to individual taxpayers. Rounding each family unit's Meat Tax–related burden up to the nearest multiple of $10 to determine the appropriate credit amount, the proposed credits and projected tax relief are as shown in

table C6

.

TABLE C6

Tax Credits and Burdens by Family Unit

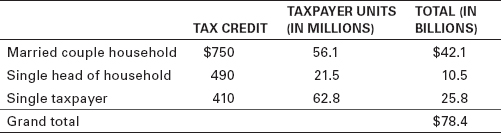

Using the Internal Revenue Service's figures for taxpayers by family unit type, the proposed tax credits would cost an estimated $78.4 billion, as shown in

table C7

.

TABLE C7

Cost of Tax Credits

9

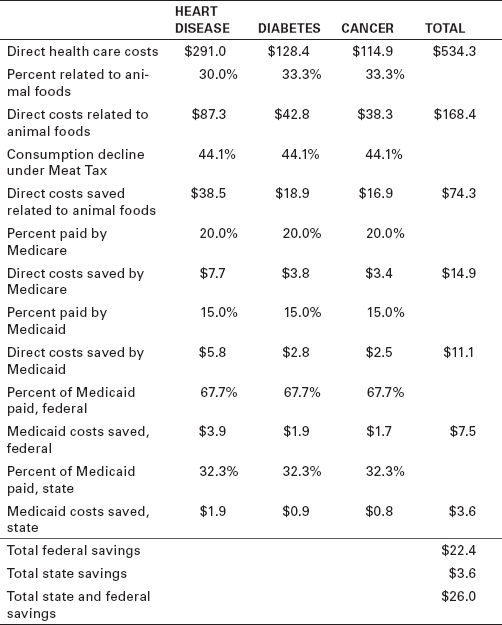

Another effect of the proposed changes is to lower state and federal expenditures on Medicare and Medicaid programs. Of all US health care expenditures, Medicare pays an average of 20 percent and Medicaid an average of 15 percent.

10

Accordingly, reductions in direct US health care costs associated with animal food consumption will lead to lower government payments under these programs, as shown in

table C8

. The federal government pays all Medicare costs and roughly two-thirds of Medicaid costs, yielding total annual federal savings of $22.4 billion. The total annual state savings are $3.6 billion. (Note that because these savings relate to gains in wellness that will be achieved only as individual eating habits lead to fewer health care problems, it may take several years of improvement in diet and health before these gains are fully realized each year.)

TABLE C8

Reduced Government Payments to Medicare and Medicaid Programs (dollar amounts in billions)

(Note that the

direct

health care costs itemized above are significantly lower than the

total

health care costs attributable to these three diseases. That's because the total costs include

indirect

costs such as lost wages, which are excluded from the above calculations as they do not affect Medicare or Medicaid.)

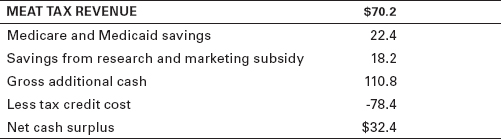

Using data from

tables C2

,

C4

,

C7

, and

C8

, we can estimate the annual impact these proposed changes will have on cash in the US Treasury. With adjusted retail sales of animal foods at $140.3 billion and a tax rate of 50 percent, the Meat Tax will generate tax revenue of about $70.2 billion. Combining this with the other estimated figures yields a total annual federal cash surplus of about $32.4 billion, as shown in

table C9

.

TABLE C9

Changes in US Treasury's Cash Flow (in billions)

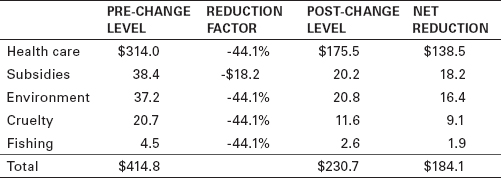

Finally, the Meat Tax and other proposed changes would greatly reduce the externalized costs of meat and dairy production. As shown in

table C10

, the total annual reduction in externalized costs is estimated at roughly $184 billion. With the exception of subsidies, all externalized costs would be reduced by 44.1 percent, which is the factor by which the policy changes are estimated to reduce consumption and hence production. Subsidies are reduced by the amount of the research and marketing subsidy proposed to be eliminated.

TABLE C10

Annual Reduction in Externalized Costs of Animal Foods Resulting from Meat Tax and Other Changes (dollar amounts in billions)

Factory Farming Practices

There is a common belief, at least among animal food producers, that technological progress in farming helps the animals whose lives it affects. Efficiency is good for economic markets, and as Dickens wrote, “A good thing can't be cruel.”

1

Like most business operators, animal farmers welcome almost any innovation that improves efficiency and boosts profits. Just as it has for the car industry, repeated tinkering to improve processes and increase outputs has yielded significant productivity gains over the past century for animal agribusiness. As noted, the last century saw a tripling in per-cow dairy production and a doubling in per-hen egg production. These efficiency gains have been driven by advances in areas like feeding, handling, selective breeding, and of course, confinement methods. Yet while humans associate innovation and efficiency with progress and improvement, the animals, if they could talk, would almost certainly disagree. This appendix explores the production methods which prevail in factory farms across the United States and are routinely used in raising hogs, dairy cows, veal calves, broiler chickens, and laying hens.