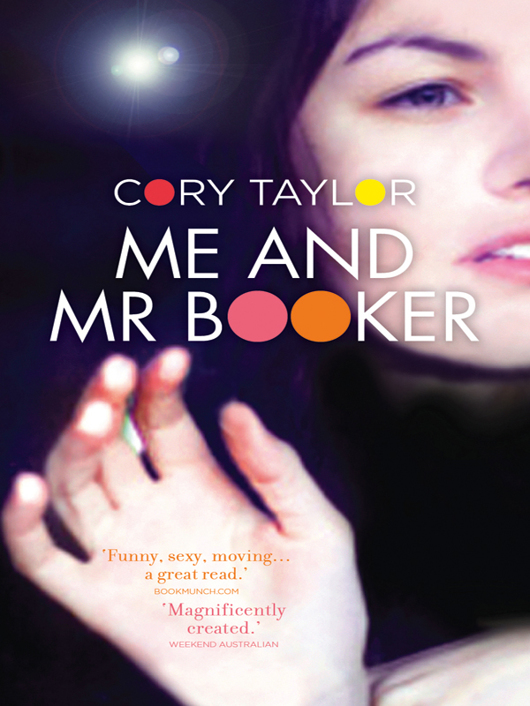

Me and Mr Booker

Me and Mr Booker

Cory Taylor is an award-winning screenwriter who has also published short fiction and children’s books. She lives in Brisbane.

Me and Mr Booker

is her first novel.

Me and Mr Booker

CORY TAYLOR

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William St

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Cory Taylor, 2010

Quote taken from T.S. Eliot’s

Sweeney Agonistes.

Quote taken from Samuel Beckett’s

Waiting for Godot.

Quote taken from T.S. Eliot’s

Four Quartets.

Quote taken from Philip Larkin’s

This Be the Verse.

Copyright © Faber and Faber Limited and the authors’ estates.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in Australia by The Text Publishing Company, 2011

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Susan Miller

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

eISBN 9781921834189

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

| Author: | Taylor, Cory, 1955- |

| Title: | Me and Mr Booker / Cory Taylor. |

| Edition: | 2nd ed. |

| ISBN: | 9781921758973 (pbk.) |

Dewey Number: A823.3

To Ev

‘You love the place you hate, then hate the place you love.’

Terence Davies

Contents

it’s lovely down in the woods today

we can’t go on. we must go on.

you take the high road and i’ll take the low road

absence makes the heart grow fonder

bye baby bunting, daddy’s gone a-hunting.

love letters straight from the heart

Everything I am about to tell you happened because I was waiting for it, or something like it. I didn’t know what exactly, but I had some idea. This was a while ago, after I decided that a girl is just a woman with no experience. I know what Mr Booker would say on the topic of experience. He would say what you lose on the swings you gain on the roundabouts.

First of all there was the question of my age. I was sixteen when I first met Mr Booker, which can be young or old depending on the person. In my case it was old. I started to feel old when I was about ten, which was about the same time my parents decided they had wasted their chances in life. I knew this because they told anyone who would listen, and this included me. I think disappointment was something I inherited from them both, along with their wavy hair and their table manners. In particular I think it was Victor who taught me at a young age how to lower my expectations.

If you didn’t know him you might have thought my father was all right; pompous and opinionated but a lot of men are like that and people put up with them. There are worse things than pompous and opinionated. Even I thought he was all right until I was old enough to know better. After that I saw Victor for what he was. Poison. Once you knew that about him you knew to steer clear. You don’t hold your hand out to a rabid dog, not unless you want trouble.

Then there was the question of the way I looked, which I’d started to notice had an effect on people. I wasn’t pretty, I was too pale and sad-looking, so it wasn’t my face. But there was something in the way I appeared to people, and I’m really talking about the men married to my mother’s friends, that made them stare. It had to do with whatever it was I was waiting for. I knew that even before they did, and that was why they liked me, and liked to kiss me on the cheek when they said hello. The ones who had children also liked me to babysit for them so they could drive me home afterwards. I didn’t mind. They were nice men. They talked to me as if I was a friend and no one tried anything, except the classical guitar teacher who was Italian, so I stopped minding his kids and gave up guitar lessons.

At school I was an average student. There was only one class I really cared about and that was French. Jessica, my mother, had already decided I was going to the university after I finished school to study to be a teacher like she was, but I didn’t want to do that. The only reason I liked French was that Mr Jolly was our teacher and all I really wanted to do was stare at Mr Jolly and listen to him reading out French vocab lists for the rest of my life. But I didn’t tell my mother that. I told her I would wait and see what my options were before I made a decision about my future.

‘You can be whatever you want to be,’ she said. ‘As long as you set your mind to it.’

Which was strange coming from her because all she’d done was throw away the best years of her life on a lost cause like Victor. Not that I needed to tell her that—she knew it better than anyone. That was the trouble with my mother. She wanted to think she could stop me from making the same mistakes she’d made but deep down she was a believer in fate.

So whenever she started to tell me how much potential I had I told her to stop because she was making it sound like I was holding myself back on purpose, which wasn’t true. What I was doing was waiting, like I said before.

Also I was dreaming about leaving her, which I didn’t tell her either because it would have made her sadder than she already was. My mother was at a pretty low point and she didn’t want to be on her own. I knew that without her having to say it. It was there in the way that she looked sometimes, as if her whole life people had been leaving her and I would be next.

‘What would I do without you?’ she said.

I told her there was no point in asking me that because it was a hypothetical question. But it didn’t stop her.

I also think that what happened had a lot to do with the kind of place we lived in then, which wasn’t a city but it wasn’t the country either. It was a kind of no-man’s-land, a town miles from anywhere that mattered, or that had any kind of smell. And everyone in it was like me, trying to move on and start something, anything at all, even if it was almost certain to go bad.

That was why, at the end of that first summer, I was in Sydney at the Five Ways Hotel waiting for Mr Booker when I should have been in school.

Mr Booker had told me he was going to leave his wife and come to Sydney to be with me. And I believed him, because of the way he said it. It was a feverish February night and he was sitting next to me in the dark outside on the terrace with his hand on my bare arm.

‘Why don’t we just run away,’ he said. ‘Somewhere where they won’t find us.’ And then he laughed, not because he wasn’t being serious but because he was drunk. So was I. I took another taste of his whisky and felt the sting of it behind my eyes. Everything in my mother’s garden started to swim.

And that’s the other thing I need to mention, which is that everybody we knew in that town drank too much. It was like nobody could get through the day without a drink.

I had met the Bookers in November at the start of the summer. I’d just finished exams and had one unpromising year of high school left. They came to a party at my mother’s house. My father was gone by then. He was living on the other side of town in a kind of motel. Every time I visited him he showed me his rifle. He kept it wrapped up in a blanket and hidden at the back of his wardrobe. He said it was to shoot rabbits with but I don’t think he really knew that for sure. He just liked to have it. It showed that he still had some surprises in store for everyone. My mother said he was planning to turn the gun on her some day.

‘He’s crazy enough,’ she said.

Not that he had ever hurt her, apart from that one time when he broke her arm and my brother Eddie had to drive her to hospital and wait for two hours while she had X-rays. My brother believed her when she told him it had been an accident. She said she’d fallen and caught her arm on the edge of the desk.

Eddie went to New Guinea after that. As far as I knew he was working on an oil rig. My mother wrote to him every week but he never wrote back.

I used to wonder what my mother saw in Victor, back in the early days before they had Eddie and me. Of course he was a lot thinner then. She had a photograph of him, taken just after they were married, standing on a street corner somewhere in a suit and tie and staring into the camera with a sly smile on his face. He was handsome in a hollow-cheeked kind of way. I used to take the photograph out of the album and stare at it. I couldn’t believe that Victor and the man in the photograph were the same person. It was impossible to know which was real: the thin man or the heavy one, the smiling youth or the middle-aged nutter. My mother must have had the same problem, I decided. She must have fallen in love with one man then discovered he was actually someone completely different.

‘He was all right until Eddie came along,’ she told me once. ‘After that he panicked.’

It is hard to overestimate how much my mother relied on parties. They got her through the weekends, because otherwise the time stretched out in front of her every Friday night like a dusty road down which nobody ever came. My mother was a country girl from a place where there were no trees and no neighbours and she knew how it felt to crave company the way a starving person craves food.

She was also catching up from years of having to stop seeing people if my father didn’t like them. Victor had deprived her of a lot of friends. Now what she did was send the word out all week that everyone was welcome to come over for dinner Saturday or lunch Sunday, and bring whoever they wanted. That way there were always new people turning up who we’d never met before, people like the Bookers.

The Bookers came because Mrs Booker had met my mother’s friend Hilary at the butcher’s shop where they were waiting to buy German sausages. Hilary was from Scotland, so she knew it was hard, she said, when you first moved to a new country and didn’t know a soul. Her problem child Philip was in the same year as me at school.