Meatonomics (16 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

§

Although subsidies are typically not considered an externalized cost, they are included in this category for calculation purposes because, just like external costs, subsidies artificially depress prices and increase consumption, and they impose a large social burden without providing any real benefit to most consumers or taxpayers.

Diseases and Doctor Bills

The Land of the Free, by some measures, is becoming the Land of the Sick. One in three American adults has heart disease (including hypertension, or high blood pressure).

1

One in nine has diabetes, and one in twenty-five has cancer.

2

Over the past several decades, even as advances in medicine helped eradicate most infectious diseases in the United States, we've developed a new set of afflictions: diseases of indulgence. Americans spend more per person on health care than any other people on the planet, but we're far from the healthiest. And as we'll see below, a significant part of the nearly $1 trillion in annual health care and lost productivity costs related to just three diseases—cancer, diabetes, and heart disease—is directly linked to high consumption of animal foods.

The United States isn't the only country with health problems. In a report explaining why 1 billion people on the planet are overweight and prone to disease, the World Health Organization blames reduced physical activity and “foods with high levels of sugar and saturated fats.”

3

The equation is simple: lack of exercise plus poor diet equals health problems.

But for Americans, our food choices are far from simple because of the producer-driven forces of meatonomics. As much as consumers would like to stay informed and eat what's right, we often don't get the proper incentives or information. This chapter explores the relationship between animal foods' low prices, Americans' heavy consumption of those foods, and the resulting diseases and financial costs. The idea that money is at the root of the problems in meatonomics is one of the central themes of this book. Yet, the real kicker is that financial drivers, perhaps as much as—or more than—lifestyle or dietary preference, are a key reason why Americans consume so much meat, fish, eggs, and dairy. As the Pew Commission noted in a 2008 report on

factory farming, “Animal-derived food products are now inexpensive relative to disposable income, a major reason that Americans eat more of them on a per capita basis than anywhere else in the world.”

4

The artificially low prices of animal foods encourage Americans to consume these items at levels much higher than normal market forces would dictate. Government-led marketing programs add fuel to this fire of consumption. As a result, Americans eat an average of 0.6 pounds of meat each day, or about four USDA-measured servings. While this might sound like a healthy daily ration, it's actually more than a typical adult needs—by even the most liberal measure—and more than many can safely process.

In large part because of our high meat consumption, Americans regularly exceed USDA guidelines for intake of both protein and fat. Adult males under fifty, for example, eat twice the recommended daily protein allowance and close to twice the recommended maximum of saturated fat.

5

(And that's ignoring the fact that, as we'll see, the USDA's recommended levels are artificially high and represent poor targets for healthy consumption.) People don't

need

to consume meat at these levels. But market forces motivate us to do so, and rational consumers simply follow market cues. Unfortunately, those cues are making America ill.

Consider the case of the former evangelist of ultra-high meat consumption, Dr. Robert Atkins. In 2002, the Atkins Diet's founder and chief proponent had a heart attack. Rather than let the ailing physician recover in peace, critics seized the opportunity to speak out against the low-carb, high-fat diet he had followed for years. Atkins denied his diet was to blame, instead citing a chronic infection. But when bad luck visited the doctor again the following year and he died after a serious fall, the coroner's report noted that he had a history of heart attacks, congestive heart failure, and high blood pressure—all associated with eating too much saturated fat.

6

He was six feet tall and weighed 258 pounds at death, yielding a body mass index of 35 and placing him in the severely obese category. The Atkins Diet may

not have single-handedly killed its founder and chief proponent, but it seems to have caused a number of life-threatening health problems likely to have killed him eventually.

This book is not meant to dispense nutritional advice. However, because I argue meatonomics is making Americans ill in record numbers, a few nutritional highlights (or lowlights) are necessary to show why that's the case. For starters, most of the research in meat consumption in the past several decades shows that the more of it people eat, the more likely they are to develop disease. This research is presented in hundreds of studies published in peer-reviewed journals like

The New England Journal of Medicine

and the

American Journal of Epidemiology.

(Google is a great tool—if you want to read any of the articles cited in this book's endnotes, they're easy to find.) Of course, you won't find this research discussed in the marketing communiqués issued by meat and dairy producers, and if you haven't heard it before, that may be why.

The point isn't that it's a miracle you're still alive if you've eaten meat for years. Rather, the depth and breadth of studies leave it beyond dispute that the levels at which Americans consume meat and dairy increase our incidence of disease. And this higher incidence of disease, in turn, generates economic costs that affect us all.

Take heart disease, the number-one killer of Americans, dispatching more people each year than AIDS, cancer, and car accidents

combined.

A stack of published studies taller than a quadruple cheeseburger with all the fixings establishes a direct, causal link between eating meat and developing heart disease.

7

Much of the research finds that red and processed meats carry the biggest risk of heart disease, making these the most dangerous animal foods. But a 2008 study published in the

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition

found those who eat poultry just twelve times a month are more than three times as likely to develop heart disease as those who rarely eat it.

8

A typical American eats 69 pounds of poultry per year, or about thirty servings per month.

9

Thus, this study shows that at

less than half

the amount the typical American eats each month, consumption of chicken and turkey can cause heart disease.

For those who've read that turkey burgers and boneless chicken breasts are healthier than steak and hamburger, this news may come as a shock. It turns out that

healthier

is a relative concept. Clinical studies comparing one animal food to another do show some are better than others, but that's like saying it's healthier to smoke filtered cigarettes instead of unfiltered. In fact, when studies compare the health effects of plant foods to animal foods, including fish, animal foods always lose.

10

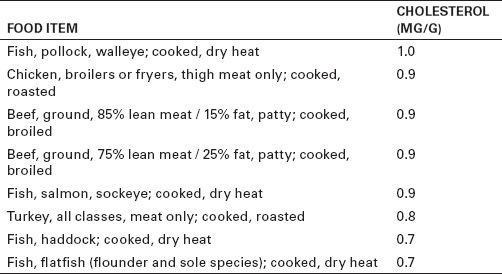

Consider dietary cholesterol, which elevates blood (or serum) cholesterol and causes heart disease.

11

Plants contain no cholesterol, but as shown in

table 6.1

, fish, poultry, and red meat contain a little dose in every forkful. In fact, bite for bite, according to the USDA, salmon and chicken contain about the

same amount

of dietary cholesterol as ground beef. Is it any surprise that cardiologists increasingly advise those with advanced heart disease to avoid

all

animal foods?

TABLE 6.1

Cholesterol Content of Select Animal Foods (mg of cholesterol per g of food)

12

Another disease closely linked to animal food consumption is type 2 diabetes, the scourge of some 34 million Americans. A 2011 study by researchers from Harvard Medical School, Harvard School of Public Health, and other leading institutions looked at the eating habits of more than two hundred thousand people. The study, published in

The

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

, concluded that consumption of just one daily serving of red or processed meat was associated with up to a 35 percent higher risk of type 2 diabetes.

13

Thus, if eaten as a steak, hamburger, hot dog, or bacon, a

single serving

of meat each day—well below the multiple servings Americans actually eat—significantly increases one's risk of becoming diabetic. As Americans eat about 50 percent more red meat than white, such research may help explain the nation's surging incidence of type 2 diabetes.

Or take cancer. Regularly eating the amount of meat in three Chicken McNuggets, about one-tenth of the typical American's daily meat intake, is enough to materially increase one's risk of developing cancer.

14

Copious research finds that meat-eaters are particularly prone to cancers of the prostate, breast, and colon.

15

Again, the studies link cancer more to red and processed meat than to white meat, and again, our nation's prodigious consumption of red meat may help explain our nation's high cancer rates.

It's not just a few outliers tapping on typewriters in the middle of a forest who have established these links between meat and disease. Four centuries ago, clergyman Thomas Fuller noted with surprising acuity: “Much meat, much malady.” Since then, his view has found support in hundreds of clinical studies from around the globe. If a single daily serving of meat can increase one's risk of developing cancer, diabetes, or heart disease, the four servings each American actually

does

eat are just asking for trouble.

Incidentally, the list of diseases clinically linked to meat consumption goes well beyond just the big three of cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. Alzheimer's.

16

Parkinson's.

17

Crohn's.

18

Arthritis.

19

Gout.

20

Cataracts.

21

Don't take my word for this. Pick any article cited in the endnotes, type the title into a browser search field, and digest the news for yourself.

But what about the important nutrients people seek from meat, like protein and iron? And what about dairy's nutrients, like calcium? How about the omega-3 fatty acids people get from fish? Or the benefits of eggs? While this chapter's purpose isn't to address the nutritional pros and cons of these animal foods, an analysis can be found

in

Appendix A

(spoiler alert: these foods aren't as necessary as you might assume).

To put Americans' half-pound of daily meat in perspective, consider how we compare to others. Per person, Americans eat nearly three times as much meat as any other culture or country on the planet.

22

We also have nearly triple the cancer rate and double the rates of obesity and diabetes as the rest of the world.

23

Of course, anyone can throw around statistics, and sometimes numbers can mislead. One might argue that because of Americans' comparative longevity, we're simply more likely than those in other countries to live long enough to develop diseases associated with old age. Still, for the nation with the world's highest gross domestic product and the sixth highest per capita income (based on purchasing power parity), factors typically associated with longer life spans, our life expectancy is surprisingly unimpressive. In worldwide longevity rankings, we're about fiftieth.

24

Most of the countries that beat us in longevity (including every nation in Europe) also have lower disease rates, meaning our high rates of diseases of indulgence stem from factors other than old age.

Another comparison offers even more clarity: how vegetarians stack up against meat-eaters. When researchers compare vegetarians to omnivores, they routinely find significant differences in health and longevity between the two groups. You don't need a mystic who can see the future for this science-based prediction—compared to a vegetarian, the typical meat-eater will die as much as ten years earlier and have twice the risk of diabetes and half again the risk of heart disease and colorectal cancer.

25

Omnivorous men have two and a half times the risk of prostate cancer as those who abstain from meat, and omnivorous women have twice the risk of breast cancer.

26

And of course, because these diseases can kill, omnivores' overall risk of death is two to three times higher than vegetarians'.

27

But what about people who have eaten a half pound of meat every day for years without any health problems? Don't years of disease-free consumption mean something? Not really. Diseases of indulgence don't

develop overnight the way infectious diseases do. The incidence of meat-triggered diseases increases with age, and many simply haven't reached the age when these illnesses develop and start to show symptoms.