Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume 2 (121 page)

Read Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume 2 Online

Authors: Julia Child

CHAPTER FIVE

Charcuterie: Sausages, Salted Pork and Goose, Pâtés and Terrines

T

HE FOUNDATION AND MAINSTAY

of French

charcuterie

is pork in all its forms, from sausages and stuffings to hams,

pâtés,

and

terrines. Chair cuite,

meaning meat that is cooked, was obviously the derivation of this marvelous keystone of French civilization, but modern

charcuterie

shops, like American delicatessens, have branched out and sell all manner of edibles, such as aspics and ready-to-heat

escargots,

heat-and-serve lobster dishes, ready-made salads, mayonnaise, relishes, canned goods, fine wines, and liqueurs. In the best establishments, all the cooking is done on the premises; they cure their own hams, make their own salt pork and fresh and smoked sausages, have their own formulas for their beautiful display of

pâtés.

Let us all pray that this delicious way of life will long remain, because there are few things more satisfying to the soul than the look and smell of a French

charcuterie.

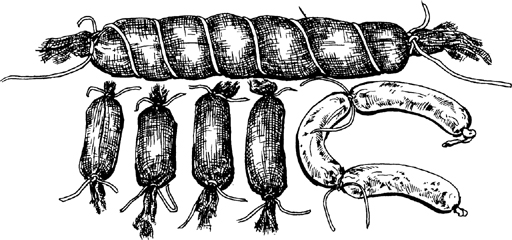

SAUSAGES

Saucisses et Saucissons

With the virtual disappearance of European-style neighborhood

charcuteries

in this country, it behooves every serious cook to have a few sausage formulas on hand for such delicious concoctions as

saucisson en croûte, saucisson en brioche, saucisson chaud et pommes à l’huile

—that wonderfully simple dish of hot, sliced sausages and potato salad—little pork sausages for breakfast and

garnitures, and those lovely white-meat sausages with truffles,

boudins blancs.

A sausage is only ground meat and seasonings, a mixture no more complicated than a meat loaf, and for fresh unsmoked sausages you need no special equipment at all. An electric meat grinder and a heavy-duty mixer will make things easier, but a sausage-stuffing mechanism and sausage casings are not necessary because you can use other means to arrive at the sausage shape. In French terminology a

saucisse

is primarily a small and thin sausage, usually fresh, and a

saucisson

is a large sausage usually smoked or otherwise cured; the one may be called the other, however, if it is a question of size. Here are directions for forming them in casings and a practical substitute for casings, as well as a short discussion on caul fat.

SAUSAGE CASINGS

Natural sausage casings, the flexible, tubular membrane that holds the sausage together and forms its skin, are made from the thoroughly scraped and cleaned intestines of hogs, cattle, and sheep, of the stomachs of hogs, and of the bladders of all three. Sheep casings are the most valuable and expensive of all, and also the most fragile; varying in diameter from ⅝ to 1 inch, they are used mostly for fresh pork breakfast sausages and the small cocktail or garnishing sausages called

chipolatas. Beef casings are for large sausages like bolognas, salamis, and blood sausages, and middle sizes like cervelats and mettwursts. Hog casings come in various lengths and widths: bungs (

gros boyaux

), or the

large intestine; hog middles (

fuseaux

), or the middle intestines; small casings (

les menus

), which are the small intestine.

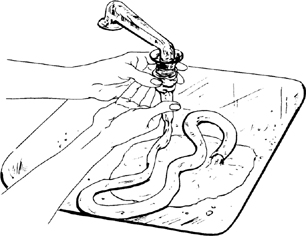

The most practical and easily obtainable for the home sausage stuffer are small hog casings, the kind your butcher uses to make his fresh pork sausages or fresh Italian sausages. If he cannot supply you with a few pieces, he can order them for you; or look up in the classified telephone directory under Sausage Casings or Butcher’s Supplies. Ask for a set of small hog casings, medium width. You will get a bundle of 16 to 18 casings, each 20 feet long, which are twisted into a complicated swirl resembling wet spaghetti. To disentangle the pieces, unwind the set on a very large table. Then start with one piece from the middle and gently pull it through the maze, first on one side, then on the other. Disentangle all the pieces, winding each up on your fingers as you do so, like string. Pack the pieces between layers of coarse salt in a large screw-top jar and store in the refrigerator. They will keep safely for years as long as they are well covered with salt.

Before using a piece of casing, wash it off in cold water, then soak for one but not more than two hours in cold water. Any casing you do not use may be thoroughly rinsed inside and out, wound up again, and repacked with salt in your casing container.

How to use sausage casing

Casing is ideal for sausages because it holds the meat in perfect symmetry; the problem is finding a way to get the meat into these marvelous containers. Professionals use a stuffing machine,

poussoir,

which is a large cylinder with a pushing plate at one end and a nozzle at the other: the meat goes into the cylinder, the casing is slid up the outside of the nozzle, and a crank operates the plate, pushing the meat from the cylinder through the nozzle and into the casing, which slowly and evenly fills with meat as it slides off the nozzle. There are home models available from some butcher supply houses and mail-order sources; anyone going into serious sausage making should certainly have one, since alternatives can only be makeshift and more or less successful depending on your sausage mixture. Here are the alternatives, including hand stuffer, meat grinder, and pastry bag. You will work out your own system.

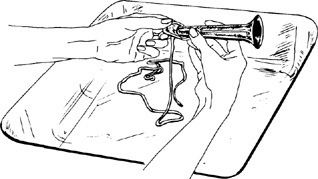

Whichever of the three methods you choose, you will need a nozzle of some sort onto the outside of which you slide the sausage casing. This can be a funnel, the metal tube that fits a professional-size pastry bag, or a regular sausage stuffing nozzle; whatever it is, we shall call it by its official name, stuffing horn. After the sausage casing has soaked for an hour in cold water, cut it into 2- to 3-foot lengths so it will be easy to deal with.

Wet horn in cold water; |

|

| Hold the large end of the horn under a slowly running faucet of cold water, and push casing up outside with your fingers, being careful not to tear casing with your fingernails. |