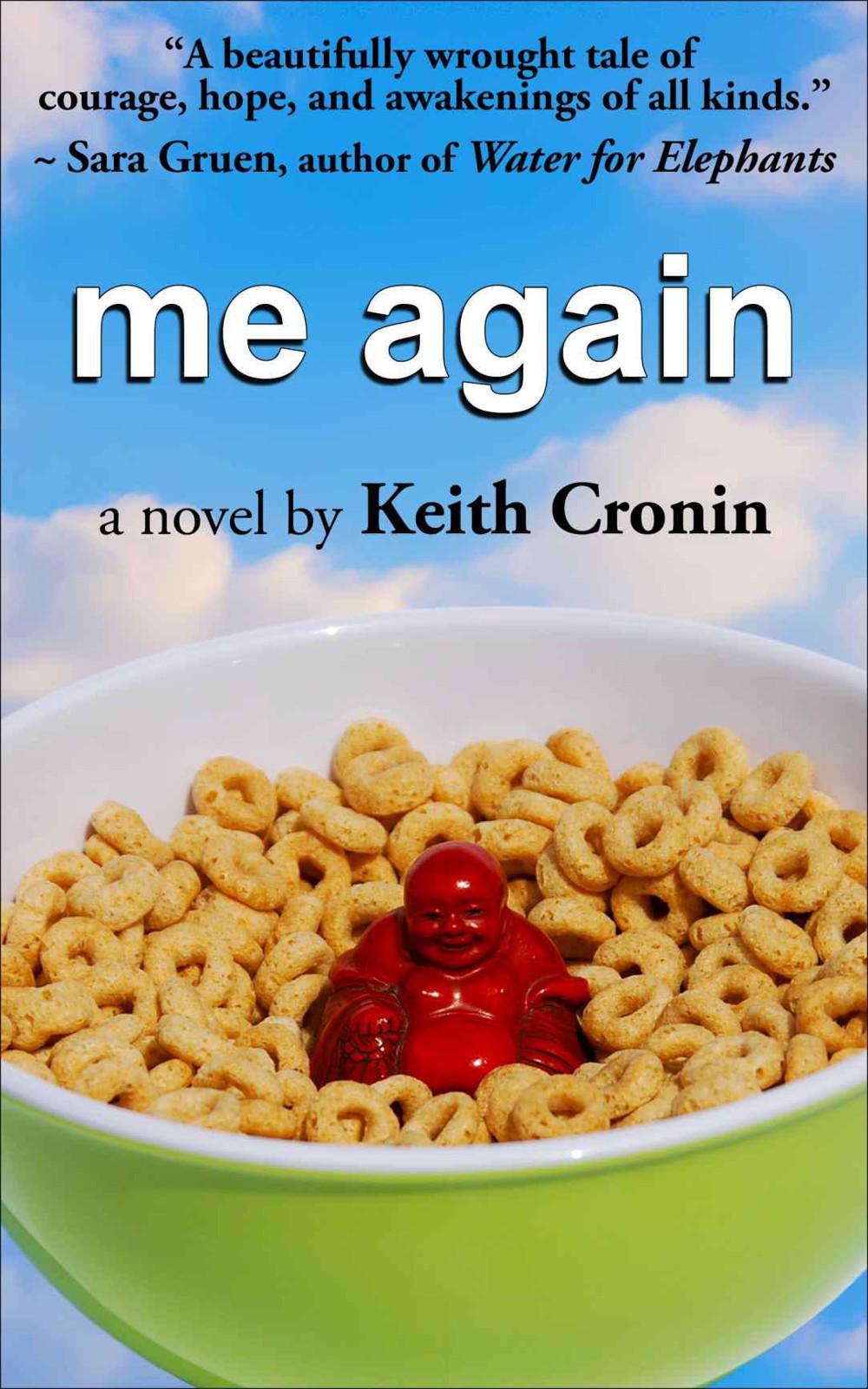

Me Again

Authors: Keith Cronin

Tags: #Fiction, #relationships, #sara gruen, #humor, #recovery, #self-discovery, #stroke, #amnesia, #memory, #women's fiction

Me Again

a novel by

Keith Cronin

Praise for Me Again

“A beautifully wrought tale of courage, hope, and awakenings of all kinds.”

~

Sara Gruen

, author of

Water for Elephants

“Heart and humor are inseparable in Keith Cronin’s engaging debut.”

~

Susan Henderson

, author of

Up from the Blue

“A work that will make readers laugh and think.”

~

Lauren Baratz-Logsted

, author of

The Thin Pink Line

“Cronin’s debut is an engaging read, utilizing an affable tone and ample humor to temper subject matter that could easily fall into melodrama. The novel shines when navigating the complex interpersonal relationships Jonathan has been thrown back into, as he gets to know not just the family he’s unable to remember, but also the man he used to be.”

~

Kirkus Reviews

“Me Again is a ‘leave me alone, I’m reading’ kind of book.”

~

Bibliophiliac

“Cronin has a gentle sense of humor that seems effortless.”

~

Book Club Classics

“A funny, sad, sweet, poignant and heartfelt novel that I can’t recommend highly enough.”

~

Stephanie’s Written Word

“Cronin is such a talented writer; it astounds me that this is his debut novel.”

~

Jenn’s Bookshelves

“Me Again will touch your heart and your funny bone.”

~

Blogcritics.org

“Cronin has a wonderfully down-to-earth, engaging style.”

~

Book Reviews by Elizabeth A. White

“Me Again encompasses the three H’s of exemplary fiction: humor, heart and honesty.”

~

Jocosa's Bookshelf

Watch the Book Trailer on YouTube:

http://youtu.be/FAooOPnkuKA

There are two births: the one when light

First strikes the new awakened sense;

The other when two souls unite,

And we must count our life from thence,

When you loved me and I loved you,

Then both of us were born anew.

~ William Cartwright

It seems to be a rule of wisdom never to rely on your memory alone, scarcely even in acts of pure memory, but to bring the past for judgment into the thousand-eyed present, and live ever in a new day.

~ Ralph Waldo Emerson

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

I

WAS BORN ON A TUESDAY MORNING. It was a difficult birth, because I was thirty-four years old.

I opened my eyes, and saw a long bar of blue-white light. It hung directly over me, making me realize I was lying on my back. Looking into the light made my eyes hurt, so I closed them, welcoming the darkness. But then it seemed particularly important to see that light again, so I reopened my eyes, blinking repeatedly to adjust to the glare.

I became aware of movement. A blurry female figure clad in white entered my view on one side. I lay staring at her, instinctively trying to blink her into focus, but with no success. Suddenly she drew closer, leaning down over me. For a brief moment our eyes met. Then I blinked.

“Jesus,” she said. The name sounded familiar.

She disappeared from view, and I realized that I couldn’t raise or turn my head to try to locate her. In fact, the only thing I could feel – or move – was my eyes. I had a vague sense that this was not good.

Although she was out of my sight, I could hear her. She was speaking, a rapid stream of words I wasn’t quite able to follow. Other voices joined in, overlapping each other in conversation, and the name Jesus came up repeatedly.

I formed my first conscious thought:

I must be Jesus

.

The voices grew louder, and several faces entered my field of vision, looming over me.

“He’s awake.”

“That’s impossible.”

“Jesus.”

“He heard you – look, he’s looking at you!”

“Get a flashlight.”

I felt fingers touch my face – I suddenly became aware of

having

a face. A moment before, all I had was eyes. Now I had a forehead, a cheek. I took a breath, discovering a nose, a mouth. My world was growing.

Then a beam of light drilled into one of my eyes, hurting me. I made a sound.

It wasn’t a word. For some reason, I couldn’t speak. I wanted to – I understood what the faces surrounding me were saying – but I couldn’t manage to form any words in response.

I made another sound.

“Jesus.”

No, that wasn’t the sound I made – that was the response my sound elicited from the blurry woman in white. With her were several other blurry women, some in white, some in pale colors.

“He’s tracking the light. See?”

Again the light stabbed at my eyes, making me blink and look away.

“It’s too bright for him. Use your finger.”

The caustic beam was extinguished, and now a woman in green held a finger in front of my eyes, moving it back and forth over my face. I tried to look past her finger, wanting to establish eye contact, to find some way of communicating with her. But the wagging finger kept distracting me.

I began to feel annoyed.

I’ve come to believe that annoyance is probably one of the first emotions each of us experiences. Think about it: the medical profession has adopted some pretty abrasive ways to greet the newborn, whether it’s spanking their bottoms, clipping their umbilical cords, or wagging fingers in front of their faces. To me it’s no wonder babies cry so much – look at the indignities to which they are subjected the moment they emerge. You’d think they could come up with more pleasant ways to welcome a new arrival.

At any rate, it eventually occurred to me that if I made an effort to watch the woman’s finger, perhaps she would stop waving the damn thing in my face and simply talk to me. That was what I wanted most of all, for people to stop talking

about

me and start talking

to

me.

With some effort, I forced my eyes to follow the motion of her finger.

“Whoa,” the woman said succinctly. I tried to answer, but again only succeeded in emitting a sound – something guttural and raw.

The woman looked at me for a long moment. Then she turned and spoke. “Beth, get Doctor Spence on the phone. Tell him to get his ass up here, stat.”

It’s hard to explain the effect this woman’s last remark had on me. The word “doctor”... well, it triggered something. It made me for the first time stop to wonder where I was. With that word came the realization that I was in some sort of medical facility. A hospital, perhaps. This meant I was sick, or that something had happened to me. Something bad.

Dr. Spence would confirm my suspicions.

“Well, look who’s awake,” a male voice bellowed. A man came into view, holding up one fist over my face. Just as I realized what that fist held, a shaft of light shot into my head. I closed my eyes and groaned, the sound foreign and ugly.

A woman spoke. “The penlight bothers him. But he followed Karen’s finger. We all saw it.”

This prompted the man to repeat the finger-in-my-face routine. Eager to see this game end, I did my best to track the movement of his finger with my eyes.

“Well, I’ll be,” the man said. “He’s responsive.” He began to scribble something on a clipboard.

I decided the time had come to assert myself. Okay, maybe that’s stating the case a bit grandiosely. But I wanted somebody to talk to me.

I made my sound – the only sound I seemed capable of making – as loud as I could.

This got their attention.

The man put his clipboard down and stared at me. Leaning in close, the man said, “Mr. Hooper, I’m Doctor Spence. Can you hear me?”

I wanted to say yes. I formed the word in my mind. Then I tried to send that order to my mouth. But I couldn’t seem to remember how to make my mouth do what I wanted. So I made my sound again. I kept it short this time, truncating the groan to a brief grunt.

“Jesus,” the now familiar female voice said.

Apparently my name was Jesus Hooper. But somehow that didn’t seem right.

The man – Dr. Spence – spoke to me again. “Mr. Hooper, I want to make sure I understand you. So I need to make sure you understand me. I know you can’t talk right now – there’s a reason for that, and I’ll explain it to you in a moment. But can you... well, can you grunt for me again?”

Now we were getting somewhere. I quickly issued a grunt, drawing gasps and nervous laughter from my audience.

Dr. Spence hastily jotted something on his clipboard. “That’s excellent, Mr. Hooper – really excellent! Now, let’s see if we can take it a step further. Let’s see if you can answer yes or no. How about if we say one grunt means yes, and two means no? Do you understand?”

But I didn’t. Those words he had used –

one

and

two

– plunged me into confusion. The words were familiar, but I couldn’t remember what they meant. I

almost

knew, but couldn’t quite summon the information. Silent and confused, I stared at the doctor.

He nodded, then said, “Do you understand what one and two are? If you do, then try to grunt for me. If you don’t, well, just remain silent.”

I did as I was told. The only sound in the room was some softly beeping medical machine.

“Tell you what,” Dr. Spence said, “let’s try switching things around. I’ll ask it a different way. If you understand what one and two are, stay silent. But if you don’t understand, please grunt.”

My grunt drew more chatter from my onlookers.

“Okay, Mr. Hooper, that’s great. Just great. Now we’re making some progress. How about we skip all that one and two stuff, and try something a little easier? If I ask you something and the answer is yes, go ahead and grunt. If the answer is no, you stay silent. Do you think you can do that?”

I grunted. I was becoming an old pro at this stuff.

“Excellent. Okay, Mr. Hooper. I’m going to explain a little about what happened to you, and where you are. Would you like that?”

I felt the grunt I emitted was particularly enthusiastic.

“Okay,” the doctor said, “let me see how I can sum things up. You had a stroke, Mr. Hooper, and that stroke put you in a coma. You remained in that coma for a little more than six years. Now, because you’ve been in a coma so long, your body probably can’t move – you may not even feel your body right now. That may change, but we’ll get to that.”

Dr. Spence paused, rubbing his face with his hand. “The even more important thing is that, well, how should I put this? A stroke can do things to your brain. It can change things. It’s likely you’ll have forgotten some things. Maybe a lot of things. You know, like what one and two mean – things like that. A stroke can produce substantial changes in your brain, so I want you to understand that.”

The doctor looked at me, trying to read my expression, which made me realize I couldn’t really feel anything beyond my face. I seemed to be all eyes, nose, and mouth, emerging like an island from some murky pool, taking in air and light while the rest of my body drifted unseen below the surface.

The man’s voice brought my attention back to him. “Mr. Hooper? That was a lot of information I just dumped on you – I apologize. Let’s back up for a second, and see how well I’m getting through.” Turning to the others who surrounded my bed, he said, “The rest of you chime in, too, in case I forget anything. But go slow – we don’t want to overwhelm him.” Once again I was being talked

about

, not

to

. It was something I would learn to get used to.

“First, let’s sit him up so we’re not all hovering right on top of him.” A mechanical whirring slowly changed my view, elevating my upper body into a sitting position. I couldn’t feel my body bending, but the ceiling swept out of view, and I found myself facing Dr. Spence and several women in medical pajamas, crowded into a small room that my bed nearly filled.

A lengthy dialog of questions, grunts, and silent pauses then ensued. I’ll spare you a complete transcription – it’s an awkward read – but here’s a summary of some of the highlights:

Did I know what a stroke was, what a coma was, and what aphasia was?

Yes, yes, and no. Aphasia had to be explained to me. According to Dr. Spence it was becoming clear that I was at least partially aphasic – this meant my language abilities had been impaired. Although it appeared that I could understand the words I heard, I wasn’t able to form language to reply. It wasn’t that I was mute; I could make sounds. But I couldn’t arrange these sounds to make sense. Spence told me things could be much worse – that some stroke victims couldn’t understand anything people said to them. And he tried to reassure me, telling me that my condition was not necessarily permanent. I would have felt better if he hadn’t bothered to use the word

necessarily

to qualify that statement.

Was I in any pain? Could I move any of my limbs?

Nope and nope. The former was a relief, but the latter was deeply unsettling, particularly now that I could see the unmoving shapes of my feet under the blanket that covered them. And my hands, veiny and pale, were completely unfamiliar. I could not will them to move, which made them very hard to look at. Instead I focused on the people talking to me.

Here was a biggie: did I know WHO I was?

They asked me this first as a yes-no, and then got clever by saying several different names, and telling me to grunt if I recognized my own. Sort of an auditory police lineup, but pretty effective.

Upon hearing it, I did recognize my first name, and duly grunted. Turns out I was

Jonathan

Hooper, not Jesus. But this Jesus was familiar, and apparently the guy was a fan of mine – the phrase

Jesus loves me

kept coming to mind.

Did I understand that I had been unconscious for six years?

I remained silent, baffled by the concept of “six years,” and worried about the emphasis they seemed to be placing on the question. A quick volley of related questions led my interviewers to determine that my absence of math skills seemingly extended into a lack of understanding of other quantitative measurements, such as years, months, and so on. But I did seem to get the difference between big and small, and was beginning to grasp that I had been asleep a much bigger amount of time than was considered normal or good.

Trying to convey to me the actual length of my coma was a challenge for the group surrounding me, who tried explaining that I was now thirty-four, which of course was not helpful. Then one nurse had an inspiration, and ran to get her purse. When she returned with it, she extracted her wallet and shook it, spilling out a lengthy accordion of plastic-encased credit cards and photographs that dangled almost to the floor. Leafing through them, she selected a photo and held it up for me to see.

“This is Megan – my daughter – when she was a newborn, just a couple of days old. This picture was taken around the same time you had your stroke. Do you understand?”

My grunt indicated assent. The tiny infant had the wrinkled misshapen look that can only be found appealing by blood relatives. My aphasia saved me from having to come up an obligatory compliment denoting the beauty of this human-raisin hybrid.

The nurse shuffled through more folds of her extensive collection, saying, “I just got these back from the Fotomat.” Finally locating the desired photo, she leaned over me once again, displaying a new image for my perusal.

“This is Megan now,” the nurse announced.

No grunt from me. This time I managed a full-on scream.