Masterpiece (2 page)

Authors: Elise Broach

Uncle Albert nodded vigorously and beckoned to Marvin. “Marvin, my boy, what do you say? You’ll have to go down the bathroom pipe and find that contact lens. Think you can handle it?”

Marvin hesitated. Mama and Papa were still arguing. Now Papa looked at him unhappily. “I’d go myself, son—you know I would—if I could swim.”

“No one can swim like Marvin,” Elaine declared. “But even Marvin may not be able to swim well enough. There’s probably a lot of water in that pipe by now. Who knows

how far down he’ll have to go?” She paused dramatically. “Maybe he’ll never make it back up to the surface.”

“Hush, Elaine,” said Uncle Albert.

Marvin grabbed the fragment of peanut shell that he used as a float when he swam in his own pool at home. He took a deep breath.

“I can try, at least,” he said to his parents. “I’ll be careful.”

“Then I’m going with you,” Mama decided, “to make sure you aren’t foolhardy. And if it looks the least bit dangerous, we won’t risk it.”

And so they set off for the Pompadays’ bathroom, with Uncle Albert leading the way. Marvin followed close behind his mother, the peanut shell tucked awkwardly under one of his legs.

I

t took them a fair bit of time to reach the bathroom. First they had to crawl out of the cupboard into the bright morning light of the Pompadays’ kitchen. There, baby William was banging on his high chair with a spoon, scattering Cheerios all over the floor. Ordinarily, the beetles might have waited in the shadows to snatch one and carry it off for lunch, but today there were more important tasks ahead. They scuttled along the baseboard to the living room, and then began the exhausting journey over the Oriental rug, which at least was dark blue, so they didn’t have to worry about being seen.

All the way to the bathroom, Marvin could hear Mr. and Mrs. Pompaday yelling at each other.

“I don’t understand why you can’t just take the pipe apart and find it,” Mrs. Pompaday complained. “That’s what Karl would have done.” Karl was Mrs. Pompaday’s first husband.

“

You

take the pipe apart and find it. And flood the

bathroom. Then we’ll have to replace more than your contact lens,” Mr. Pompaday fumed. He stomped to the phone. “I’m calling a plumber.”

“Oh, fine,” said Mrs. Pompaday. “He’ll take all day to get here. I have to leave for work in twenty minutes, and I won’t be able to find my way to the door without my contact lenses.”

James, Mrs. Pompaday’s son from her first marriage, stood in the doorway. He was ten years old, a thin boy with big feet, serious gray eyes, and a scattering of freckles across his cheeks. He would be eleven tomorrow, and Marvin and his family had been trying to think of something nice to do for his birthday, since they infinitely preferred him to the rest of the Pompaday family. He was quiet and reasonable, unlikely to make sudden movements or raise his voice.

Seeing him now, Marvin remembered how James

had caught sight of him once, a few weeks ago, when Marvin was dragging home an M&M he’d found for the family dessert. Marvin had been so excited about his good luck that he’d forgotten to stay close to the baseboard. There he was, out in the open sea of cream-colored tile in the kitchen, when James’s blue sneaker stopped alongside him. Marvin panicked, dropped the M&M, and ran for his life. But James only crouched down and watched him, never saying a word.

Marvin hadn’t told his parents about that particular close call. He’d vowed to himself that he’d be more careful in the future.

Now James shifted thoughtfully on those same blue sneakers. “You could wear your glasses, Mom,” he said.

“Oh, fine,” said Mrs. Pompaday. “Wear my glasses. Fine. I guess it doesn’t matter what I look like when I meet clients. Maybe I should just go to work in my bathrobe.”

By this time, Uncle Albert, Marvin, and his mother had reached the door of the bedroom, and the bathroom lay just beyond. Unfortunately, the three humans were effectively blocking the route. Three jittery pairs of feet—one in sneakers, one in high heels, and one in loafers—made it hard to find a safe path.

“Stay close to me,” Mama told Marvin. She hurried along the door frame. Dodging the spikes of Mrs. Pompaday’s heels, Marvin and Uncle Albert followed.

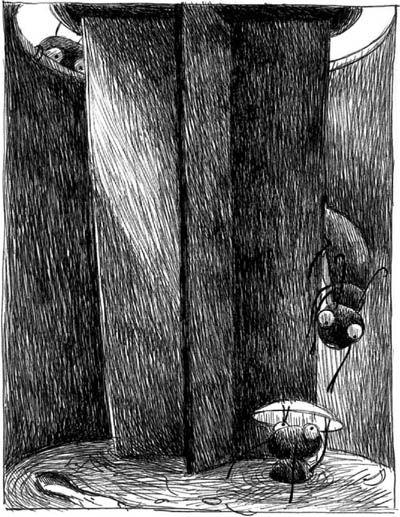

They made it up the bathroom wall to the sink without mishap. Normally, the light tile would have made them easy targets for a rolled-up newspaper or the

bottom of a slipper. But the Pompadays were so engrossed in their argument that they didn’t notice three shiny black beetles scrambling onto the sink.

“I’ll keep a lookout,” Uncle Albert said. “You two go ahead.”

Marvin and his mother tumbled and slid down the smooth side of the sink to the drain. They ducked under the silver stopper and stood on the edge of the open pipe, staring into blackness.

Marvin could hear a distant trickling sound. As his eyes adjusted, he saw water, murky and uninviting, a few inches below. He thought of Cousin Elaine’s grim prediction and shuddered. Why hadn’t his mother taken a firmer stand against this?

“Well . . . here I go,” he said to Mama, who promptly grabbed his leg and held fast.

“Now don’t do anything rash, darling,” she told him. “Go slowly, and come right back to me if it seems dangerous.”

“Okay,” Marvin promised. He clutched his peanut-shell float and took a deep breath. Then he launched himself into the void.

He barely remembered to shut his eyes before the cold water closed over his head. Pedaling his legs frantically, he came bobbing back up to the surface. The cloudy water tasted vaguely of toothpaste. It smelled horrible.

“Marvin? Marvin, are you all right?” Mama’s voice echoed thinly in the pipe.

“I’m fine,” he called back.

He swam through the scummy water, which was littered with every nasty thing that might wash down a human’s drain: bits of food, hair, slivers of soap. He wanted to throw up.

“Do you see it yet?” his mother called.

“No,” Marvin answered. He suddenly realized he had no idea what a contact lens looked like.

Then, as he was about to turn back, he

did

see something: a thin plastic disc, stuck to the side of the pipe. It looked just like the fruit bowl Mama used at home. Out of breath, he shot back up to the surface.

“I found it, Mama!” he yelled.

“Oh, good, darling.” His mother breathed a sigh of relief. “Now we’d better hurry, before someone turns on the faucet and washes us both away.”

Marvin discovered he couldn’t hold on to the contact lens and the peanut shell at the same time. Reluctantly, he let go of his float, took a deep breath, and plunged under the water again.

In the distance, he heard his mother cry, “Marvin! Your float!” But he moved his legs swiftly, unburdened by the peanut shell, and glided down through the dark water. He swam straight to the contact lens and clasped it with his front two legs. Pulling it away from the side of the pipe, he shot quickly back to the surface. Through the lens, he could see his mother, wavy and distorted, looming above him. She’d crawled down the side of the pipe to the water’s edge, beckoning to him.

“Oh, Marvin, thank heavens. You are a wonder, darling. What leg control. I wish my old ballet crowd could see you.” She took the lens from him. “Whew! The water smells positively vile. And what a fuss over this little thing! Why, it looks exactly like my fruit bowl.”

Holding it gingerly on her back, Mama crawled up the pipe. She scooted under the stopper, with Marvin

close behind her, and together they dragged the lens up the side of the sink.

Uncle Albert rushed down to meet them. “By George, you’ve done it!” he cried. “Marvin, my boy, you’re a hero! A hero! Wait till I tell your aunt Edith!”

Marvin beamed modestly. He flexed his legs and shook them dry.

“Let’s see, where shall we put it?” Mama asked.

They looked around. “By the faucet, maybe,” Marvin suggested. “That way, it won’t get washed down the drain again.”

They placed the lens near the hot-water handle and dashed behind a green water glass just as James walked into the bathroom.

“After all this trouble, they’d better find it,” Mama whispered grimly. Marvin kept his eyes on the contact lens. It glistened in the morning light, a faint blue color.

They could hear Mr. Pompaday on the phone with the plumber. “What’s that? Oh, okay, I’ll look.” He bellowed, “James! Are you in the bathroom? Make yourself useful. Are the pipes in there copper or galvanized steel?”

James stood at the sink. “I don’t know,” he said. “But, Mom, I found your contact lens. It’s right here by the faucet.”

And then what a commotion: Mrs. Pompaday rushing into the bathroom in disbelief, Mr. Pompaday loudly

apologizing to the plumber, and James lifting the contact lens in his outstretched palm.

“Well, I guess that’s that,” Mama said to Marvin as soon as the bathroom emptied. “We’d better head back and let your father know you’re all right.”

So Mama, Uncle Albert, and Marvin ambled home, where everyone greeted them joyfully. Papa, Aunt Edith, and Elaine all patted Marvin on his shell, but nobody wanted to hug him. He was wet and slimy, and smelled overpoweringly of the drain water.

“I think I need a bath,” Marvin said.

And then Mama and Papa fussed over him, filling the bottle cap with warm water and adding a single grain of turquoise dishwashing detergent. Marvin sank into the bubbles and floated in the pool to his heart’s content, until he was shiny and clean again.