Meatonomics (27 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

In a sense, the dollar values in this book are mere

proxies

for social ills. They're measuring tools. The main problems are the underlying issues themselves, and those are the ailments this book seeks to address. This week, thousands of Americans will die from diseases

related to eating animal foods. At any moment, 1 billion US farm animals are hyper-confined in stressful conditions, and groundwater sources in one-third of US states are polluted with animal waste. Although these problems' price tags are huge, dollars are just one way of measuring the damage.

In this final chapter, I propose steps Americans can take—both individually and collectively—to alleviate the social harms caused by meatonomics. That means improving our health, fostering ecological well-being, and lowering the system's costs—both economic and otherwise—to all of us. It's a complex set of issues, and although this book views them through an economic lens, the human and humane problems—not the cash—are the real concerns. Unlike corporations, living beings are in it for a lot more than the money.

Let's start with a recap of this book's major points. First, under ever-increasing pressure to raise campaign funds so they can get elected or reelected, lawmakers reward industry donors by passing legislation that surrounds meat and dairy producers with a precious cocoon of protection. These measures include ag-gag laws, cheeseburger laws, food defamation laws, customary farming exemptions, and animal enterprise terrorism laws. Although couched in terms of defending citizens, such protections routinely favor industry over consumers. These laws make it increasingly hard to investigate, criticize, or sue factory farmers over food safety, personal injury, or animal cruelty. This legislation is also part of a legal framework that permits producers to offload most of their costs onto society. “Big business is not dangerous because it is big,” said former President Woodrow Wilson a century ago, but because of “privileges and exemptions which it ought not to enjoy.”

Second, regulatory agencies frequently favor animal food producers over consumers. The USDA promotes meat and dairy highly effectively, using government messaging to bombard consumers in a variety of media. But when it comes to acting on its stated mission to protect us through food labeling, nutrition advice, and food safety

programs, the USDA's loyalty to industry often results in confusing, misleading, and ineffective regulatory measures. The FDA has similar conflicts of interest, rendering the agency unable to withdraw animal drugs that even its parent, the Department of Health and Human Services, acknowledges are dangerous. It's become almost what former President Rutherford B. Hayes feared in 1876: “a government of corporations, by corporations, and for corporations.” The animal food industry's capture of the agencies meant to regulate it is another support beam in the structure that lets industry impose its production costs on taxpayers and consumers.

Third, animal food producers engage in a sophisticated public relations campaign to convince consumers that meat and dairy are healthy in almost any quantity and that animals are treated well. However, a deeper look at these communications—and the underlying research—finds that much of what the industry tells consumers is inaccurate and misleading. In fact, the research overwhelmingly shows that meat and dairy are unhealthy, particularly in the super-sized portions Americans consume them. Moreover, contrary to industry assertions that zero-grazing dairy cows are happy and that hyper-confined pigs love their conditions, the body of evidence shows something radically different. In fact, virtually all farm animals in the United States are raised in conditions of extraordinary stress and suffering, including routine, painful mutilation or amputation of body parts, and a lifelong denial of basic and natural behaviors.

This trifecta of lopsided lawmaking, regulatory failure, and industry doublespeak has saddled America with a set of massive, far-reaching problems in many categories. Americans are caught under the thumb of the supply-driven forces of meatonomics, and our ability to make informed, healthy choices about what we eat is heavily impaired. This combination of misinformation and artificially low prices fosters unnatural and undesirable levels of consumption. We eat more meat and dairy than any other people on the planet, and we pay for our high consumption with some of the world's highest rates of obesity, cancer, and diabetes. This gluttony hurts nature as much

as it does us. Most US farmland produces below capacity because of soil erosion related to animal agriculture, and thirty-five thousand miles of American waterways are polluted with animal waste. Our surging demand for fish has destroyed fisheries and marine ecosystems in North America and the rest of the world.

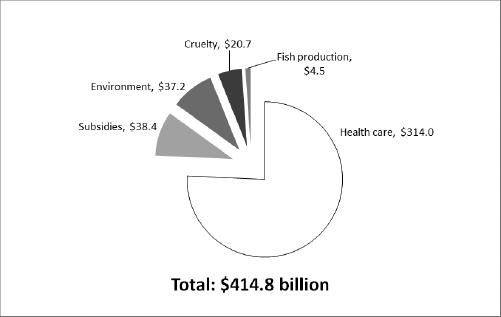

Most of us sense that something is rotten in the state of meatonomics. Polls regularly show that voters are outraged by farm subsidies and consumers are alarmed by inhumane and unsanitary conditions on factory farms. Nevertheless, there is little change in the status quo, and most of us go about our daily lives—working to pay our share of the massive financial costs that these problems cause. As we've seen, the hidden expenses of meatonomics total more than $400 billion dollars yearly. Let's revisit those costs for a moment.

The hidden costs associated with animal foods are about the same as all state and federal spending on Medicaid, or about $20 billion more than Russia's annual government budget. However you look at this number, it's huge. For a line-by-line look at how this $414 billion estimate is calculated,

see

Appendix B

.

CHART 10.1

External Costs of US Animal Food Production (in billions of dollars)

Some may question the underlying assumptions and conclude that this huge total is overstated. But rather than being on the high side, this total likely understates the actual costs for several reasons. In order to keep this figure credible and focused on the United States, I've omitted data that can't be measured (but nevertheless exist), data that are irrelevant to the American economy (but relevant elsewhere), and data that standard economic theory does not currently recognize (but arguably should, and may someday).

1

Big problems call for big solutions, so the real question is, what can be done?

I propose a three-part solution to the problems of meatonomics. First, adjust taxes to make animal foods more costly and to put cash in taxpayers' pockets. Beyond the financial boost, this change would give consumers more accurate price signals and lead to an important shift in consumption patterns. Second, restructure the USDA, clarifying its purpose to ensure that industry influence is minimized and consumers receive accurate information. And third, adjust federal support programs to reduce spending and better align financial support with policy goals. All told, these changes would lower the hidden costs of animal food production by an estimated $184 billion per year, save more than 172,000 American lives yearly, and cut our carbon-equivalent emissions by almost half each year. If it doesn't completely fix the failed market for animal foods, it's a big start with a serious impact. But before we get to the macro plan, let's start by laying out a few simple changes that anyone can make personally. To tweak an old adage: fixing the animal food industry starts at home.

“They always say time changes things,” said Andy Warhol, “but you actually have to change them yourself.” In fact, anyone can make an instant, personal change that will immediately reduce the burden of meatonomics on people, animals, and the environment. That simple shift is to consume less animal foods—or give them up altogether.

Want to lose weight? Studies find that on average, people on a plant-based diet weigh significantly less than omnivores. A 2009 research paper published in

Diabetes Care

, for example, found that after adjusting for confounding lifestyle factors like physical activity and television watching, vegans and meat-eaters had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 23.6 and 28.8, respectively (anyone with BMI over 25 is considered clinically overweight).

2

This finding led the study's authors to note the “substantial potential of vegetarianism to protect against obesity.”

3

It's hard to argue with the 18 percent difference in BMI between the two groups. That means that if diet were the only factor in weight loss, an omnivore who weighed 180 pounds could shed 32 pounds by going vegan.

Want to lower your cholesterol? Studies routinely find herbivores have far healthier cholesterol levels than omnivores. One synthesis of published papers on the subject finds that American vegans and omnivores have average blood cholesterol of 146 mg/dl and 194 mg/dl, respectively.

4

These figures are particularly important because, while the magic number 200 mg/dl is often cited as the safe level for total blood cholesterol, considerable evidence points to the much lower 150 mg/dl as the truly safe level. The Framingham Heart Study, for example, is a long-running cardiovascular study on thousands of residents (spanning three generations) of Framingham, Massachusetts. Among study participants who suffered heart attacks, more than one-third had cholesterol levels between 150 and 200 mg/dl.

5

On the other hand, no one in the Framingham study with cholesterol below 150 mg/dl ever suffered a heart attack.

If you're not ready for wholesale change, consider some of the effects of skipping animal foods just one day a week. A single American's decision to forego meat, eggs, and cheese each Monday would cut 450 pounds from the total volume of animal waste generated for the year—enough to fill a bathtub to the brim. That decision would also spare at least five land animals each year from hyper-confined lives in factories. If a family of four skips steak one day a week, according to a 2011 report by the Environmental Working Group, the reduction in carbon emissions would be like taking a car off the road for three

months.

6

There are also major health benefits in bypassing animal foods just one day a week. According to Allison Righter, director of the Johns Hopkins Meatless Monday Project, replacing four servings of red meat each Monday with nuts, legumes, or whole grains reduces one's risk of death by more than 11 percent.

7

Not long ago, nuts and other stereotypical squirrel food would have been at the top of the list as substitutes for animal-based meat. But the market for vegetarian foods is growing fast, and in the past decade, food makers have introduced dozens of tasty, healthy, plant-based meats. Today, most grocery stores carry animal-free versions of foods like salami, bologna, pepperoni, pastrami, sausage, turkey, hamburger, tuna, shrimp, calamari, meatballs, corned beef, shredded beef, barbecued ribs, hot dogs, and chicken nuggets, to name a few. If you like the taste of meat but suspect you eat more of it than you should, it's easier than you might think to eat less or give it up completely.

The same goes for eggs and dairy. Plant-based substitutes abound for milk, cheese, yogurt, butter, ice cream, and eggs. Interested in cheese that's eco-friendly, humane, and cholesterol-free? Increasingly, markets carry plant-based versions of cheddar, jack, mozzarella, feta, blue cheese, cream cheese, and others. Instead of cow's milk, there's milk from oats, rice, hemp, soy, almonds, and coconuts (my own favorite is vanilla-flavored almond milk). Another humble recommendation: coconut-milk ice cream (it comes in flavors like coconut almond chip and chocolate peanut butter swirl). Plant-based foods don't taste exactly like their animal-based counterparts, and they may take a little getting used to. But then, maybe that's part of the point.

We vote with our pocketbooks every day, and our consumption choices matter. We've seen that animal food producers use a variety of techniques to make us buy their goods in the highest quantities possible, including keeping prices low to boost demand and disseminating misleading or confusing marketing messages. Perhaps a newfound understanding of the various insidious factors that influence our buying decisions will help readers make better-informed choices. Yet, while it certainly helps for individuals to spend their dollars outside

of the animal food system, society must go even farther and reform the institutions that define this system.

Some will say it's naïve dreaming to suggest changes to one of the most powerful and intractable industrial complexes on the planet. Others have proposed reform, and others will, following the release of this volume. But maybe the constant reminders are helpful. Maybe it helps to have a working blueprint. Maybe it helps to catalog the benefits that changing the status quo can yield. At any rate, many believe society will soon be ready for changes like these—perhaps a lot sooner than we think. As civil-rights-activist-turned-congressman John Lewis asked, “If not us, then who? If not now, then when?”

The same economist who introduced externalities explained how to fix them. Arthur Pigou, a Cambridge University professor active in the first half of the 20th century, conscientiously objected to World War I and drove an ambulance rather than serving in the military. He was also a famous intellectual adversary of economist John Maynard Keynes, although their public disagreements were offset by a strong private friendship. Between ambulance trips, Pigou found time to theorize that negative externalities can be fixed by taxing the goods that cause them. A Pigovian tax adjusts the market for goods that cause externalities by raising the goods' costs and thereby reducing demand for them. Such a tax pays a double dividend by both generating revenue and reducing undesirable consumption. Ideally, the new revenue adds to—or replaces—general tax revenue and thus can be used to lower general taxes.