Mayday Over Wichita (19 page)

Read Mayday Over Wichita Online

Authors: D. W. Carter

âFair-Mark Committee, 1967

377

Despite the lengthy process, the victims eventually received their settlements, though most were clearly disappointed. Cora Belle Williams of 2048 North Piatt, who was thrown across her living room by the impact of the crash, filed the largest suit for $235,000. Her claim was settled for $27,500 minus $5,500 for attorney fees.

378

George Meyers and his wife, Palestine, spent fifty-eight days in the hospital, suffering from burns after barely escaping their home with their two daughters: three-year-old Debbie and seven-month-old Donna. They became even more depressed, however, when they attempted to claim the full $1,000 in temporary relief allocated to them by the air force and received only $250 instead. Their attorney, G. Edmond Hayes, later filed an optimistic $132,000 lawsuit for damages. Three years later, they settled for $45,000, one of the largest settlements.

379

Others, too, received less and lost much as a result of the crash. The amounts paid out showed little homogeneity. They were imbalanced and, as some felt, illogical. The largest amount awarded for a single death was $14,000.

380

The smallest relief granted for the death of a child was $400 and for the death of an adult, $701.33.

381

The loss of one's home or property, in most cases, paid more than the loss of a loved one.

Two adults and three children burned to death inside of 2053 North Piatt: Albert L. Bolden (twenty-two); his wife, Wilma J. Bolden (twenty-four); Denise M. Jackson (six); Brenda J. Dunn (five); and Leslie I. Bolden (nine months). The final settlement for the loss of the Bolden family was $28,059. Their attorney fees were $5,611.

382

Harvey Dale lost his wife, their newly adopted two-year-old daughter and his home. He sued for $67,000, ending up with only $36,840.38âa ratio of fifty-five cents on the dollar.

383

Laura Lee Randoph, Earl S. Randolph and Ethel McCormick handled the estate for Tracy Rachelle Randolph (five) and Mary Daniels (fifty-six), receiving a total of $18,175 for loss of their lives, property damage and funeral expenses. Attorney fees were $3,800.

384

Six people died inside of 2041 North Piatt: Emmit Warmsley Sr. (thirty-seven), Laverne Warmsley (twenty-five and with child), Emmit Warmsley Jr. (twelve), Julia A. Maloy (eight) and Julius R. Maloy (six). A total of $28,557 was awarded for their deaths. This sum also included property damage and funeral expenses. Their attorney fees were $5,961.

385

Henderson Kye, after losing his wife, Ella, when she suffered a stroke from the trauma of the crash, filed a claim for $25,215.40. Instead, he was given $2,500 for the death of his wife. His attorney fees were $500.

386

Alvin T. Allen and his family received $8,000 for personal injuries and property damage. Their attorney fees were $3,300.

387

Out of the thirty personal and property damage suits filed against the U.S. government and Boeing, Maxine C. Straughter received the lowest settlement of $100 in a suit originally asking for $2,500 in property damage. Her attorney fee was $20.

Margaret Daniels received $19,516.21 for the loss of her husband, Claude L. Daniels (thirty-two). Twenty-two-year-old James L. Glover, fast asleep when the KC-135 crashed and poured fiery jet fuel into his bedroom, probably never even woke up. His parents, James and Maxine Glover, residing in Detroit, Michigan, were awarded $14,985.53 for his death and other damages.

388

Joe T. Martin, after suffering in agony while watching his two sons burn to death in their front yard at 2031 North Piatt, would find no comfort in his settlement. Although they filed a suit for $87,483, Joe and his wife, Lucile Martin, were given only $36,000 for the loss of their home and sons, Joe T. Martin Jr. (twenty-five) and Gary L. Martin (seventeen).

389

Joe was laid off from Boeing a short time later and was unable to “face the music,” as he put it. The Martins eventually moved back to Boonsville, Arkansas, where they buried their sons.

390

“Every time they burn down a shack in Vietnam they pay for it,” said Clarence Walker. “I'm supposedly an American citizen, but they've made no restitution about my house.”

391

Clarence and his wife, Irene, leapt from their burning home through a bathroom window and a back doorâescaping death but sustaining multiple injuries in the process. They received $25,000 for personal injuries and property damage; $5,000 went to their attorney.

392

“My sores have healed, but I don't know when my soul will,” lamented Mrs. Walker after the settlement.

393

At last, on January 11, 1968, Congressman Shriver received a phone call from an air force colonel who conveyed the final settlement of the claims.

394

The thirty main lawsuits filed against the air force, seeking just over $1 million in relief and spanning over three and a half years, ended with the government paying $413,250 for loss of life, property damage, funeral costs, injuries and medical bills for all. There were also another 125 Wichitans who filed damage claims against the government outside of court that were settled for $212,000.

395

A claim of $14,138.83 by the Gas Service Company for damage to “gas meters, regulators and reimbursement for repair costs, labor and materials,” and one of $12,936.04 by the City of Wichita for property damage, equipment, salaries and material were included in the final numbers.

396

An alarming twenty-five out of the twenty-seven claims against Boeing, the codefendant with the U.S. government, were dismissed in 1968âwith neither the U.S. government nor Boeing ever taking responsibility.

397

As was noted in the

Wichita Eagle

, “The government agreed to the settlements without admitting liability or fault in any of the cases.”

398

Fault or no fault, these were considered final settlements, leaving no avenues for future lawsuits stemming from the crash.

In the end, several claimed the air force should have settled the claims quickly and for their maximum amount; a few claimed the air force deliberately delayed the process in order to decrease the amounts or to sidestep paying the settlements altogether; others claimed it was the court system that was at fault; some claimed that, if it were not for the courts, nothing would have been settled; many claimed the process might have gone quicker if the greedy lawyers had not wanted a larger percentage; and most were just plain angry. They didn't know who to blame, but no matter their opinions, one truth remained: all were dissatisfied. “No crash need leave the wake of dissatisfaction and the protracted disruption of lives,” wrote Cornelius P. Cotter, “that has characterized the federal government's response to that which occurred in Wichita, January 16, 1965.”

399

The final settlements were at best pyrrhic victories. Nobody won.

F

AMILIES OF THE

A

IRMEN

Four widows, ten children and countless friends and family of the airmen would never see their loved ones return home that Saturday. And whereas the victims on Piatt Street would at least receive some relief, although not much, the same was not true for the families of the servicemen killed. On the morning of Sunday, January 17, 1965, Jeanine Eileen Widseth heard a knock on her front door at base housing located on Clinton-Sherman AFB. Grieving from the loss of her husband barely twenty-four hours before, she reluctantly answered. Standing before her was an air force colonel in his dress bluesâpressed, polished and adorned with medals. He had visited her the previous day, accompanied by a doctor and chaplain, when they broke the heart-wrenching news of her husband, copilot Gary J. Widseth's death. Now, the colonel had even more tormenting news for Jeanine that she would never forget.

At first, he offered his condolences again and handed her a check for around $3,000. He explained it was to help pay her bills and make any adjustments that she needed to after the loss of her husband. But just before walking out the door, the colonel said quietly, “Don't even think about suing.”

400

She never saw him again. Jeanine, as she remembered, was certainly not thinking about suing the air force at the time. Her world had just come crashing down, and as a widow with small children, she had much more pressing concerns. Forty-eight years later, however, she recalled how she thought it was a military rule that she could not sue the air force for her husband's death, so she never tried. Even worse, her husband's death remained an open wound in her life. Jeanine never remarried.

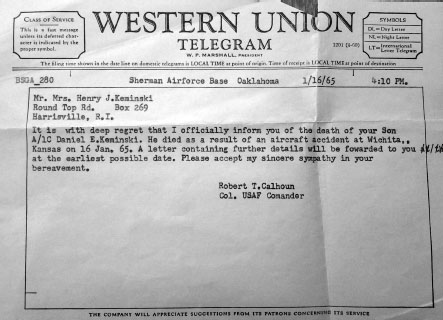

Irene Huber (Kenenski) came to loathe the insufferable memories of January 16, 1965, and the deafening silence afterward. She was nine years old when her brother, A1C Daniel E. Kenenski, assistant crew chief, died aboard Raggy 42. She recalled coming inside their house in Rhode Island after shoveling snow with her father that morning. As soon as she entered, she found her mother crouched down on the floor sobbing with the telephone in her hand. While the wet snow falling from her coat began to form melted puddles on the kitchen floor, she stood in shock, helplessly watching her mother cry over the news that Danny was dead. A Western Union Telegram from the air force carried the shattering news.

They were never told why the plane crashed and had “no information at all,” said Irene.

401

And like Jeanine, their family was instructed that a lawsuit would not be an option.

The Kenenski family was notified of Danny's death via this Western Union wire sent by the air force.

Irene Hubar (Kenenski)

.

Neither Jeanine nor Irene (and it can only be assumed, the other families), for reasons unknown, was ever given the Collateral Board Investigation Report that explained what happened to their loved onesâfurther proof that the tragedy, grief and dissatisfaction with the outcome of the Piatt Street crash extended far beyond Wichita. Families across the United States, divided by race, socioeconomic status and location, still mourn every January 16, as they have done for nearly half a century. Their afflictions were, and remain, many.

17

THE LONG-AWAITED MEMORIAL

The only people it will die with will be the ones who watched it on the news

.

âSurvivor, January 16, 1985

402

The victims of the Piatt Street crash would wait forty-two years before a memorial was named in their honor. In this case, justice took longer than the biblical account of the Children of Israel's exodus from Egypt, as they sojourned in the wilderness of the Sinai desert for forty years before entering into the Promised Land.

403

It took longer than the time needed to build the great Panama Canal, uniting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, which, after several attempts, was completed in nearly thirty-five years.

404

It even took longer than the decades needed for policies on race and equality to begin shifting in the U.S. following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. When chatter began about the possibility of a memorial, blacks remained second-class citizens, and most U.S. establishments were still segregated. When the rhetoric finally ended, forty-two years later, an African American was preparing a successful run for the presidency of the United States. Time had certainly passed.

M

ORE

T

ALK

There was talk of a memorial in the

Wichita Eagle

two days after the crash. A decade later, in 1975, people were still talking. On the twentieth anniversary in 1985, people were still talking. And another ten years after that, people were still talking about the absence of a memorial. Frustration and separation between the races were perpetuated in the Wichita community as years passed, with no activity or efforts made by the city to create a memorial. Ron Thomas, who witnessed the crash, explained in a 1996 interview the general feeling of isolation and separation after the KC-135 fell in Wichita's black community:

It seems to me the city did not show much remorse, or enough remorse, outside of the black community. After the crash, and maybe because of the responses of whites, a lot of people in the black community really closed up. It became a black/white thing. People asked, “Why did all those people die here?” and the city never even put up a memorial or anything to acknowledge the loss of life

.

405

Others in the community suggested possible reasons for this: “I think that because of where it was,” said Brenda Gray, a longtime Wichita resident, “it was definitely not so important to the rest of Wichita.”

406

The lingering silence and stagnation after such a tragedy had insidious effects: African Americans felt further excluded from the rest of the community; the crash seemed insignificant, easily forgotten; and the longer it took to do something, the more embedded the perception became. “â¦[I]t would be nice to see some kind of memorial over there,” said a survivor five years after the crash. “It would be a good thing just to have any kind of marker to recognize all those deaths.”

407

They would have to wait. Meanwhile, a seething undercurrent of anger and acrimony boiled just below the surface.