Mattie Mitchell (9 page)

Authors: Gary Collins

Very pleased with his find, he didn't consider stealing them

wrong. The knives had been left unguarded. He had simply taken

them. He would fully expect the same done to him, if he were

foolish enough to leave such valuables unattended.

Buka now turned his attention to the pungent codfish. Peering

at it in the darkness, he tore a strip from its thick breast and pushed

a piece of it into his mouth. For a second he was puzzled, then

revolted, as an unexpected taste exploded in his mouth. Spewing

the fish out of his mouth, he retched again and again, trying to rid

his mouth of the putrid taste. Reaching to the ground he pulled

several leaves from the bushes. He crushed them in his hands,

stuffed the leaves into his mouth, and chewed them into a pulp

before spitting the entire contents away, sluicing most of the foul-tasting fish with it. He flung the fish away into the night, where it

fell with a soft thud among the bushes.

What manner of creatures were these men with the white

skin, who would catch so many of the sweet-tasting

bobusowet

only to spoil them all with their cruel-tasting sand? Several times

he hawked the salty bile out of his throat, and still the bittersweet

salt residue remained, assailing his sensitive taste buds.

Only when he had recovered from the shock of the experience,

and had rinsed and cleansed his mouth several times by drinking

from a small stream, did he recognize the taste that had invaded

his mouth. It was the taste of sea water, only many times greater.

But why the strangers had used it on the fish, or where it had

come from, mystified him.

Leaving the wooded shoreline behind and climbing the slope

in the darkness, he was soon away from the coast and the threat

of being discovered. He crawled underneath the overhanging

branches of a huge she-spruce and, squirming around a few times,

soon fashioned a rough bed for himself on the hard ground. He

spat the last of the tainted fish taste out of his mouth, surprised

that the sensation still remained. And without a thought to any

further comfort, and smiling at the feel of the new knives he had

taken, he lay down upon the earth and went instantly to sleep.

SILENCE GREETED MATTIE WHEN

he finished his tale. The

children stared at him in wonder, their mouths agape. They all

wanted to hear more about Buka the Red Indian warrior. But

Mattie told them, “You mus' listen ver' many times to one story.

When you kin tell it same way to someone else, den you ready to

'ear more 'bout Buka the true Red Indian.”

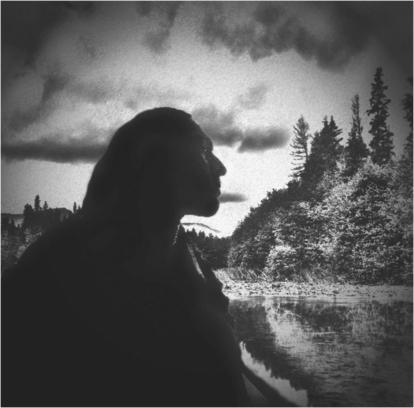

“Mattie came down out of the hills

bringing dark on his shoulder.”

ILLUSTRATION BY CLINT COLLINS

CHAPTERÂ 7

ELWOOD WORCESTER WAS BORN IN

Massillon, Ohio, on May

16, 1862. As a young man working in a dingy, cramped railway

office after the death of his father left his family in poverty, he

had what for him was a life-changing experience. One day his

dark office was suddenly filled with a brilliant unnatural light.

From somewhere beyond the steady, surreal gleam of light, a

strong but very clear, soft voice said, “Be faithful to me and I

will be faithful to you.”

After that he became an ordained Episcopalian minister. He

was the founder of the Emmanuel Movement of America, whose

philosophy attributed physical, mental, and nervous problems

as well as psychotherapy with the spiritual well-being of the

human mind. Worcester founded the Boston Society for Psychic

Research. His activities played a major role in helping with

research for the dreaded disease tuberculosis.

But Worcester was something more. He was an avid

sportsman. He went to great lengths and took advantage of every

opportunity to experience the wonders of hunting and fishing

all over North America. He regarded it as “one of my choice

blessings that these pleasures have never palled on me.” The

preacher would think nothing of walking the great distance along

a terrible trail to Irondequoit Bay, in Lake Ontario, just to fish for

a few yellow perch, several black bass, or even sunfish.

Having heard about the wonders of northern Canada and the

largely unexplored regions of that vast country, he decided to

go there. Worcester obtained rail passage to Quebec, where he

arranged for four native Indians, who spoke no English and knew

only a few words of the French language, to take him into the

interior.

They left Lac-Saint-Jean, headwaters of the mighty Saguenay

River, and made their laborious way north by canoe into the

lonely, uninhabited wilderness of Quebec. Weeks later and several

hundred miles away from any human habitation, Worcester had

finally experienced enough of the north wilds. Blaming the

whole unpleasant ordeal on his “four ignorant Indian guides,”

he returned to the modern world vowing never to use Indians as

guides again. Then he met Mattie Mitchell.

ANOTHER OF WORCESTER

'

S PASSIONS

was reading, when

he could find the time. He especially loved browsing through

historical accounts about Canada, partly because of its self-proclaimed status as a sportsman's paradise, and partly due to his

recent disappointing foray into that north land.

What he found one day, while reading a historical work in the

city of Philadelphia, was a riveting account of another northern

countryâNewfoundland. He relished the writings of John and

Sebastian Cabot. The descriptions the two men had given about

their “discovery” of the island of Newfoundland fascinated

him. The Cabots had found scores of fishes “great and small.”

Vast shoals of cod were taken from the virgin blue sea as easily

as dipping them up with a simple basket. Silvery salmon and

gleaming trout they scooped from the shallow rivers. They salted

down barrels of the protein-rich fish.

Foraging upon the unspoiled land, Cabot's men with their

long-barrelled muskets brought back the carcasses of tender

caribou and excited tales of “numberless fleet footed Deeres.”

Their flesh too was salted for transport across the ocean. Animal

skins for a fur-hungry England were stowed aboard their ships.

All of these trophies, which were taken back to England, served

as mere samples of what this “New World” had to offer to the

explorers.

But of all the amazing events the Cabots had recounted, one

of them stuck in Worcester's mind above all of the rest. The man

the English called John Cabotâwhose birth name, Giovanni

Caboto, was Italian, and whose only known signature appears as

Zuan Chabottoâgave to Henry VII, the Tudor king of England,

three wondrous pearls. The three pearls had been taken from the

shells of freshwater mollusks pulled from just one of the countless

rivers of that far-off “New Founde Land.”

This revelation, so boldly recorded by these European

adventurers hundreds of years ago, played upon the good

reverend's mind. He was awakened in the middle of one winter's

night by a dream about pearls. He sat upright in his warm

featherbed, and there and then decided to plan a trip north to

Newfoundland the very next spring. As an added bonus, this big

island was the only place left in the world where one could fly-fish Atlantic salmon freely.

Tales of caribou with antler points by the dozens, huge,

shiny black bears unequalled anywhere could be hunted there.

Worcester couldn't wait for the winter to pass. This time, though,

he would not allow Indians to guide him, if there were any on that

island in the sea.

Worcester arrived on Newfoundland's coal-burning ferry boat

in early June and decided he would need a sturdy schooner for

his coastal explorations of the river mouths. In the rugged outport

town of Port aux Basques, where the ferry docked, he was told

there wasn't a schooner for sale. However, one of the fishermen

knew of a “right smart scunner fer sale in Bay of Islands,” a deep

fjord farther north along the island's west coast.

It took him several days of walking and hitching boat rides

with the friendly fishermen before he arrived in the Bay of

Islands. Worcester was enchanted by the rawness of the place. It

seemed like the entrance to every cove gave a more spectacular

vista than the one before it: massive fjords, their many valleys

and gorges filled with the lush green of virgin forests; waterfalls

that fell from great heights, with silvery mists marking their fall

below the treed skyline; high, flat-topped mountains came down

to the sea edge; green canyons twisting around the mountain

bases beckoned a man into their realms.

And all of it largely unexplored.

The young, ruddy-faced fisherman back in Port aux Basques

who had told him about the schooner had not lied. The vessel was

still available. Its owner was now unable to fish for a living.

Frank was a man in his mid-fifties, but his weathered face

made him look much older. The man frequently coughed, and

walked with a knotty wooden cane. Both men walked out over a

large wharf to which the schooner was securely tied fore and aft

with heavy manila lines.

A bright, hand-painted board with the name

Danny Boy

was

attached to the vessel's stern below her low taffrail. The tide

was out, and Worcester knew the schooner was his as soon as he

looked down on her neat, spotless single deck, with small double

doors in her forecastle swung wide to allow the warm sun into

the dark cabin.

Without climbing aboard, although the schooner's owner had

invited him to do just that, Worcester wanted to know the asking

price. The man leaned heavily on the cane cut by his own hand,

started to speak, and went into a spasm of coughing. He quickly

recovered, spat a grey ball of phlegm down into the harbour

water, and answered this way:

“I cut every stick out of the hills behind ye. Me boy was still

in school then, but he helped with what he could, I will give him

dat. Danny, his name is, but we all the time calls him Danny

B'y. So we called the scunner after our b'y.” His voice seemed to

weaken a bit at the mention of his son. Then he continued.

“Mucked the logs and crooked timbers fer her frame on me

back and hand slide alike, in its turn. Chopped the timbers meself,

I did, and nailed every plank from garbit to gunnel, rammed her

tight as a drum wit' oakum I spun wid me own two hands. 'Er

decks are poured with heavy pitch too, dey isânot that cheap,

runny tar that sticks to a man's rubbers on hot days and always

laiks.”

Here Frank turned away and coughed again before continuing.

Worcester was fascinated with the man's language. His rapid

conversation was aided with arm and hand gestures just as

quick. He pointed toward the forested hills, the long blue bay,

the harbour, or the newly painted schooner as his talk warranted.

Frank's chest-heaving cough produced another pearl-grey

issue that he again spat over the wharf edge. Worcester thought

he noticed flecks of blood mixed with the sputum as the man

cleared his throat and continued his conversation as though he

had not stopped.

“I wuz askin' $1,900Â fer 'er, sir, but she was just launched

fer dis year's fishin' and she'll laik a wee bit at first. 'Twill tek a

few days fer 'er seams to plim up. She'll laik nar drop after dat.

So I'm askin' $1,850, to 'low fer dat inconvenience every spring

to the man wot buys 'er. I won't change me mind on that price,

though, sir. Dat's me final one. An' I feels right sure I won't be

gyppin' a man wit' it.”

Worcester smiled at the man's honestyâwhen he finally

figured out what he had said. When Frank explained what “plim”

meant, he willingly agreed to the price.

“Cash on the barrelhead,” cautioned the wily old fisherman.

When Worcester asked if there were any papers to sign, he

replied, “A man's 'and on it is good nuff fer me, sir.” Spitting into

his right palm, he offered it to the American, who very reluctantly

shook itâremembering the spittingâsealing the deal.

Worcester was now the proud owner of a handcrafted, thirty-nine-foot, seaworthy schooner. She was supposed to be forty feet

long, Frank told him, but, “Da stem piece I cut 'ad a bit too much

rake to it fer me likin', so I shartened 'er keel a bit.”

Worcester decided not to ask what it all meant. Counting out

the American bills, he told a beaming Frank he loved the boat just

as she was and that he would move his gear aboard the

Danny

Boy

immediately.

While Frank counted out the most money he had ever held in

his handâafter being assured the odd-looking bills were not only

good but worth more than the island's currency, something he did

not understandâWorcester asked him where he could obtain the

services of a good local guide. He wanted someone who not only

knew about hunting but also someone who knew the rivers well.

Worcester never brought up his intention to search for freshwater

clams.

Frank looked up from his money and replied without

hesitation. “Mattie Mitchell is the man fer you, sir. He is an Injun

man but as good as ar white man, better dan some of da ones I

knows about.”

Remembering his experience with the Quebec Indians,

Worcester replied, “There must be a few white hunters and

trappers around these parts that could show me around this

country. I will need such a man for a few weeks and I will pay

him, of course.”

“Dere are some as you say, sir, right smart hunters and good

at trappin', too, fer dat matter. But Mattie is still your man, sir.”

And again gesticulating with his skinny arms, he went on. “I does

some huntin' and a bit of trappin' too in the fall time. Dat's after

me voyage of fish 'as been made and shipped away, ya know. An'

I knows the hills pretty good meself.” Here Frank threw his arms

wide, indicating the surrounding green mountains.

“But Mattie, sir, is a long cut above me er anyone else dat I

knows of in dat regard. Dis man knows the country like the back

of 'is own 'and an' farther away dan dat. You won't find no one

close to 'e's equals anywhere on dis coast, er any other one on dis

island, sir. I knows him well, sir. Jes' dis marnin' he paddled along

be me wharf in dat old canoe of 'is, on his way out the bay. Won't

be gone more dan two days, I figure. Didn't have no gear aboard

dat I could see. Don't talk much, Mattie don'tânot like me, eh?”

Here Frank smiled, showing strong, tobacco-stained teeth.

For the next two days, Worcester explored the village. He met

almost all of the friendly men, a few of the women, and several of

the children who followed the 'Merican man around.