May Contain Nuts (14 page)

Authors: John O'Farrell

Part of me was indignant that one of my children should be a target for bullies

and

need so much help with his school

project. I mean, that wasn't fair â surely the deal was that if your child was victimized in the playground at least there was the consolation that he sailed through all his A levels at the age of thirteen. But the strongest sensation was anger, the primitive fury of the mother wanting to protect her young. Because I didn't just want to frighten off Danny Shea, I wanted to really hurt him. I wanted to pull his hair back until he cried, I wanted to grab him by the throat and shout in his face to never touch my son again, I wanted to make him so frightened of Jamie Chaplin that he would hide behind the piano while Mrs Soames was playing âWhen I'm Sixty-four' rather than so much as brush past him.

Deep down, of course, I knew that it wasn't acceptable to take things into my own hands; I knew that these things had to go through the proper channels. OK, I couldn't remember exactly why it would be totally inappropriate to take on a nine-year-old bully on my own, I just knew that it was. It's a bit like assassinating evil dictators; David would patiently explain to me why this is not a viable United Nations policy and I'd finally understand and agree. Then after a couple of days I was back to saying, âBut why didn't they just plant a bomb under Saddam Hussein's car? Why did they have to invade the whole country?'

Jamie begged me not to tell the teachers at school, claiming this would make it worse, and in an attempt to reassure him I foolishly promised I wouldn't. And so I was left feeling totally powerless. Watching him reluctantly traipse into school every morning like a lamb to the slaughter, thinking about him every moment of the day, wondering if it was happening right now, I'd fret the hours away until I'd got him safely home. Then I would anxiously ask how school was that day and he would parrot a neutral âfine' and without wanting to be too

direct I would say, âNo problems of any sort or anything or whatever as it were?' and he would say nothing, instead voluntarily opt to practise his piano and I would know then that something was very amiss. I knew it would have to be tackled head-on eventually. If you don't stand up to a bully when you are young, you will be bullied for the rest of your life. Ffion told me that and I didn't dare disagree with her.

That week I was the victim of Ffion's most direct assault to date. Or perhaps âoffensive' would be a more appropriate word.

Dear All,

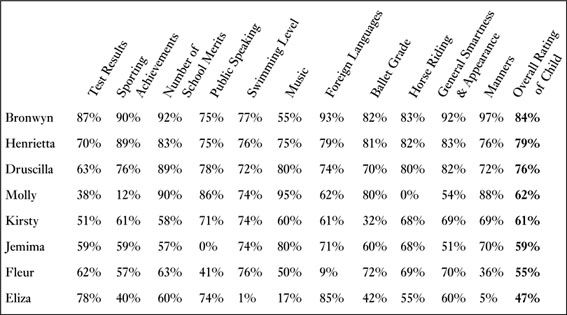

Alice commented that the table that I emailed everyone after the girls' mock exam wasn't fair because it didn't take into account all the other things that the girls do, like Molly's violin etc, which I thought was a fair point!!! So Philip and I have had a bit of fun adding in everything else!!! I think it's interesting to see where their strengths and weaknesses lie!!! Enjoy!!

Ffion.

Attachment: revised league table

I clicked on the little icon and my computer asked me if I was sure I wanted to open this attachment, which was probably quite a wise question. The first thing that struck me about the document that popped up on my screen was how complex it was, how much work this elaborate new league table must have involved. No, that's not true, the first thing I noticed was Molly's position on the list. Just as a seal can hear its own pup on a beach of thousands, a mother can instantly spot her own child's name on a whole page of text. Molly was fourth. The

only girl to reach grade 5 at violin and she was still only fourth. But Ffion had taken all sorts of other attributes and achievements into account and my daughter's musical supremacy had been qualified by shortcomings in other areas, from âsporting achievements' to âballet grade' and, rather incredibly, âmanners'. And looking at the public-speaking scores, I thought Ffion might have made a little more allowance for Jemima's stutter.

So where had Ffion and Philip's complex system for grading all these children left their own daughter? Where in a league table of eight girls could Bronwyn possibly have ended up? Ooooh, there she is, look, right at the top, well done, Bronwyn, what a clever girl! It was there on the computer screen. Who could possibly argue with Ffion that her child was the best when her specially created computer spreadsheet had proved it?

Looking more closely at the scores I saw exactly how she

had contrived to persuade the computer to make her daughter champion. Bronwyn got 83 per cent for horse riding, for example, whereas Molly, who did not ride, scored 0 per cent. âWell that's just ridiculous!' I said out loud; this is all complete nonsense. Then for sporting achievements I noticed that Molly had scored a dismal 12 per cent and my heart sank on recognizing this bitter truth about my precious darling daughter. In fact, 12 per cent was probably generous. She wouldn't catch a ball in twelve attempts out of a hundred because she was terrified of them. If anyone so much as tossed a little beanbag at her she would duck and cower in fear. âWorse than an England cricketer,' as David had said.

However, I was gratified to see that Molly had merited an excellent 88 per cent for manners, second only to Bronwyn's 97 per cent. Eliza Rhys-Jones managed 5 per cent for manners. Yes, well, that was probably about right, I thought to myself. In fact, looking at all the grades in more detail, I had to concede that many of them were pretty fair assessments of the children concerned, with the exception of Bronwyn's scores, which were patently much too high, and Molly's, which were much, much too low. I mean, fourth out of eight, it was so insulting! The more I stared at it, the more incredulous and indignant I became. And Ffion's emails had a really annoying habit of using exclamation marks to sugar an outrageous message. I suppose the next stage would be for us to start using those smiley-faced emoticons that our kids put on the end of their messages, in the hope that we could get away with being even ruder:

get stuffed ffion you fat cow :)

or

drop dead yourself alice, you anorexic flat-chested bitch ; -)

This file had been sent to every parent on the email list on Ffion's computer, nearly every parent I knew would see that Molly had only scored 54 per cent for âgeneral smartness and

appearance'. (Although I noticed that Eliza's parents, whose dreadful daughter was bottom, were wisely omitted from the list of recipients.) It was insulting nonsense, it was preposterous, and yet I knew some less judicious mothers might take it seriously. Where was the A+ for Molly's Mother's Day poem entitled âMy Mother' that I kept in my handbag? And she had given her own daughter 55 per cent for music, which was way too high. (Bronwyn was being taught the piano; they were using the Suzuki method. On a Yahama keyboard. And she sounded like a knackered old Kawasaki.)

Examining the league table in more detail, I wondered what would happen if you discounted the rather arbitrary criterion of horse riding. Using David's calculator, I discovered that if you took out the stipulation of being expected to be able to ride a horse in London in the twenty-first century, Molly would move up the table two places, so really you could say she should have finished second. Second out of eight was pretty impressive, though if you deducted 15 per cent from Bronwyn's score for âmanners' for that time she asked me if we couldn't afford an au pair, then Molly would have been top.

And at least Molly didn't go round to other people's houses and then neglect to flush the toilet after doing number twos, like Bronwyn, but I didn't see âability to flush toilet after doing a poo' listed among Ffion's criteria. No, I mustn't resent little Bronwyn, I thought to myself, even if I had wanted to buy her a âlack-of-charm' bracelet for her last birthday; she's one of Molly's best friends and she's not to blame for her over-competitive mother. Even if she did cheat in the school's egg-and-spoon race. No penalty for that on the league table, I noticed; no points deducted for the tell-tale traces of Blu-tack discovered on the winner's teaspoon. The whole thing was farcical. It showed how pitiable Ffion now was, how pathetic

and insecure a mother she had become. And then when David finally came in late that night to find me sitting up in bed popping bubble wrap: âDavid,' I asked, âdo you think that Molly should maybe start riding lessons?'

When I moaned about Ffion to David he always asked me why I remained friends with her, but you can't just cancel a friendship like a monthly direct debit. Come to think of it, I never got round to cancelling my direct debits either. I think I was still paying for membership of a gym I had only ever visited twice in January 2003. Lasting friendships are forged when people are thrown together under extreme duress: comrades in the trenches, cell-mates in prison or middle-class new mothers reeling in shock from giving up careers to be kept awake and puked on for twenty-four hours a day. Once you have shared the hell that was the Mothers and Babies Aqua-aerobics, you feel a profound bond that is hard to break. Both my parents had died before I became a mother and so I had been desperate for some support during those early days. And we had kept finding we had new things in common. When to my shock and amazement my baby daughter started growing teeth, it turned out that Ffion and Sarah's children were growing teeth as well. When she turned five, their children turned five as well; it was uncanny.

But on a deeper level I think I didn't want to give up on Ffion because I didn't want to

lose

. I was scared of dropping out of the race. Besides, the last mums to disappear from our group had given us someone new to badmouth for years after. It's human nature â as soon as someone walks out of the room you want to bitch about them. I'm sure it was the same in that Antarctic snowstorm when the frostbitten Captain Oates staggered out to die in the blizzard rather than be a burden to his comrades: âI'm just going out. I may be some time.' A very

brief pause and then, âThat bloody Oates, he's so bloody worthy, isn't he?' âGod, yeah, what a martyr,

oh don't worry about me, leave me to die, blah, blah, blah

⦠I'm glad to see the back of him quite frankly.'

So every time Ffion won a battle like this it made me all the more determined to win the war. Molly's entrance examination to Chelsea College required me to pass two tests. But while I had practised countless mock exams, not once had I actually attempted a dummy run in the more difficult of the two tasks. Not once had I gone out there in disguise and seen what sort of reaction I got as I tried to pass myself off as a girl about to leave junior school.

âYouth club?' said David in astonishment. âWhat if one of Molly's friends is there?'

âWe'll go somewhere else, somewhere miles from here.'

âBut, then, how do we find one? I mean, where do we â¦'

âWe make a few calls. Honestly, David, you're supposed to be the adult here â¦'

Since he'd had the idea that I disguise myself as âOdd-kid', I had felt the need to reclaim the initiative on this project, and so I made the most of the fact that he was struggling to keep up with the next part of the plan. A vicar in Putney said that our daughter would be more than welcome to come along to their youth club on Friday evening, and promised to tell the young chap who ran the club to look out for her. âWhereabouts in Putney do you live?' he asked David. âEr, just about to move in â¦' improvised David, rather impressively I thought, though I didn't say so. âAnd we thought it would be nice for Molly to come along to the youth club so that she'd know a few children before she arrived ⦠Yes, that's it.'

âSuper. So which road are you moving into?'

There was a pause.

âSorry. You're breaking up â¦' said David, his hand half covering the mouthpiece. âI'm on a mobile and we're just going into a tunnel â¦' he croaked, casually twiddling the flex on his office phone before placing his finger over the button to cut off the call.

I sat in the back as we drove west. We had left early, before the kids were picked up from school by our babysitter so that our children wouldn't be permanently scarred by the vision of their mother wearing geeky kids' clothes and a baseball cap with spots all over her face. David thought I had rather overdone it on the acne, but I maintained that it had to make people look away, this had to be a ârude-to-stare' face; that come D-Day, the decoy explosions on my skin had to be sufficiently alarming to distract the lookouts from spying on the secret infiltrator slipping behind enemy lines.

We were so early that we went for something to eat. I'd never allowed the children to go to McDonald's, but now it just felt right, and in any case it was nice to be somewhere where the staff had worse spots than I did. I asked for a Happy Meal. In all the acting that I was going to have to do, surely nothing would be as demanding as pretending to relish every bite of that disgusting burger.

âFinish your chips, Alice.'

âIt's Molly,' I hissed. âMy name is Molly,

Dad

. And they're called “fries” â¦'